BACK TO LIST

BACK TO LIST

A Well-Trodden Path from The East Paved in Silver

Before entering this wonderful world of what we refer to as Chinese Export Silver I think it is important to touch upon the scholars that have enlightened us and influenced me with regards Chinese Export silver. Dr Crosby Forbes, John Devereux Kernan and Ruth S. Wilkins first brought the world’s attention to Chinese Export Silver with the first exhibition in America in 1966 at the China Trade Museum. Kernan subsequently compiled and wrote the limited-edition catalogue for The Chait Collection of Chinese Export Silver in 1985.

More recently, the exhibition of The Silver Age: Origins and Trade of Chinese Export Silver ran from 2017 to 2019, organised by the Hong Kong Maritime Museum, and co-organised with the Home Affairs Bureau, Hong Kong Special Administrative Region and Guangdong Museum. The exhibition was curated by Dr Libby Chan.

I am also sure most of you will also know Adrien Von Firscht and his enlightening research into a subject which is often misunderstood, particularly with his help in bringing to light hundreds of export retailers and artisans particularly in the Treaty Cities so often ignored in the past.

I would also like to thank the wonderful friends and collectors who I have been fortunate enough to meet that have helped to enlighten me on my own personal journey with Export Silver.

We have come to use the term ‘Export Silver’ very loosely as much produced in China would also have been commissioned for the home market and yet at a later date made its way abroad through trade and gifts. Technically, the term "Export Silver" refers to silver ware produced specifically for export by Asian silversmiths, catering to foreign tastes and demand. This is not something that occurred overnight.

Chinese Dynasties

Han period (-206 to +220)

Tang Dynasty (618-906)

Sung Dynasty (960-1279)

Yuan Dynasty (1279-1368)

Ming Dynasty (1368-1644)

Qing Dynasty (1644-1912)

We must consider that silver has been greatly admired in China for at least 2,500 years. During the Han period (-206 to +220), we see the flow of precious metals with the silk trade. The prosperous Tang Dynasty (618-906) saw great expansion, with the opening of China’s frontiers, which led to ordinary, utilitarian vessels being transformed into silver objects of wonder. The Sung Dynasty (960-1279) saw the emergence of silver items very similar to those made from ceramics and other materials, and the splendour of the Great Khan's Palace in the Yuan Dynasty (1279-1368) was hailed by explorers and travellers, including men such as Marco Polo, for its richness and beauty.

The Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) saw a cultural renaissance and with it a return to forms of antiquity, but it is during the Qing Dynasty (1644-1912) that we see Chinese Export Silver emerge and explode for the foreign market. A wonderful fusion of overseas requirements and fashion mixed with centuries of Chinese tradition created an unmistakable design.

Silver as a form of payment has historically been linked to trades in China. As maritime trade routes expanded, silver coins circulated throughout Europe to the Mediterranean Sea regions that established silver's significant role for trading. The advent of the European Age of Voyages meant the beginning of global maritime trade. Silver coins minted in Spain and Mexico widely spread all over the world and established a system of internationally accepted currency. In China, silver bullions excavated from the shipwrecks of the Tang (618-907) and Song (960-1279) dynasties have proven that silver played an important role as currency in common use in China and Southeast Asia, and have demonstrated the prosperity of ancient maritime trade. Beginning in 1565, Spanish trading ships known as Manila galleons voyaged across the Pacific Ocean from Acapulco, Mexico, to Manila, Philippines, every year for trading. As an advanced voyage vessel, the Manila galleon was made of wood and built by Chinese shipwrights hired by the Spanish in Manila, it had a typical payload of two thousand tons. From the mid-16th century onwards, the Americas and Japan were the major producers and exporters of silver. The total American silver production rapidly increased during the 16th and 18th century and shipped to Asia through Europe and Manila. Japan also exported bulk silver to China during the 16th and 17th century, making China the major silver recipient of the period. Besides functioning as currency, silver had been a material commonly used for making artefacts, along with gold, throughout China’s history because of such characteristics as white and bright colour, corrosion resistance, fire resistance, malleability and ease of splitting and working.

So, China was rich in silver and had based its monetary system on this precious metal, most of which was mined internally in Yunnan and Sunshing. The country had protected its great asset by limiting the export of silver and only permitting it in the form of coin, bullion, or manufactured wares. Its reserves, as touched on before, were further bolstered by foreign trade with the west, and with America and Britain in particular, this trade was conducted in silver trade dollars.

As we all know, there was a fashionable trend of chinoiserie in Europe during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. These chinoiserie imports were highly appreciated and pursued by the royalty and nobility. At the time, handicrafts made in Europe demonstrated certain "Oriental" elements such as Chinese flowers, figures and architecture seen particularly in the artistic styles of Baroque and Rococo. However, early Chinese Export Silver was incredibly rare, and it was only special commissions by Royal households, Ambassadors and nobility that one sees in the late 17th and early 18th century including Europe, India and Arabia as well as to a select number of wealthy American merchant families, mostly on the eastern seaboard. The appeal of the exclusivity and exoticism must have been intoxicating.

