BLOG & ONLINE CATALOGUES

A Magnificent Private Collection of French 18th Century Candelabra To be Shown at TEFAF Maastricht 2025

08 February 2025

The title ‘Design’ looks to the genius behind the hallmark of our celebrated goldsmiths. Too often overlooked, this brief paper, glorifies and studies in more detail some of those draughtsmen, artists, sculptors, modellers and architects that conceived these splendid designs which in turn, were executed to perfection by the goldsmith to create the finished masterpiece. The 18th and 19th century designs were often inspired by the ancient world. The author’s drawings stimulated the taste for academically inspired ornament in Greek, Roman, and Egyptian styles and drew inspiration from those that had been on the Grand Tour.

01 February 2025

To celebrate Year of the Snake, I thought it would be the perfect time to introduce my latest Director’s Choice. The world celebrated Chinese New Year yesterday and according to Chinese tradition, the Snake is a symbol of good fortune and prosperity, and honouring the Snake is believed to invite positive energy into one's life. Celebrations included decorating homes with red, a colour linked to luck, and lighting fireworks to drive away any negativity or bad spirits. It’s a time to reflect, celebrate the present, and hope for a prosperous year ahead.

17 January 2025

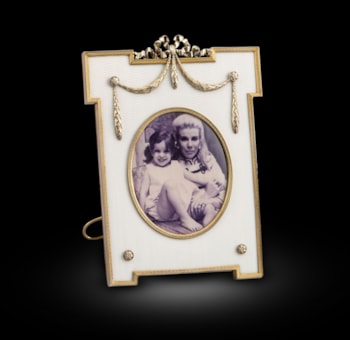

Hong Kong family collection A woman of taste is without doubt a fine description of Mrs Lillian Li. For the 44 years I have been connected with the Koopman family, Mrs Li and her family have been an integral part of our lives. In 1983 she invited us to hold an exhibition at the new Regent hotel, Hong Kong. One never liked to turn down one of her graceful invitations, and we knew that she had our best interests at heart. This was very new for us and extremely exciting. Michael (Timo’s father) Leisje (Jacques’s daughter) and I were thrilled at the prospect of this visit to Hong Kong. With this invitation a whole new world and clientele opened up for us. We arrived in Hong Kong with twenty trunks full of wonderful silver and held a selling exhibition that was memorable and attended by so many. Obviously, whilst we were there, she beautifully hosted fabulous lunches and dinners to which she also invited many of her friends ensuring our success at this new event. The dinners themselves were magnificent, and among the many fond memories of that trip is my lesson in the use of chopsticks (I had never had a Chinese meal before) as I sat beside our fabulous hostess. Mrs Li along with her gentle and charming husband Judge Simon Li came from a golden era when entertaining and living was always done properly, with grace and style. We are very honoured that her family have entrusted us to work on some of the family silver now that it has passed to the next generation. The quality displayed in this small selection has always been a mainstay of Mrs Li’s choices, and she would hopefully enjoy and approve that these gems will be going to beautiful new homes. Whilst this is a small and select part of this collection, we hope that you will enjoy reading about these treasures which graced the Li family home. A selection of these exquisite works will be exhibited at the forthcoming Winter Show in New York. Lewis Smith

26 December 2024

The Ferguson Marine Centrepiece The Neptune centrepiece in the Royal Collection has been discussed at length by Kathryn Jones and Christopher Garibaldi (‘Crespin or Sprimont? A Question Revisited”, Silver Studies, the Journal of the Silver Society, No. 21, 2006, pp. 24-38). Described as ‘the purest rococo creation in English silver’, it formed part of the table service displaying the most advanced French taste of the period. The marine theme of the piece, with its Neptune finial, swags of shells and pieces of coral and detachable dishes in the form of abalone shells, suggests it was used to serve fish soups and seafood. Bearing the touch mark of Paul Crespin on the plateau it is accompanied by sauceboats of 1743 and four salts which are by Nicholas Sprimont. It was further embellished by Rundell, Bridge and Rundell in 1826 by raising it on glorious hippocampi. The centrepiece modelled as a large shell supported by a frothing pillar of water, the triform base guarded at each of its three points by hippocamps on a crashing wave base, the feet composed of turtles, coral and shells, the bowl engraved with two coats-of-arms.

21 December 2024

Director’s Choice – The Duke of Hamilton’s Candlesticks By Paul Storr These superb candlesticks commissioned by Alexander Hamilton, the 10th Duke of Hamilton glorify the prolific collecting of an extraordinary man driven by an intense desire to demonstrate his wealth, status and power. They capture the new rococo-revival style of the early 19th century perfectly and are exceptional in form, execution of finish, condition and gauge weighing an incredible 6,860g, 220 oz 11 dwt. Bearing the touch mark of the goldsmith Paul Storr when at his very best, they are my Director’s Choice this week. These magnificent cast rocaille candlesticks rest on shaped circular bases with cast and applied floral decoration with roses, rose-hips, grape and vine decoration together with sweeping rocaille swirls. The stems with acanthus capped top and bases the capitals in similar matching décor to the bases. The fluted sconces with scrolls and foliate rims

14 December 2024

The Koopman Rare Art Illustrated Directory of Gold & Silver C is for Cumberland The collection of treasures we currently have here at Koopman Rare Art that at one time graced the tables and sideboards of The Palace of Herrenhausen in Hanover inspired me to focus on the plate owned by this remarkable character Ernest Augustus Duke of Cumberland and later King of Hanover. To this day, both major institutional and private collections consider items with this provenance amongst the most important within their collections; not only for the fine quality and provenance of the items but the remarkable story they tell. We are very proud to present five triumphs of the decorative arts that were part of his collection and help paint a better picture and understanding of the majesty of this period and the incredible heights achieved by the royal goldsmiths competing to lure that next glorious commission.

