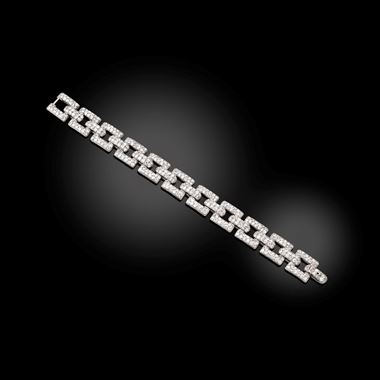

The wide articulated strap of lattice design, composed of domed lozenge-shaped gold links and brilliant-cut diamonds.

As one might guess from the name ‘Van Cleef & Arpels’, the famed jewellers was a union of two families, joined through marriage in 1895. On one side was Alfred Van Cleef, the son of a lapidary based in Amsterdam, and on the other was Estelle Arpels, whose family were dealers of precious stones. The following year, Van Cleef went into business with his father in law Salomon Arpels, and the family firm was born.

After operating for several years from an office on the first floor of 34 Rue Drouot, the partners eventually opened a boutique in 1906 on the fashionable Place Vendôme, which benefited from a stream of wealthy American and European travellers staying at the nearby Ritz Hotel, and had been a destination for high jewellery since 1893, when the house of Boucheron led the charge by moving into number 26. Around this time, Van Cleef & Arpels (often referred to as VCA) primarily designed jewels in the fashionable, 18th century-influenced, platinum and diamond-dominated ‘Garland’ style popularised by their rivals Cartier, and then gradually moved into the nascent Art Deco style after the First World War. At the 1925 Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes (which would later give its abbreviated name, ‘Art Deco’ to the sharply modern aesthetic it showcased), Van Cleef & Arpels exhibited a selection of jewels that flitted between the simple geometry and fresh colour combinations of their contemporaries and a lush, floral style of their own. A brooch naturalistically modelled as two roses, pavé-set with glittering diamonds and buff-topped rubies and emeralds, flaunted VCA’s ambitious and virtuosic stone setting techniques and won them a Grand Prize.

The following year in 1926, Alfred and Estelle’s daughter Renée Puissant took the reins as the company’s creative director. Working with the designer René Sim Lacaze, the next 20 years of their creative leadership saw VCA develop a repertoire of designs which would come to define their distinctive aesthetic, and become some of the most sought-after jewels in the present day. One of the most significant of these advances was the serti mysterieux (‘mystery setting’) which they developed in 1935. This painstaking technique involved first making a design out of a grid of gold wire, and then gathering vast numbers of perfectly matched stones– a daunting task in itself. Then, they would be faceted in a square step cut, calibrated to tesselate in the intended design, with an extra groove cut beneath the girdle on two sides of each stone. Rubies and sapphires were favoured – emeralds were seldom used as they were too fragile (though a few emerald examples are known). This groove allowed them to be threaded onto the gold wire grid, sliding along and fitting flush against their neighbours on all sides. The effect was a glittering surface of pure colour, the stones set perfectly together without any metal showing at all. While at least two of VCA’s competitors had experimented with this technique, only VCA saw its potential, and further developed it to follow curved surfaces. They started using it as accents for accessories such as cigarette cases and powder compacts, before applying it to simple bombé Boule rings. As their serti mysterieux designs became more amibitious, some of the firm’s most important clients began to take notice, such as the Duchess of Windsor, who had a double holly leaf brooch in diamonds and rubies en serti mysterieux, as well as a pair of ivy leaf ear clips to match her ruby and diamond necklace from Cartier (which she later had completely reimagined by René Sim Lacaze).

Other jewels from this golden age under Puissant and Lacaze included Ludo (1934) an updated take on the garter bracelet, the strap consisting of hexagonal or brick-shaped links in yellow gold with a variety of bold, geometric clasps, and Passepartout (1938), a suite of transformable floral jewels set with bright combinations of sapphires and rubies, designed to be adapted to a variety of different uses. Similarly versatile were the ogee-curved Flamme brooches (1934), which could be worn alone or in combination, pinned on the clothes or worn in the hair, and the Minaudière, named after Estelle Arpels for her habit of deliberately acting coy (‘minauder’ in French) – an upsized and more useful vanity case which included compartments in various combinations for powder, lipstick, cigarettes, coins and occasionally a watch. Inspired by a request from the Duchess of Windsor to fit the zipper of one of her dresses with a diamond clasp, Puissant and Lacaze were inspired to create the Zip necklace, designed as a common clothes zipper entirely in gold and precious stones, which was finally realised to great acclaim in 1951.