© Image courtesey of the State Hermitage Museum St Petersberg by Vladimir Terebenin

This is exemplified by a wonderful toilet service commissioned by Catherine the Great in the Hermitage, St Petersburg and by a beautiful Rice wine pot and tankard circa 1685 both now in private collections.

A 17th Century rice wine pot circa, 1685

A Chinese 17th century tankard circa 1685

However, not long after this, one sees that a significant trade existed prior to the Canton system (1757–1842) and lucrative partnerships were formed with the Chinese Hong Merchants. The Hong merchants were guilds that had the extreme privilege of trading with foreigners from mainland bases. This period initially sees the fashion for Chinese export silver largely following the styles that were found in the west.

Here we see a Chinese Casket Canton, circa 1750 it is interesting to compare the shape to boxes from European toilet services towards the end of the 17th century and early 18th century. The fine filigree work is beautifully executed.

This delightful high-quality tea urn made in Canton circa 1825 by the retail company Lin Chong, is interesting to compare how this creation was influenced from the English late neo-classical period.

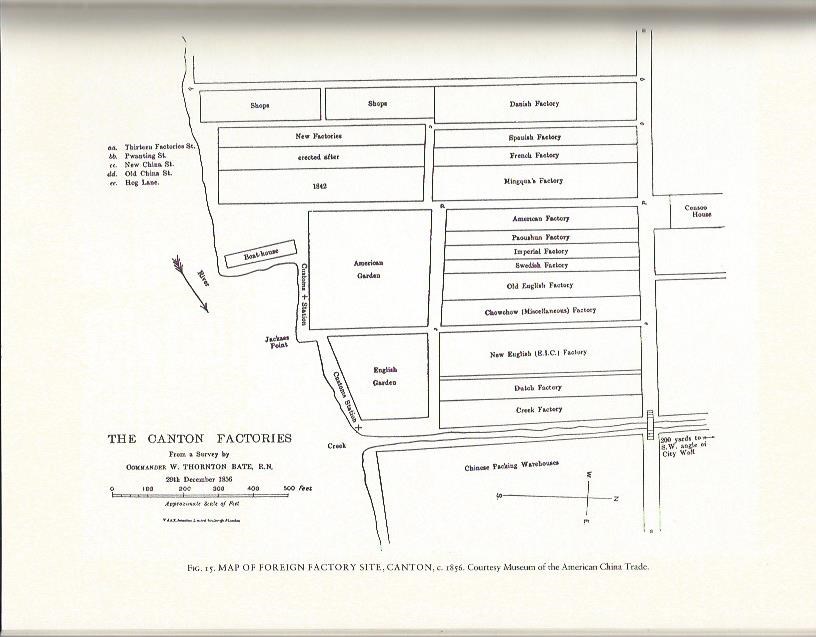

The Canton system served as a means for China to control trade with the west within its own country by forming all trade on the Southern port of Canton (now Guangzhou) The policy arose in 1757 as response to a perceived political and commercial threat from abroad on the part of successive Chinese Emperors. Many fortunes were made at this time through the China Trade and of course the Opium Trade. This system permitted local Hong merchants to govern and secure commercial trade with foreign merchants. They governed the trade of the main commodities such as tea, silk, sugar, and spice. However, it was the 'outside shopmen or merchants' in Canton that provided items for personal use and these, of course, included items made from silver.

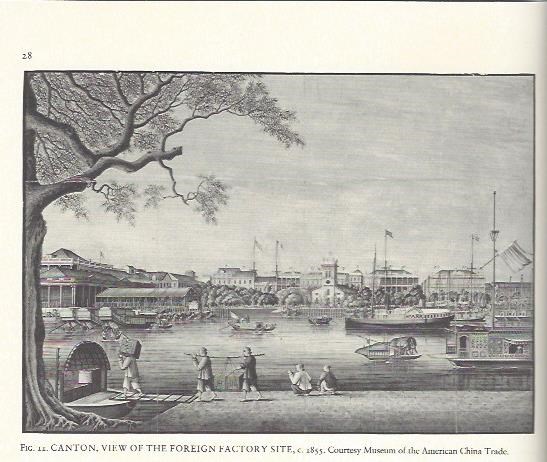

Foreign companies and sea captains were attracted by the relatively low price of said silver items. The highly skilled labour of the Cantonese silversmith was so much cheaper than in the west that even with the additional duties and cost of transport, these purchases were still a very appealing proposition. One can see from this old map of the canton factories or trading posts how international this must have been with the Swedish, Danish, French, Spanish, Dutch American and British all present.