07 December 2024

Director’s Choice – Timo Koopman A Monumental George III Warwick Vase The detail and size of this Warwick Vase is exceptional. It is one of the earliest and largest examples known in silver. This commission pushes the boundaries of what is achievable and is an incredible triumph of the goldsmith. Measuring fifty-six centimetres or twenty-two inches in height, it weighs an astonishing 13,220 grammes or 425 troy ounces and 1 penny weight of silver. The vase has two large handles formed as interwoven vine branches, from which the tendrils, leaves, and clustering grapes spread around the upper margin and features classical Bacchic masks and associated emblems, such as the pine tip staff or thyrsus. The middle of the body encompasses the pelt of a panther, with head and claws, the cloak worn by Bacchus. Above are heads, all representing satyrs, except one, which is that of a female, traditionally said to have been substituted for a missing head and made by an Italian carver in the 18th century into the likeness of lady Hamilton; however, as the result of a supposed quarrel with her, the carver gave lady Hamilton’s head a fawn's ear. This monumental triumph rests on a square pedestal foot.

30 November 2024

Directors Choice – Timo Koopman The Mokumé Tiffany Bowl This week Director’s Choice focuses on an incredibly rare piece of Tiffany silver commissioned whilst the firm was under the direction of Edward Moore. This fascinating bowl uses a technique called Mokumé, which means “wood grain,” and is the term used for a Japanese metalwork technique which combines and manipulates a metal laminate of different coloured metals (gold, silver, copper, and other alloys) to create the appearance of wood grain. The pattern results from punching through the metal layers and then compressing them into a single plane.

27 November 2024

Kimberley’s top jewellery picks for Christmas (there’s only 1 months to go!) The lights are up, the weather is cold, the pubs are packed – it can only mean one thing… Christmas is coming! And with that in mind, the ever important question of what to buy your loved one as a gift. To make this decision easier for you, I have put together a list of my top 10 Christmas picks for jewellery gifts under £15,000. All wonderful jewels that can be worn day or night and on regular occasion; each one would make a very special gift

23 November 2024

The master chaser Johann Otto Christian Saler (Augsburg 1733 - Berlin 1810) was a portraitist, engraver and wax-modeller. Saler, or Sahler, made wax portraits of the Prussian and Russian royal families. He taught drawing at The Akademie in Berlin from 1770. "Hr. Otto Sahler, Wachsbossierer, u. Pastellmaler, lehret die Anfangsgünde im Zeichnen, w. in der Siropstr." according to the Prussian Adre-Kalender...Berlin und Potsdam for 1798. He is identified as the Johann Otto Sahler who made the copy "auf Röthelart" (red chalk) after a head of Van Dyck in Dresden in 1765. However, this beautiful gold box clearly demonstrates Sahler’s background as modeller, in the exquisite cast scenes portrayed in the panels and as a master chaser in the number different tools used to achieve the vast array of textures and depth of the bas-relief. The perfection of the stippling, the softness of the sweeping trees and the subtleties of the details in the faces of the huntsmen and beasts of quarry are outstanding and this is one of the few boxes to have survived bearing this genius’s signature. It is an easy selection as this week’s Director’s Choice.

16 November 2024

Since we started building our collection of jewellery three years ago, we have mostly prioritised purchasing rare and unique antique pieces, mostly made between 1850-1930. Though over the past year we have noticed a shift in taste, including our own, and have accumulated a wonderful selection of 1950s-1980s jewellery. Our main focus when purchasing any jewel is its wearability, and I have found this more modern jewellery (if we can call 1950s modern!) to be extremely wearable and very on trend in today’s market, for any age. It is the kind of jewellery you can dress up or dress down due to its versatility and timelessness, and has definitely become part of the growing trend of wearing “vintage” jewellery.

09 November 2024

These spectacular French Wine Coolers formed part of the magnificent and important dinner service commissioned by the Grand Duke Mikhail Pavlovich. They capture Fontaine and Percier’s designs in their perfect harmony of neo-classical elements alongside Egyptian architecture, presenting the perfect frame for the Duke’s coronet and joined cyphers. French Empire at it’s very best and we are proud to present this week’s Director’s choice.

26 October 2024

Strasbourg is a city steeped in history of the goldsmith and its geographical location on the Rhine River has had clear influence from both the German and French courts to create an individual and spectacular style recognisable for its crisp lines and superb craftsmanship. The goldsmiths of Strasbourg have always had a penchant for the richness of gilded silver, and it is with this in mind that I introduce this weeks Director’s Choice. It is rare to find individual pieces in such good condition from Strasbourg but to find fourteen pieces belonging to one toilet service survive together with such a fascinating history is truly exceptional.

19 October 2024

With the success of our exhibition at Frieze Masters and our focus on the The Magnificence of the Empire and Regency Periods, for the second instalment of The Koopman Rare Art Illustrated Directory of Gold & Silver, we thought it would be natural to focus on the Royal, imperial goldsmith Martin-Guillaume Biennais.

08 October 2024

Koopman Rare Art is thrilled to exhibit at Stand C13 at Frieze Masters in London's Regent's Park from 9 to 13 October 2024. For our exhibition, we present a fascinating comparison of the treasures commissioned by the most important families and royal households at the beginning of the 19th century. We look in depth at this fascinating moment in history on both sides of the Channel and the significance the heads of state played in this incredible period of the decorative arts.

05 October 2024

The Empire and the Regency Style were born out of the formal Neoclassicism that dominated late eighteenth-century European buildings and decoration. These styles were stimulated in large part by the bitter rivalry of France and England and their rulers. Napoleon I (1769-1821), self-styled Emperor of the French, chose to extend France’s imperial grandeur through force of arms. Upon assuming the throne in 1804, he immediately launched an ambitious art and design program that lasted until his reign ended in 1815. Across the English Channel, the Prince Regent, the future King George IV (1762-1830), sought ways to celebrate England’s heritage through his active patronage of the arts. This magnificent pair of Paul Storr candelabra are my Director’s choice this week.