The firm cast a wider net by expanding from its native France, opening a branch in New York in 1939. A series of ballerina brooches were dreamed up soon afterwards by their New York-based designer Maurice Duvalet and jewellery John Rubel while watching a Flamenco performance, which led to various dance and fairy-inspired jewels set with rose diamonds, including one designed as ‘the Spirit of Beauty’, purchased by the socialite and Woolworth heiress Barbara Hutton.

With this range of imaginative and eclectic jewels, VCA attracted a particularly enviable clientele – aside from the Duke and Duchess of Windsor, the firm also counted the collectors Lady Deterding, Lady Granard and Daisy Fellows among the many fashionable figures who sported their designs. VCA secured a number of prestigious commissions, including a superb diamond tiara and necklace for Queen Nazli of Egypt and a tiara for Princess Fawzia, as well as supplying and remounting a number of lavish jewels for the Maharajah of Baroda and the Shah of Iran. They were the favoured jewellers of Prince Rainier and Princess Grace of Monaco, and were adored by movie stars such as Marlene Dietrich, Joan Fontaine and Sophia Loren.

They also sourced a number of historically significant jewels around this time, including the early 19th century diadem of Empress Marie-Louise of Austria in 1953 (whose emeralds they replaced with turquoises and sold to Marjorie Merriweather Post), as well as a suite of superb emeralds formerly in the collection of Grand Duchess Vladimir, which VCA purchased from Merriweather Post’s niece by marriage Barbara Hutton (for whom they later made another extraordinary diamond tiara in 1967), as well as the diadem of Napoléon Bonaparte’s first wife, Empress Joséphine.

VCA’s star continued to rise in the following decades, and their aesthetic vocabulary easily embraced the 1950s move towards exaggerated femininity and naturalism, creating spectacular jewels, both in diamonds and brightly coloured precious stones with yellow gold. In 1954 Jacques and Pierre Arpels, Estelle Arpels’ nephews who had joined the firm in 1935, launched the ‘Boutique’ department, which launched limited annual collections of high quality but less formal and less expensive jewels, to be collected and enjoyed by a wider clientele. While the initial focus was on animal and zodiac-themed jewels, particularly the beloved Chat Malicieux (1954), the ‘Boutique’ range also incorporated interesting and versatile jewels which were perfect daytime accessories, including the Twist bracelets, rings and necklaces set with beads of coral, lapis, aventurine quartz and turquoise coiled with strands of pearls, coral-inlaid Philippines rings (1968), and chains of interlocking gold and hardwood links. This range would also see the development of many of VCA’s floral jewels, in particular the enduringly popular Rose de Noel ear clips and brooches (1971), designed as hellebore flowers with petals of carved coral. Most notable was a design of quatrefoil motifs linked along a chain, worn as a long necklace, bracelet or adapted into earrings, known as Alhambra (1973). Alhambra would become one of VCA’s most commercially successful designs and is still one the house’s staples. In their haute joaillerie collections, alongside their opulent parures of diamonds and precious stones, VCA’s jewellery also accessorised the exotic, decadent fashion trends of the 1970s with textured gold sautoirs set with various eye-catching combinations of coral, chrysoprase, turquoise, amethyst and onyx.

Van Cleef & Arpels, alongside their contemporaries Cartier and Boucheron on the Place Vendôme, are still one of the most important and successful jewellers in the world today. Now under the ownership of luxury conglomerate Richemont SA, VCA have expanded worldwide, with collections playing upon their rich history of design, including updated versions of Alhambra, Rose de Noel and their Danseuse brooches, alongside ambitious haute joaillerie collections, and delicate, floral jewels such as Frivole.

Their Heritage department is also particularly active, exhibiting jewels from the VCA archive, and the Ecole Van Cleef & Arpels in Paris is one of the leading education providers in modern jewellery design, continuing their legacy of imaginative jewellery design and painstaking craftsmanship into the 21st century.

You May Also Like