The Hong merchants maintained an incredible and sumptuous style of living with silver very much in evidence. They presented their ‘foreign friends’ with many gifts from the many silversmiths that surrounded the compound, catering of course to the Western tastes. The almost royal status of these Hong merchants was certainly impressionable and this influence of Oriental luxury on the merchant and sea captains passed on when they returned home in the many trappings they filled their houses with to display their new found wealth.

The British set the tone for this luxury in the days of the East India Company foreigners were generally regarded as untrustworthy. The East India Company was unique in that they had the trust of the Hongs. It was the biggest of the factories and noted for the lavish and grand scale hospitality. This continued on the opening of the other treaty ports in 1843 and Anglo-Chinese residences were erected such as Government House in Hong Kong.

The activities of the early Western settlers were also greatly controlled, and they were limited to there compounds. Indeed, the wives of the merchants and Captains on the opening of Hong Kong as a treaty port were only allowed initially to remain in Macao, the Portuguese colony. The early clipper sail boats also only had seasonal access to the ports followed by long and precarious journeys to their final destination. This meant a year-round trip for the merchant with lengthy periods of waiting patiently for the right conditions to sail.

What was one to do in these often-boring times. The time-honoured tradition of shopping whilst in a foreign destination? They filled much of their time with this activity and the silversmiths retail establishments cleverly situated their locations around the compounds. Many competitions also were organised to pass the time including sailing, rowing, and later horse racing. These all would have had cause for their individual silver prizes.

One such prize is this incredible 19th Century Bowl on Stand

Silver and Original Carved Wood Stand made in Shanghai, circa 1890

The silversmith and chop mark of DA JI who was working for the great firm of Hung Chong & Co in Shanghai.

Diameter: 39 cm, 15.35 in

Weight: 4960 gr, 159.49 oz

Inscription referring to the Amoy Races, the modern city of Xiamen

Hung Chong & Co was a retail silversmith with its own manufactory or workshop and was owned by Fok Ying Chew. The retail store opened in 1892 after the manufactory began.

The following article appeared in a 1908 published travel journal of an Englishman and repeated verbatim: “The Chinese are admittedly clever craftsmen and the silver-ware which they manufacture is very popular with collectors of Eastern curios and souvenirs by reason of its quaint beauty. Among the leading gold and silversmiths in Shanghai are Messrs. Hung Chong & Co., who deal largely also in blackwood furniture, embroideries, silk piece goods etc. Their premises at 11b Nanking Road always present a very attractive appearance. The business was established in 1892 by Mr Fok Ying Chew, who sold it in 1906 to the present proprietor, Mr Sum Luen-sing. The large trade carried ion necessitates the employment of fourteen assistants and forty-workmen. Mr Sum Luen-sing is the son of Mr Sum Cheuk Sing and was born in Macao in 1871. He studied English in Shanghai and at the age of sixteen joined the “Limpu” Line of steamers. After remaining in this employment for three years, he obtained a post with the “Kang-yue” Line. He joined Hung Chong & Co. as an assistant in 1892. He is married and has one son and daughter.”

The end of the Opium Wars and the signing of The Treaty of Nanking in 1842 opened many other Treaty Ports for trade. Foreign settlements established themselves in Shanghai and as mentioned already Hong Kong, as well as in many other centres, such as Juijang, Nanking, and Tientsin. Initially, silversmith shops were branches of established Canton firms but with the immense trade that exploded in the following years and the huge rise in affluence, numerous new businesses and silversmiths gained a strong foothold in the market.

I find this pair of exceptional beautifully decorated cachepots particularly interesting as they are made in Peking circa, 1880 by the maker Bao Heng Xiang

Here is a very special commission, a gold freedom box made by Johh Linnitt in 1844 celebrating the signing of the Treaty of Nanking, the plaque on the cover chased with the British and the Chinese gathered round a table, framed by a border of heraldic flowers, all on a matted ground, with a dove bearing an olive branch above, with trophies and arms at the angles, the sides and base engraved with shells, scrolls, flowers and pagodas, incorporating the arms of Pottinger, with Cooke in pretence, and the City of London, the interior of the lid with a presentation inscription which reads:

A common council holden in The Chamber of the Guild Hall of the City of London. On Thursday the 13th Day of February 1845.

Requested Unanimously

That the freedom of this city in a box of the value of one hundred Guineas be presented to Major General Sir Henry Pottinger Baronet G.C.B.

In testimony of the estimation entertained by this court in common with their fellow citizens in regard to his important services in negotiating a treaty of Peace and Commerce with the Chinese Empire

MEREWETHER

The plaque on the cover is after a painting by Captain John Platt.