28 September 2024

In the second decade of the 19th century the taste for naturalistic ornament gathered speed. Nostalgia for the previous asymmetrical continuous movement and vision of Meissonnier and the rococo period, once more rose to the height of fashion. Casting was such an important element and works were inspired from originals by Crespin and Lamerie of the 1730’s and 1740’s and given a new lease of life with superb chasing. These salt cellars made in 1835 by Paul Storr for the famous Pembroke service capture this moment in time perfectly. The cast elements such as the beautifully modelled putti have such amazing detail in their faces, feet and hands and the fluidity of design capturing the rococo feel is perfect. The chasing in the diaper-work and rosettes gives these salts lively character offset by the pearls symbolising Venus and the love of dining. They are my Director’s Choice this week.

21 September 2024

There is no doubting the expansion of both the population of London in the Elizabethan period and the leap in the economy largely due to the increase in trade overseas; encouraged by the infrastructure put in place to harness this growth. This new wealth, as well as the reformation of the church under Henry VIII, influenced the activities of the goldsmith in England, creating a huge demand for new plate and in particular silver for the communion. However, the silver tankard together with other drinking vessels had a special place in the 16th century with the diversity at this period was much broader in range than in later centuries to come. David Mitchell’s most recent book on the Wider Goldsmith’s Trade in Elizabethan & Stuart London certainly highlights this fact with an insight into the records at the goldsmiths’ Company Court Books, 1560 -1679, pg. 170. Communion cups, Magdalen cups, Beer bowls, Cans, Tankards, Tavern bowls, Monsieur bowls and Tavern cups are listed to name but a few. The owners social and political status also had a large part to play in the production of the tankards too. Our tankard was most likely part of the household’s buffet. The buffet display of plate was an important feature of medieval and Renaissance banquets. Often made of oak or walnut, buffets usually stood at the side of a dining room, their shelves filled with tablewares. Gold and silver vessels were displayed to convey a sense of the owner's wealth. Normally these vessels were used for the service of food and drink, but on great state occasions they would be set out purely for display. The ritual of dining and the fashion of the food that was served in the Elizabethan period would again have played a part in this treasure’s creation. Taking your tankard from the buffet to your place at the table would have caught the attention of others and made them focus on your silver tankard or in this case, the even more opulent gilded silver used to create this tankard makes it all the more special. The fact that this was originally one of a pair of Elizabethan tankards together with its pristine condition makes this glorious object my Director’s Choice for this week.

14 September 2024

We return after a small break with this week’s Directors Choice. The sumptuous silver-gilt, enamel and crystal cup and cover of Neptune holding aloft his hippocamp. The history of Viennese enamels is renowned, but this example incorporates every aspect of the craft from the beautifully modelled and cast Neptune to the intricately carved rock crystal and sumptuous array of bright enamels, pearls and precious stones. This is a glorious moment in the 19th century, where the skills of the Renaissance were revisited and Hermann Ratzersdorfer brought glory to the city of Vienna.

07 September 2024

With Frieze Masters fast approaching in October and so many of our friends returning after their summer break, I thought this would be the perfect opportunity to introduce our new monthly article that will run alongside our weekly Director's Choice. We will be covering the Alphabet, this will include some of our most special pieces past and present while also exploring the virtuosity, ability, and techniques employed by the finest gold and silversmiths to achieve these treasures that are handed down to the next generation of fortunate custodians. We start the journey with one of our latest acquisitions: An exquisite Swiss gold automaton musical box, amongst the finest gold boxes ever to grace our collection.

23 June 2024

Our superb collection of candelabra date from as early as 1739 through to 1962. This collection will be on view at our forth coming Treasure House Fair here in London 27th June - 2nd July.

22 June 2024

Our Director’s Choice this week focuses on the history of the candelabra. It is released alongside our online catalogue on The Koopman Rare Art Collection of Candelabra which we will be showcasing at The Treasure House Fair here in London 28th June - 2nd July.

15 June 2024

We all recognise the retailer - silversmith relationships which existed between Rundell, Bridge & Rundell and Paul Storr as well as Kensington Lewis and Edward Farrell, there is also good evidence to suggest that William Elliott was chief supplier of new plate to the goldsmith and jeweller, Thomas Hamlet (1770-1853). Trade cards, billheads, advertisements, newspaper reports and existing examples of silver and silver-gilt are abundant evidence that the early 19th century London goldsmith, Thomas Hamlet counted among his customers members of the British royal family. These included, George the Prince of Wales, later George IV, Frederick Augustus the Duke of York and their sisters, the Princesses Augusta, Elizabeth, Mary and Sophia who were all purchasers at his shop in Princes Street, Leicester Square. Whilst Thomas Hamlet was Goldsmith to the King, his principal silversmith during the most fruitful years of his career was William Elliott of Clerkenwell. Elliott (1773-1855) is recorded as the manufacturing silversmith at 25 Compton Street, Clerkenwell. The lack of any substantial information about him and his workshop in no way diminishes the exceptional quality of much of the surviving silver and silver-gilt which bears his mark. These superb vases exemplify how imaginative, elegant and beautifully executed the designs of Elliot’s workshop were and are my Director’s Choice this week. The vases were commissioned by one of the most interesting characters of the 19th century. Pieces bearing the crest, coat-of-arms or more often the signature of Breadalbane rank amongst the finest plate produced in the 19th century.

08 June 2024

In all the years of handling silver these are the finest Victorian wine coasters we have had the pleasure to be the custodians of. With an extraordinarily elaborate border of harvesting bacchic putti, goats and vine branches together with delicately chased leaves, the scale, quality and gauge is unrivalled with of a gross weight of 3,580g, (115 oz 2 dwt). The family’s crest, garter, motto and reverse cypher are set within a scheme of both plain and chased rocaille scrolls. To the underside of each are four casters, an uncommon feature enabling them to be wheeled down the dining table to the next guest. We are proud to present these celebrations of the love of wine that graced the dining tables of the clan Ferguson as this week’s Director Choice.