The rapid expansion of the aforementioned commercial centres, such as Hong Kong and Shanghai saw the production of every ware imaginable in silver. The cost of silver was high for the firms selling their plate, so although some stock was immediately available to the purchaser, most items were generally special commissions.

General items would have included pieces such as the snuff box. The history of Chinese snuff boxes is closely intertwined with the introduction of tobacco products in China during the mid to late 16th century. Tobacco was smoked initially, but when the Portuguese traders arrived and presented snuff as a gift to the Chinese Emperor at the court of Beijing inside a wonderfully elaborate European-style snuff box, it quickly superseded smoked tobacco. Snuff was very expensive and became part of the social ritual at the Qing Dynasty's imperial court as noblemen came to sample this new wonder which was believed to have medicinal properties. By the 18th century, the practice had spread to every social class in China. Not only were these precious boxes fashion accessories, but they were also a means to express social status.

Interestingly, the humid climate in China, together with the introduction of established medicinal practices, changed the shape of vessels for snuff used in China. The European boxes were lightly sealed and caused the snuff to cake. They were soon replaced by snuff bottles which had air-tight stoppers. The Chinese Export Trade however for the traditional European-style snuff box continued to flourish. Individual commissions were often personalised, for example for a marriage, carrying Chinese characters wishing the couple a long and prosperous life, or alternatively with symbolism such as a phoenix and dragon for wedded bliss and matrimony.

Many items purchased in the Chinese Export Trade related to tobacco and these included cheroot cases, cigar boxes, cigarette boxes, vesta boxes and match box covers.

A CHINESE PRESENTATION CIGAR BOX

Maker’s Mark of Wang Hing

Circa 1890

Weight with liner removed: 100 oz

The front panel is embossed and chased with a village scene, the back with an agricultural scene, bamboo forests to the sides, the hinged cover with presentation inscription bordered by chrysanthemums bordered by peonies, hinged simulated bamboo handles, raised on four ball feet, opening to reveal a cedar wood liner.

Inscribed: ‘Presented, to, The Hon ble Charles S. Pearse, Treasurer of Sarawalk, 1875-1898, by his brother officers, as a token of friendship and respect on his, retirement from the , Sarawalk Civil Service, July 31st 1898’

Together with the original list of the subscribers.

Rajah Charles Brooke was so grateful to Charles S. Pearse that he named a road in Kuching after him. Pearse was instrumental in installing a proper accounting system for the White Rajah’s Sarawalk government’s accounts, which had been in a mess until then. Pearse was then appointed Treasurer of Sarawalk and a member of the Supreme Council and the Council Negri.

Other general items would have included boxes of every manner from bougie boxes through to seal boxes, dinner service would also been very popular items, flatware, card cases, vinaigrettes, and caskets to name a few.

The Punch bowl would have been one of the centrepieces of this high living and entertainment of this opulent period and undoubtably would have been a special commission and not a piece one could purchase from the shelf. The ability of the Chinese silversmith to turn around such sumptuous commissions in a relatively short space of time was truly astounding. Here I show a number examples which demonstrate the variety of decoration and styles at the same moment in time.

This is a massive 19th Century Chinese Punch Bowl made in Shanghai in 1888 and retailed by the firm Hung Chong & Co

Weighing some 93oz 2dwt of silver

This exceptional punch bowl on three dragon feet, cast and applied to the raised bowl. The main bowl with cast and applied dragons together with the sun emblem to the centre. The firm of Hung Chong were based in Club Street in Canton as well as Nankin Road Shanghai between 1860-1930

Here we see a superb Chinese Punch Bowl made by the celebrated firm Wang Hing. They had outlets in Hong Kong, Canton & Shanghai. This bowl was made circa 1895.

This punch bowl show how international Chinese Export silver became, It bears the additional import hallmarks of Edwards & Sons in Glasgow for 1895.

This magnificent punch bowl was made in Shanghai circa 1890 and retailed by the firm of Luen Wo. The exterior is embossed in high relief with scenes of dignitaries hunting and an additional scene of a court, there are further figures in a mountainous landscape and the sides with loose drop ring handles suspended from lion masks.

The interior of the bowl is inscribed ‘Die dankbaren Deutschen Shanghai I.L. Dr Paulun 1895’. Again, demonstrating the European appeal, this time for the German traveller

Here is a beautiful punch bowl by the celebrated retail establishment of Wang Hing circa 1890. The fabulous use of cloud dragons leaves no part of the surface undecorated save for the pierced elements.

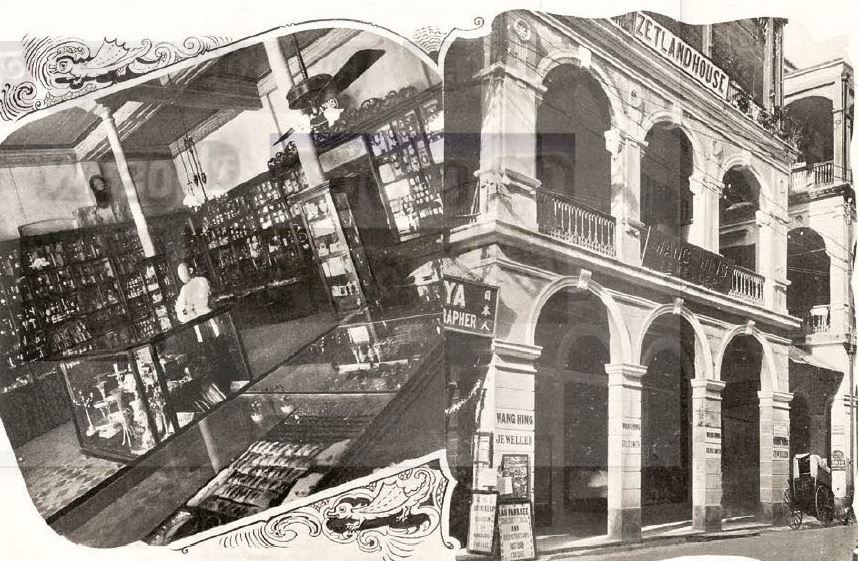

The celebrated firm Wang Hing & Co was based at Zetland House, 10 Queen’s Road, Hong Kong 1 Sai Hing Street, Canton & also in Shanghai.

Wang Hing was probably responsible for producing more Chinese Export Silver than any other Chinese retail silversmith. The company was also one of the first to establish a large retail emporium that grew to sell a wide variety of luxury goods. Wang Hing & Co begun just after the 1842 Treaty of Nanking by the Lo Family, who lived in Xiguan within Shameen Island in Canton where the 13 Hongs had been situated. In the late 1860’s, the eldest son Lo Kit Ping took the helm. It wasn’t until the early 1920’s that a purpose-built flagship store was decided to be built on the Queen’s Road, Hong Kong. This store was run by Lo Hung Tong. The Lo family members insisted on designing and overseeing the quality of every item of silver that was made for them and it was from their Hong Kong emporium they fast established the reputation as the place to go to order bespoke trophies and commemorative items that became part of the thriving men’s clubs and sporting clubs that became synonymous with Hong Kong. Sadly, the success of this great firm ended in 1941 with the invasion of the Japanese.

They would have undoubtedly influenced styles in the West that became so popular with department stores such as Tiffany with high style of Chinese symbolism and Western fusion.

Here you see their flag ship store at Zetland House in Hong Kong

This fabulous punch bowl again by the firm Wang Hing was presented as the winning prize at the Kong Kong Jockey Club, highlighting their production for one of the many sporting clubs.

The history of tea and its relationship with foreign trade and China is another academic paper in its own right, but the variety of boxes or canisters that were made to carry black (Bohea) and green (Viridis) tea is extraordinary. The west fell in love with this magical leaf and built its social and political infrastructure around the tea ceremony during the 18th and early 19th centuries. Chinese Export Silver capitalised on this. The word 'caddy' derives from the Malay kati, meaning approximately 1⅕ pounds. The cost of tea during the late 17th century in England was high: 40 shillings per pound in 1664. However, it was never higher than when it became heavily taxed in the 18th century. The earliest examples of silver tea caddies emulated the Chinese porcelain examples and were often inserted with lead liners to preserve the tea. The variety of shapes, style and decoration is amazing.

A Chinese tea caddy circa, 1900 decorated with Chrysanthemums

A 19th Century Chinese Kettle

Circa, 1905. Marked under base with the silversmiths’ chopmark The kettle-on-stand with similar chrysanthemum flower decoration.

The provenance to this piece a Mr James Linn Rogers (b. 1861), Consul-General of the United States at Shanghai from 1905-1907, and thence by descent, highlights the International appeal of Export Silver

CHINESE SILVER THREE PIECE TEA SET, by Wang Hing, of hexagonal section, repoussé decorated with panels of figures, dragons and flowering foliage and with simulated bamboo handles, This set, although not photographed here, came with its original fitted silk-lined hardwood box with sliding cover. These original cases with the retailer labels give us great insight to the location and operations of these original firms of the treaty ports.