01 June 2024

It is generally believed that the first evidence of the sniffing of a powdered tobacco was recorded by the Franciscan monk, Ramon Pane, in 1497. Although the most popular form of inhaling tobacco right up until the late 17th century was of course through smoking. By the beginning of the 18th century the fashion for taking snuff had become widespread. Gold boxes have always played a long and important role in fashion, self-promotion, diplomacy and in collecting. Often, they were used as a currency for their monetary value and the status they could embody. Their practical purpose was usually secondary, and they have always been a source of fascination. This Italian eighteen carat gold table snuff box is of such exceptional proportions and its creator the goldsmith Bellezza has spared no expense in the making of his masterpiece. It is lavishly decorated and finished with such jewel like quality that it is my Director’s Choice. We are proud to present this unique triumph of the goldsmith.It is generally believed that the first evidence of the sniffing of a powdered tobacco was recorded by the Franciscan monk, Ramon Pane, in 1497. Although the most popular form of inhaling tobacco right up until the late 17th century was of course through smoking. By the beginning of the 18th century the fashion for taking snuff had become widespread. Gold boxes have always played a long and important role in fashion, self-promotion, diplomacy and in collecting. Often, they were used as a currency for their monetary value and the status they could embody. Their practical purpose was usually secondary, and they have always been a source of fascination. This Italian eighteen carat gold table snuff box is of such exceptional proportions and its creator the goldsmith Bellezza has spared no expense in the making of his masterpiece. It is lavishly decorated and finished with such jewel like quality that it is my Director’s Choice. We are proud to present this unique triumph of the goldsmith.

25 May 2024

When seeking perfection in Neo-classical architecture one need look no further than this magnificent tea and coffee service which I am proud to present as my Directors Choice. With its jewel like finish it mirrors ancient forms to present vessels for the civilised ceremony of taking tea and coffee. Because of its beauty, design and quality this service captured the imagination of one of the great Regency designers.

18 May 2024

One of our most recent acquisitions is the splendid Baron Guernsey Monteith bowl, it has made me focus on our current magnificent collection of vessels made for punch. Our collection dates from 1695 to 1744 and highlights the importance and popularity of this ‘new world’ concoction. Punch remained the tipple of choice for English aristocrats for hundreds of years. The spirits consisted of tea, sugar, citrus and nutmeg and were all expensive ingredients. Lemons were scarce and costly, and became status symbols in Northern Europe, one of the reasons they are found in so many Dutch still life paintings. In the late 17th century London, a three-quart bowl of punch cost the equivalent of half a week's living wage. Commissioning one of these silver vessels was the perfect way to show your education, prosperity and status. My Director's Choice this week focuses on three exceptional punch bowls, each exemplifying the skill, craftsmanship and lengths their owners went to create these table ornaments that served both in function and beauty.

11 May 2024

The genius of Rundell, Bridge and Rundell was their ability to promote display silver as fine art. The large pieces of plate they were producing were pure sculpture. They were clever in protecting their workshops by running all aspects of the process and thus preventing their new and magnificent designs from entering the hands of rival firms such as Green Ward & Green. Rundell were unique in making objects for their showrooms on a speculative basis and were able to promote them by exhibiting silver made for the Prince of Wales’s new service or indeed the famous Shield of Achilles in 1807 and 1821 respectively. They were able to draw on their extensive library and every form of antiquity would have inspired their ever-evolving designs for these splendid table sculptures. This magnificent set of table vases exemplify the genius and perfection that the architect, modeller and silversmith could achieve for the royal retailers and are my Director’s Choice this week.

04 May 2024

Stumbling on such a whimsical menagerie so full of life and character as this group of drinking vessels is what makes this business such a pleasure. Finding so many original, rare forms of novelty Victoriana makes this a truly exciting opportunity for the collector.

27 April 2024

This extraordinary pair of soup tureens, liners and stands exemplify the magnificence of what was the most valuable service in the country. The lavishness and opulence of the cast and applied decoration of patriotic English oak and acorns together with adorned acanthus would have graced the presence of royalty and aristocrats at the Duchess’ residence in Statton Street. The beauty of their design by Edward Hodges Baily and brilliance in execution by Rundell’s workshop make these my Director’s Choice this week.

20 April 2024

These sculptural vessels epitomise the high rocaille style created by Nicholas Sprimont. They also demonstrate the close ties between the modelling of silver and porcelain and the interconnected business relationships between a small group of leading silversmiths working around Compton Street in Soho in the 18th century. Sauceboats of this quality exist in a few museum collections around the world. This jewel-like pair has quality, provenance, and exquisite modelling, making these an easy Director’s Choice.

13 April 2024

As we continue to expand our collection of jewellery at Koopman Rare Art, we endeavour to find rare and wonderful jewels made in the 19th and early 20th century. Jewellery in the 19th century was characterised by opulence, innovation and symbolism, reflecting the social, cultural and technological advancements of the time. The early years were heavily influenced by the neoclassical style, drawing inspirations from ancient Greece and Rome. This is highlighted through the use of cameos and intaglios, and motifs of classical figures reflecting the fascination with ideals of harmony and mythology. Though as the century progressed and the Romantic movement swept across Europe, jewellery craftsmanship was inspired by nature and emotion, with floral motifs and symbols of love becoming more prominent. Gemstones like pearls, sapphires and turquoise were favoured for their delicate colours and organic appeal.

06 April 2024

My choice this week is this little jewel of a tankard. It is perfect in its colour, proportions, and use of ornamentation and cast elements. Finding a Norwegian silver tankard as early as 1650 is incredibly rare. This beautiful example has unusual features, such as its double-eagle thumb piece and three handsome lion sejant feet.

30 March 2024

These sumptuous tureens form part of one of the most famous dinner services that Jean-Baptiste Claude Odiot was commissioned to make amongst other such as the Borghese or Demidoff services. They epitomise the pure essence of the High Empire style with elegant proportions and exquisite detail, they are my director’s choice and we are proud to present their beauty and history.

23 March 2024

The grandeur of the Regency period was never better represented than in the quality, scale, proportions, and masterful workmanship of this monumental pair of candelabra centrepieces that we proudly present as my Director’s Choice this week. A celebration of the fruits of the earth to be enjoyed in the banqueting halls of Casa Palmela in Lisbon, the home of Henrique Teixeira de Sampaio, 1st Conde de Póvoa and Barao de Teixeira. They formed part of one of the most important services ever produced by Paul Storr immediately after his time had finished with the retail firm Rundell Bridge and Rundell. Here Storr truly shows his virtuosity and ability, and no detail is spared given the scale of these masterpieces of the decorative works of art.

16 March 2024

Our continual quest to find the next masterpiece or unearth that lost treasure leads us on the rare occasion to have the fortune of stumbling on something completely unique. This is the first time I have had the pleasure of handling a chocolate jug and not just a single example, but a perfectly formed pair surviving in pristine condition. I have only read about such objects in the past and their presence is something that has only existed in ledgers or inventory records of the royal palaces and aristocratic households. It is easy to make this pair of splendid chocolate jugs my Director’s Choice.

09 March 2024

Currently (7th-14th March), we are exhibiting at TEFAF Maastricht. This week, I want to highlight an exceptional set of cased Tea Caddies; I hope they will give you an idea of the calibre of objects we have brought with us to TEFAF.

02 March 2024

The Warwick Vase, an ancient Roman marble vase with Bacchic ornament was discovered at Hadrian's Villa in Tivoli about 1771 by Gavin Hamilton, a Scottish painter-antiquarian and art dealer in Rome. With John Flaxman and Paul Storr creating the first versions in silver, it was to become England’s Vase, affirming its owner was a connoisseur of the classics and grand tour. These extraordinary royal vessels for wine incorporate the Bacchic masks, vine tendrils, thyrsi, and grape and vine architecture that are wholly inspired by this famous vase. They are my Director’s Choice as their sublime finish and attention to the detail make these royal ewers amongst the finest, I have ever had the pleasure to handle. We will be exhibiting these stunning ewers at this years TEFAF Maastricht which runs from 7th – 14th March.

24 February 2024

With the approach of TEFAF Maastricht 7th - 14th March, I wanted to showcase another one of the highlights we will be exhibiting this year. The celebrated silversmith Paul Storr made this magnificent set of eight salt cellars for the Earl of Grosvenor while working for the Royal retail firm Rundell, Bridge & Rundell.

17 February 2024

With the approach of TEFAF Maastricht 7th - 14th March, I wanted to showcase one of the highlights we will be exhibiting this year. We are on the eternal quest to find perfection and every once in a while, you come across something of such exceptional beauty that it literally takes your breath away. This extraordinary suite of cups and covers leaves the admirer in awe of the technical ability, grace of design, and inspired by the beauty that the royal goldsmith Thomas Heming achieved in the creation of these magnificent objects. I am proud to present these as my choice this week.

09 February 2024

Belonging to the late Rococo, these exquisite English candelabra are far from excessive in their rich decoration. They are the perfect balance of form, fluidity and harmony.

05 February 2024

To celebrate Year of the Dragon, I thought it would be the perfect time to start my weekly choice of object. The world will celebrate Chinese New Year on the 10th and 11 th February. The most famous of the Chinese Zodiac animals, the Dragon is strong and independent and is a great leader, yet they seek support and reassurance from others.