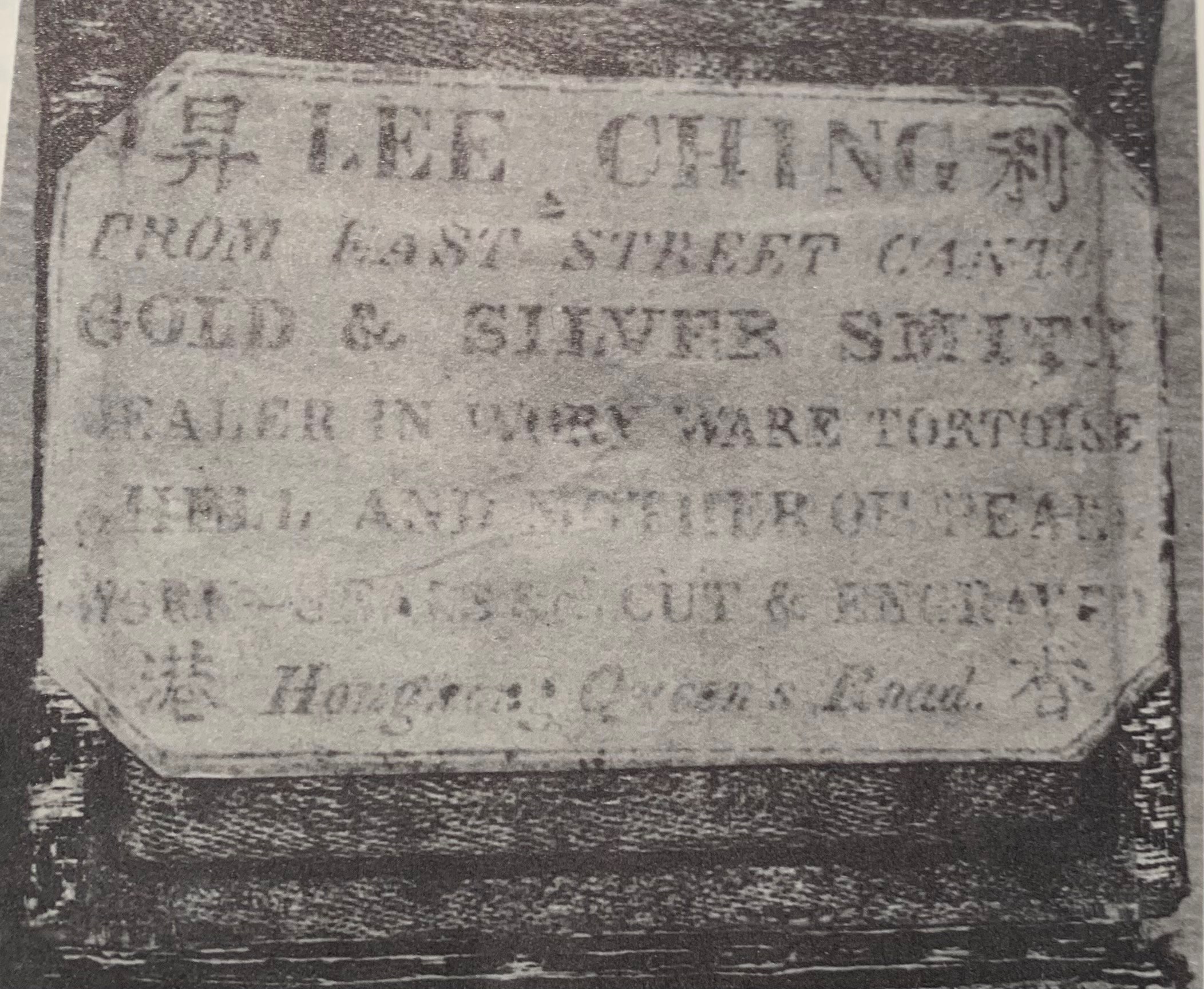

One such label of the Firm Leeching Canton, circa, 1850-60

Courtesy Museum of the American China Trade.

The rapid expansion of the treaty ports continued as clipper sail boats were peplaced by steam boats, this meant the start of tourism and indeed with it department stores. The once elusive and and unobtainble items became more readily available still in the early Republic (1912-1949). This of course would have ceased with the outbreak of Worl War II