16 January 2024

The first table wine coolers were made in the closing years of the 17th century with the use of the wine cistern slowly being superseded. The need for a single bottle cooler was felt, probably at first on those rare occasions when the master of the great house was dining alone. These were two-handled and vase-shaped having a detachable collar and liner to hold back the ice and to allow for the free insertion of the bottle. Usually made in pairs or occasionally in sets of four, wine coolers were substantial objects, and were intended as much for display as for use. The 19th century saw this vase-shaped form develop with prevailing fashionable details varying in everything from Rococo to Gothic architecture. The difference with Paul Storr, at first with Rundell, Bridge and Rundell from 1807-1819 and after with Storr & Mortimer and other outlets for luxury goods was startling: instead of patrons dictating the type of goods he or she required and what they should look like, Storr determined what the client should buy. The full ornamental value of twisting vine tendrils, spreading shaped leaves and fleshy bunches of grapes and the modelling of such with a Bacchic theme would have been a standard part of an apprentice artisans training from the seventeenth to the nineteenth century. With wonderful architects and artists employed to design new items. The likes of William Theed R.A, Thomas Stothard R.A, John Flaxman, the influences of James "Athenian" Stuart and Edward Hodges Baily were just a few of the great minds helping Paul Storr achieve the wonders that finally graced the table as a wine cooler. We are proud to present a selection of these elegant, superbly detailed and beautiful vessels that graced the tables of the great houses here in England. All bearing that magical goldsmith’s signature of Paul Storr. The Earl of Caledon’s Wine Coolers A Magnificent Pair of George III Wine Coolers London, 1809 Maker's mark of Paul Storr Weight: 232.88 ozs, (7,242g) Height: 9.25in, (23.5cm) Bearing the coats-of-arms of Du Pré Alexander, 2nd Earl of Caledon. These wine coolers in imperial style are of urn shape, with detachable capes and interior liners. The capes with shell, gadroon and palmette borders, the main body half-fluted with a single plain band. The two reeded handles with cast shell and foliate decoration, terminating in lion’s head mask. The coolers resting on four lion’s paw feet raised on an alter pedestal. Each side with the family coat-of-arms and engraved with the family motto, "PER MARE PER TERRAS" The 2nd Earl of Caledon, engraved by Charles Turner from a portrait by Richard Rothwell Du Pré Alexander, 2nd Earl of Caledon KP. (14 December 1777 – 8 April 1839) Styled the Honourable Du Pré Alexander from 1790 to 1800 and Viscount Alexander from 1800 to 1802, was an Irish peer, landlord and colonial administrator, and was the second child and only son of James Alexander, 1st Earl of Caledon He was educated from 1790 to 1796 at Eton College in England and later at Christ Church, Oxford. He was elected Member of Parliament for Newtownards in 1800 and sat in the Irish House of Commons until the Act of Union in 1801. In the latter year, he was appointed High Sheriff of Armagh.[1] He succeeded to the title of Earl of Caledon on the death of his father in 1802 and was elected a Representative Peer for Ireland in 1804. In July 1806 he was appointed Governor of the Cape of Good Hope in what is now South Africa. He was the first governor on the Cape's cession to United Kingdom; the Caledon River and the district Caledon, Western Cape there are named after him. Lord Caledon was not, literally, the first British civil governor of the Cape, having been preceded in that capacity by Lord Macartney and Sir George Yonge, successive holders of the office between the first conquest of the Cape, and its cession back to the Dutch under the terms of the Peace of Amiens of 1802. Rather, Lord Caledon was the first civil governor after the Cape's reconquest from the Dutch by General Sir David Baird in 1806. The question of the relationship between the civil and the military authorities of the colony, personified in Lord Caledon's relationship with the Commander-in-Chief, General Sir Henry Grey, was the most troublesome of the former's period of office as governor, and the issue on which he resigned in June 1811. Less than three years after his departure, in March 1814, an open letter was written defending his record as governor. The writer, Colonel Christopher Bird, Deputy Colonial Secretary at the Cape (subsequently Colonial Secretary), was well qualified to speak, although his partisanship on Lord Caledon's behalf is unconcealed. In another part of the Caledon Papers, Lord Caledon's own appraisal of his governorship of the Cape is to be found. It occurs in the course of a letter which he wrote to the Prime Minister, the 2nd Earl of Liverpool, in 1818 stating his claims to be given a peerage of the United Kingdom: '... The administration of the colonial government during my residence there for a term of four years, was more than usually arduous, in consequence of my being the first civil governor after the capture of the settlement, and from there being no records of a former British government in any of the public offices at The Cape. ... I hope I shall be excused for stating that, upon my own responsibility and under the most embarrassing circumstances, occasioned by the loss of four British frigates which were to have protected the convoy, I detached 2,000 infantry to co-operate with the force from India in the reduction of the Mauritius. In a letter from Lord Minto [Governor General of India] upon that occasion, he acknowledges the public service I rendered, not only as relating to the fall of the Mauritius, but adds that it was to the co-operation I afforded he was indebted for the means of moving against Java. ...'.[2] Lord Caledon married Lady Catherine Yorke, daughter of Philip Yorke, 3rd Earl of Hardwicke and Lady Elizabeth Lindsay, on 16 October 1811 in St. James' Church, Westminster, and had issue: James Du Pre Alexander, 3rd Earl of Caledon (27 July 1812 – 30 June 1855) With this marriage the Caledon family effectively inherited Tyttenhanger House near St Albans, Hertfordshire, which had belonged to the 3rd Earl of Hardwicke's grandmother, Katherine Freeman, the sister and heiress of Sir Henry Pope Blount, 3rd and last Baronet.[2] Sir Henry died in 1757 without issue, leaving his sister Katherine, the wife of Rev. William Freeman, his heir. She left an only daughter, Catherine, who married Charles Yorke, second son of Philip Yorke, 1st Earl of Hardwicke, whose son Philip, 3rd Earl of Hardwicke, on his death in 1834, left four daughters, to the second of whom, Catherine, the wife of the 2nd Earl of Caledon, came the manor of Tyttenhanger. Lord Caledon was invested as a Knight of St Patrick on 20 August 1821 and was appointed Lord Lieutenant of County Tyrone in 1831. He died on 8 April 1839 at Caledon, aged 61, much mourned by his tenants in the model town of Caledon, which he had rebuilt and enlarged so sympathetically. A loyal address from the tenantry issued a few years earlier alludes to his 'acts of liberality, munificence and kindness' and there is plenty of evidence to confirm that this was no mere empty elegy. 'Lord Caledon', wrote Inglis in his book Ireland (1834), 'is all that could be desire – a really good resident country gentleman'.[3] Lady Caledon died on 8 July 1863, having bequeathed Tyttenhanger to her daughter-in-law Jane, with an entail upon her four children and, according to one source, the estate descended to her eldest son James Alexander, 4th Earl of Caledon, who died in 1898. His widow became lady of the manor and held it in trust for her children.[4] Other sources indicate that Tyttenhanger was the home of Lady Jane Van Koughnet, the daughter of the 4th Earl of Caledon, and her husband, Commander E. B. Van Koughnet, until her death in 1941.[5] The house was sold in 1973. References: 1. Stuart, John (1819). Historical Memoirs of The City of Armagh. Newry: Alexander Wilkinson. p. 557. 2. Summary of the Caledon Papers, Public Record Office of Northern Ireland, A. P. W. Malcomson 3. Great Houses of Ireland, Hugh Montgomery-Massingberd and Christopher Simon Sykes (Laurence King, London 1999) 4. A History of the County of Hertford: volume 2, 1908, found at http://www.british-history.ac.uk/report.asp?compid=43299 5. Hertfordshire County Homes, found at http://www.hertfordshire-genealogy.co.uk/data/books/books-3/book-0325-herts-county- homes.htm The Earl of Coventry’s Wine Coolers A Magnificent Set of Four George III Wine Coolers London, 1810 With maker’s mark of Paul Storr Retailed by Rundell, Bridge and Rundell Height: 11 5/8 in. 29.5 cm Weight: 21,894 g, 703 oz 19 dwt Bearing the coat-of-arms of the Earl of Coventry This form of wine cooler is based on the Roman Medici Krater but some of the decoration has been replaced by the splendid cast and applied coats-of-arms of the Earl of Coventry. The lower bodies cast in sections and applied with palm and acanthus spaced with grapes and cornucopias above square bases. The capes with egg and dart rims above applied grapevine. The stippled bodies with applied cast contemporary arms, supporters and coronets. The reeded handles rising from bearded Bacchic masks and backed by large anthemia. The base rims with the Latin signature of Rundell, Bridge & Rundell and numbered 406. The arms are those of Coventry, for George 7th Earl of Coventry 1758-1831, who succeeded to the title in 1809. His father, the 6th Earl, who married one of the Gunning sisters, famous for their beauty, updated Croome Court in Worcestershire with the help of Capability Brown and Robert Adam. It was Brown’s first project, started in 1751 and called by him “his first and most favourite child”. Adam was brought to the house in 1760 and his long gallery is thought to be the first complete example of his work. Both remained friends with the Earl who was a pall bearer at Adam’s funeral. The tapestry room (Gobelins) is now installed in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Baron Roberts Wine Coolers A Pair of 19th Century Regency Wine Coolers By Paul Storr London, 1812 Weight: 9300 g, 299 oz Bearing the coat-of-arms of Baron Roberts The wine coolers on square pedestal feet with urn shaped collets rising to the main krater-shaped bodies. The base of the body with fluting with an ovolo band. The entire bodies stippled with cast and applied coats-of-arms to either side for the Roberts family. The tops of the main body with cast and applied grapes and vines following all the way round and sprouting from the bifurcated vine branch handles. The capes with a cast laurel border, the coolers also with their original silver liners. A Pair of 19th Century George III Wine Cooler on Stands. London, 1819 Maker’s mark of Paul Storr Weight: 367 oz 6 dwt Height: 26.7 cm, 10.5 in The design of this magnificent pair of wine coolers on stands is attributed to Edward Hodges Baily. The wine coolers on circular stands with shell, acanthus and palmette borders. The bases also fluted and rising to a platform with a band of scrolling acanthus. The coolers on four scrolled shell feet with a cast and applied spray of oak leaf and acorn rising up the body of the cooler above the shells. The main bodies fluted and terminating at the collar with a contrasting plain convex band. The reeded handles bound and terminating on the main body with acanthus leaves. The capes with a matching border of shell, acanthus and palmette border to the base. The coolers also with their original silver liners. Literature: For comparison, Paul Storr, 1771-1844: Silversmith and Goldsmith by Norman M. Penzer. A Pair of Geo IV Warwick Vase Wine Coolers London, 1821 Maker’s mark of Paul Storr Weight: 6,740 g, 216 oz 14 dwt Height: 19.5 cm, 7.7 in The Warwick Vase is an ancient Roman marble vase with Bacchic ornament that was discovered at Hadrian's Villa, Tivoli about 1771 by Gavin Hamilton, a Scottish painter-antiquarian and art dealer in Rome, and is now in the Burrell Collection near Glasgow in Scotland. The vase was found in the silt of a marshy pond at the low point of the villa's extensive grounds, where Hamilton had obtained excavation rights and proceeded to drain the area. Hamilton sold the fragments to Sir William Hamilton, British envoy at the court of Naples from whose well-known collection it passed to his nephew George Greville, 2nd Earl of Warwick, where it caused a sensation. Restoration of the Vase The design and much of the ornament is Roman, of the second century CE, but the extent to which the fragments were restored and completed after its discovery, to render it a fit object for a connoisseur's purchase, may be judged from Sir William Hamilton's own remark "I was obliged to cut a block of marble at Carrara to repair it, which has been hollowed out & the fragments fixed on it, by which means the vase is as firm & entire as the day it was made." Needless to say, Sir William did not visit Carrara to hew the block himself. The connoisseur-dealer James Byres's role in shaping the present allure of the Warwick Vase is not generally noted: "The great Vase is nearly finished and I think comes well. I beg'd of Mr. Hamilton to go with me the other day to give his opinion. He approved much of the restoration but thought the female mask copied from that in Piranesi's candelabro ought to be a little retouch'd to give more squareness and character, he's of opinion that the foot ought neither to be fluted nor ornamented but left as it is being antique, and that no ornament ought to be introduced on the body of the vase behind the handles, saying that it would take away from the effect & grouping of the masks. Piranesi is of the same opinion relative to the foot but thinks there is too great an emptyness behind the handles.... It's difficult to say which of these opinions ought to be followed, but I rather lean toward Mr. Hamiltons." Thus it appears James Byres rather than Giovanni Battista Piranesi was put in charge of the vase's restoration and completion. Piranesi made two etchings of the vase as completed, dedicated to Sir William, which were included in his 1778 publication, Vasi, candelabri, cippi..." which secured its reputation and should have added to its market desirability. Sir William apparently hoped to sell it to the British Museum, which had purchased his collection of "Etruscan" vases: "Keep it I cannot, as I shall never have a house big enough for it", he wrote. The Vase at Warwick Castle Disappointed by the British Museum, Hamilton shipped the fully restored vase to his elder nephew, George Greville, 2nd Earl of Warwick, who set it at first on a lawn at Warwick Castle, but with the intention of preserving it from the British climate, he commissioned a special greenhouse for it, fitted, however, with Gothic windows, from a local architect at Warwick, William Eboral: "I built a noble greenhouse, and filled it with beautiful plants. I placed in it a vase, considered as the finest remains of Grecian art extant for size and beauty. "The vase was displayed on a large plinth, which remains with it in the Burrell Collection, where it is also displayed in a courtyard-like setting inside the building, surrounded by miniature fig trees. The vase was widely admired and much visited in the Earl's greenhouse, but he permitted no full-size copies to be made of it, until moulds were made at the special request of Lord Lonsdale, who intended to have a full-size replica cast— in silver. The sculptor William Theed the elder, who was working for the Royal silversmiths Rundell, Bridge & Rundell, was put in charge of the arrangements, but Lord Lonsdale changed his mind, and a project truly of Imperial Russian scale was aborted. (Please see Christopher Hartop’s Royal Goldsmiths: The art of Rundell & Bridge page 117 for a more accurate account). The rich ornament, and the form, which is echoed in sixteenth-century Mannerist vases, combined to give the Warwick Vase great appeal to the nineteenth-century eye: numerous examples in silver and bronze were made, and porcelain versions by Rockingham and Worcester. Theed's moulds were sent to Paris, where two full-size bronze replicas were cast, one now Windsor Castle, the other in the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge. Reduced versions in cast-iron continue to be manufactured as garden ornaments, and in these ways the Warwick Vase took up a place in the visual repertory of classical design. It was even the model for the silver-gilt tennis trophy, the Norman Brookes Challenge Cup won at the Australian Open. On display at the Burrell Collection near Glasgow After it was sold in London in 1978 and purchased by the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the Warwick Vase was declared an object of national importance, and an export license was delayed. Matching funds were raised, and, as it was not of sufficient archaeological value for the British Museum, it found a sympathetic home at the Burrell Collection, Glasgow.