A 19th century Chinese school picture of the Bund in Shanghai

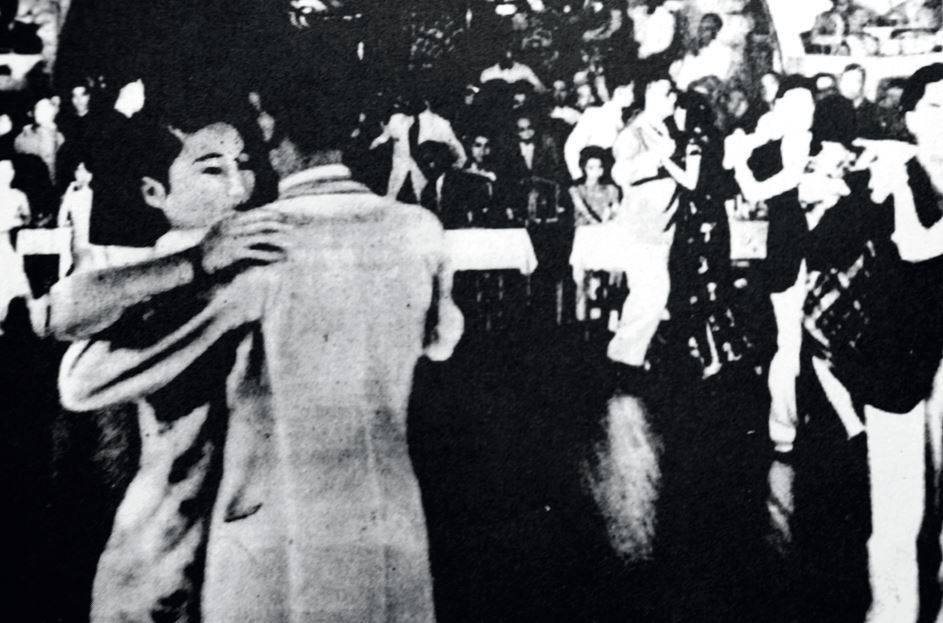

The Jazz Period in Shanghai is well documented. The city of Shanghai was divided into zones controlled by different governments, warlords, and foreign powers including the Japanese, British, and French. In this political no-man’s land, Shanghai became a crossroads where people from all continents met on the banks of the Huangpu River.

Americans, Russians, Chinese, Brits, Japanese, and a host of other nations’ peoples contributed to the boisterous world of Shanghai’s night-time entertainment. The city was full of jazz bands and combos who could all play the latest popular numbers from America and Europe, although many of the musicians were from the Philippines. The silversmiths were quick to cater for this moment in time.

A CHINESE COCKTAIL SHAKER

circa 1900 Retailer’s mark of the Chinese Jewellery Company

AN UNUSUAL 20th CENTURY CHINESE SILVER FOUR-PIECE TEA & COFFEE SERVICE WITH TRAY

China 20th century

Tientsin

Retailer’s mark of Yu Chang

Weight (gross): 182 oz

Of octagonal form with wood scroll handles, the pots and sugar dish with bayonet-fastening lids applied with stepped-circular wood finials each inset with silver disc, the two-handled tray of rectangular form

Provenance:

Presented as a wedding present by La Banque Indochine of Tien Tsin in 1947.

Silver Quality

The quality of the silver produced is also interesting to touch upon. When tested today we see that the finesse is high in quality but varies between 80 -98 percent silver. To quote from an old account in Forbes’ book on Chinese Export ‘Much as we hear of the 100 touch sycee there is in reality no such thing, the very finest made averaging at most 98.5…. In practice, it will be found not an unsafe plan to average the touch of all sycee whatever at 98’ The sycee was the form of ingots used by the Chinese and referred to as shoes by the Westerners because of their peculiar shape.

The practice of hallmarking Chinese Export in the initial case was often a series of pseudo-London hallmarks which would in English Wares indicate 92.5 percent pure in quality. However, this does not apply the same guarantee with Chinese Export silver. The later system of a artisans chopmark, retailers’ hallmark and quality mark of 90 cannot be taken literally. That said, the fineness of silver is incredibly high and more often heavier in gauge when compared to that of a Western object of similar use.

Here we see one of those pseudo hallmarks. This is an interesting example as it closely resembles that of Eley, Fearn & Chawner on a hallmarked piece of London, 1808. This silversmith operated in Canton between 1820-1880.

Here we see a variety of marks used by the famous retailers Wang Hing showing the use of the ‘90’ hallmark together with that of the WH for Wang Hing and the artisans chopmark.

Chinese Export silver is a fascinating subject that I feel I have had the privilege of just touching the surface of. The fact that no Westerners took over as silversmiths in these ports is in stark contrast to that of say India where the firms such as Hamilton & Co were originally from the UK. It is a testament to the Chinese artisans’ incredible skills and the retailer business acumen and ability to adapt to their surroundings that leaves us with so many treasures to admire today. Here are a selection of these masterpieces as a testament to this fabulous fusion and unique style we call Chinese Export.

An Extremely Rare Chinese Parcel Gilt Garniture

Silver Gilt

Shanghai, circa 1870

Maker's mark of Quan Ji

Retailed by Leeching (Lee Ching) of 24a Queen’s Road, Hong Kong 30 Old China Street, Canton Nanking Road, Shanghai. The firm of retailers was active between 1840 and 1880 circa.

The incredible quality of this garniture, comprising of two parcel gilt candelabra and a casket, makes it an exceptional piece of Chinese silver. The design of the pieces is highly unusual as such architectural pieces differ from the most common examples of objects produced in the Shanghai region at the time.

The two candelabra sit on large square feet that recall the shape of traditional carved wooden bases for precious objects. The stem is adorned with a coiling dragon and a geometrical decoration connects the stems.

The body of the casket is shaped as a pagoda resting on four sharp feet with geometrical patterns and naturalistic clouds inside the reserves. The garniture is of Imperial quality and it is likely the client would have been a Comprador or possibly more westernised prince.

An Exquisite 19th Century Chinese Cup & Cover

Silver

Circa, 1890

Maker's mark of Wang Hing

This cup and cover bears the hallmark of Wang Hing in a square lozenge that is found on other pieces from the Wang Hing firm. This mark is that of the silversmith Tai Kut, who was a known silver workshop as well as a maker for Wang Hing & Company.

The cup and cover has fantastic detail with scenes of temples to one side and warriors to the other. The base also has superb sea motifs of fish, sea snails and crustacean.

A Chinese Centrepiece, Shanghai circa 1890 by Luen Wo

The body is ornamented with twelve shaped panels with matte backgrounds. Each panel is embellished with chased decoration depicting individual scenes, such as birds sitting in a cherry blossom tree, fish in a pond, figures in oriental attire conversing on a balcony and chrysanthemums amidst foliage. The shaped rim of this impressive centrepiece is encompassed with an applied moulded border. The body surmounts a magnificent pedestal encircled with three cast three-dimensional oriental bearded dragon ornaments to a chased smoke/cloud decorated plinth. The knop to the lower portion of the large pedestal is embellished with further chased decorated panels matching the designs to that of the body. The large circular domed spreading foot of the centrepiece is encircled with further chrysanthemum and foliate decoration on a matte background.

The decoration to the foot is encompassed with a plain border, incorporating the contemporary engraved inscription 'To J.R.Greaves Esq. From A.Ebrahim & Co. Shanghai'

Diameter of rim 31cm/12.2"

Diameter of foot 20.5cm/8.1"

Height 25.5cm/10"

Weight 63 troy ounces/1960g

A Chinese Export Silver 19th Century Canister

Silver

Canton, circa 1890

Retailers mark of Cum Shing of Old China Street, Canton c.1775-1840

Height: 23.5cm, Weight: 11,11.2g, 35oz 14dwt

The canister of cylindrical form with lobed sides, embossed with alternating panels. The panels decorated with birds in blossom trees, figural groups, rampant dragons and climbing bamboo and chrysanthemum. Each side of the canister with applied grotesque winged masks carrying ring handles. The cover embossed with cloud dragons, terminating with a cast dragon and pearl finial. The main body raised on four stylised bamboo bracket feet. The canister with gilded interior.

A Chinese Gold Cup

Gold

Circa 1910

Height: 14.5cm

Weight:284 gr

Maker Wu Hua

This gold standing cup is unusual simply because in having been created in gold. It carries a 750-gold mark: equivalent to 18 carat. It is decorated using both Chinese and English influences; the use of the English oak leaf motif where the two handles meet the body of the cup could well be in recognition of the British Navy. A cup of similar form exists that was made in Canton circa 1905 for the Peking Club Billiard Handicap. The rim of this gold cup is decorated with a prunus motif border.

Wu Hua, Tianjin is the same Wu Hua as in Beijing. As with some of the more prominent artisan and retail silversmiths in Beijing, Wu Hua decided to relocate to Tianjin when fighting broke out in Beijing. Despite the fact the very same happened in Tianjin, most of the Beijing “refugee” silversmiths stayed in Tianjin. Wu Hua, however, retained the Beijing shop for several years.

Wu Hua operated two premises in Tianjin, one in the Japanese Concession and the other in the French Concession. They stayed in operation until circa, 1937 when the Japanese invaded and captured the city.

A Chinese Dumpling Dish

Shanghai & Singapore

Circa 1890

Maker's mark of Tian Xing

This is one of the most unusual of Chinese Export silversmiths but is known for the extreme quality found in the few surviving pieces found with his mark. This extraordinary piece is highly decorated with phonenixes , flowers and crustacean

A PAIR OF CHINESE EXPORT FIGURAL CENTREPIECES

Silver

Hong Kong, late 19th, circa, 1880

Maker’s mark of Wang Hing

Height: 17 ½ in (44.5 cm)

Diameter: 11 in (28 cm)

Weight: 152 oz

Each with bamboo-form central stem, amidst cranes, supporting similarly decorated tiered dishes, surmounted by a conical vase, over dragon-form standards above a tripartite base decorated with dragons and scrolling foliage, on bat-form feet.

The cranes and bats have added symbolism of longevity and peace

I hope you have enjoyed this very short insight into an incredibly fascinating world. It is hard to do this subject justice in such a short blog, as there are so many areas to expand on. As you can imagine these objects are keenly sought after by the many collectors and museums around the world. Chinese Export silver has a truly international collector and is fuelled by the Chinese and their re-kindled interest in revisiting an incredible period of the Chinese silversmith.

Timo Koopman

© Koopman Rare Art, all images and information with exception of those with courtesy of other named institutions.