08 November 2023

Man has long been fascinated with the glitter of gold, but its high cost and great softness rendered it impractical for many purposes. Demand for this precious metal drove silversmiths down the ages to devise methods of applying a gold finish to silver. Since ancient times gilding has enhanced silver objects, and items that have undergone that process are referred to as silver gilt, or vermeil in French. There are various methods of gilding, some more dangerous than others. That used in pre-Columbian South America by the Incas was depletion gilding, producing a layer of nearly pure gold on an object of gold alloy by the removal of the other metals from its surface. Another method is overlaying, or the folding of gold leaf, as mentioned in Homer's Odyssey. A third is fire gilding with mercury which involves applying an amalgam of gold and mercury to a silver surface. Heat volatizes the mercury and bonds a strong layer of gold to the silver. Although dangerous for the worker, this method, dating back to the sixth century BC, was used until comparatively recently. It has now been superseded almost entirely by electroplating in which electrolysis is used to coat the surface with gold. This process was finally patented in 1840 by John Wright under the watchful eye of Frederick Elkington the great Victorian retailers of Birmingham. The process of gilding, however, was costly. While in 1664 Samuel Pepys complained that the cost to "fashion", or the making of a piece, had risen to the same level as the raw material itself (both were 5 shillings an ounce), gilding the finished article could cost an additional 3 shillings an ounce. I was fortunate to handle a fine pair of silver-gilt baskets made in London, 1766-7, by Parker and Wakelin in 2007. Documentation in the form of ledgers from their time of making shows that gilding added approximately 25 per cent to the total cost; this was considerably more than commissioning an object in silver yet still less than one produced in gold. By the Middle Ages, European gold was worth ten to twelve times more than silver, but by the eighteenth a nineteenth centuries the price ratio had risen to fifteen to one. Even so, achieving the golden look through gilding became ever more popular. “There was never perhaps an occasion where more plate was brought together in one place “recalled George Fox, Rundells shopman writing in the 1840s on the banquet given by the Corporation of London for the Prince Regent, the Emperor of Russia and the King of Prussia on 18 June 1814. Painting by Luke Clennal. Silver-gilt objects were often used as status symbols, as exemplified by a painting of the Guildhall Banquet held in 1814 for the Prince Regent, the Tsar of Russia, and the King of Prussia. One dinner service is in silver gilt and the other quite intentionally in silver: guests seated with the silver-gilt service are "superior" to those with the silver service. They are also seated in an elevated position over their guests. However, in French silver, many of the important services that have survived to date are entirely in silver gilt. Take for example the early nineteenth-century services for General Count François-Xavier Branicki, or for Count Nikolai Demidoff, or indeed the Borghese service or that made for Madame Mère, the mother of Napoleon. These grand dinner services were nearly all produced by Jean-Baptiste-Claude Odiot and Martin-Guillaume Biennais, both of whom executed imperial commissions. Madame Mère’s inkstand by Jean-Baptiste Claude Odiot, Paris 1809-1819 In this period popularity of silver-gilt items soared on both sides of the Channel, with the English royal goldsmiths Rundell, Bridge & Rundell and master silversmiths Paul Storr and Benjamin Smith leading the way. Their most important patrons were King George III, the Prince Regent (later George IV) and various children of the royal family. Gold, unlike silver, is neither affected by the corrosiveness of salt nor by discoloration by sulphur, nor indeed by the acidity of many of the desserts that were popular at this time. Both silver and silver-gilt dessert services were thus used not merely to denote status but also for a practical reason: after the main course was served on plain silver, the main service was replaced or complemented by the silver-gilt dessert service, sometimes with diners adjourning to a separate room for dessert. Aside from being less expensive than gold, silver-gilt items are lighter in weight and much more durable. Therefore, many delicate objects were made in silver gilt. The nef (cf. the Burghley nef) is a dinner-table ornament or utilitarian vessel in the form of a ship. It dates from the thirteenth to the sixteenth century and was used as a drinking vessel or salt cellar. Indeed, the salt cellar is where silver gilt truly excelled. From medieval times, people recognized the importance of salt as a preservative. Elaborate and grand vessels were made to sit on the table before the master of the house. The expression "right hand man" used today derives from one's position at the table in relation to the salt cellar. The Burghley Nef made in Paris in 1527–28. In Renaissance Europe the cabinets of curiosities (Wunderkammern) of noble households held vast collections in which many wonders from the New World, such as shells, mother of pearl and precious or semi-precious stones, were mounted in silver gilt to set off their beauty and flaunt the knowledge of their owners. Being silver gilt greatly reduced the need to clean and polish them, for gold tarnishes far more slowly than silver. This reduced the risk of an object being damaged, and often gilded items have survived in better condition than their silver counterparts. I am delighted to introduce a beautiful selection of treasures from our collection that highlight the splendour of gilded silver. The collection of silver-gilt objects spans centuries, and each triumph of the decorative arts highlights not only the splendour and richness of gilded silver, but also reflects the socio-economic importance that it has always held. The Grenville-Temple Tazza made in London, 1701 by Anthony Nelme This footed salver which bears the coat-of-arms of Grenville accollé with Leofric quartering Temple would have graced the tables at Stowe House in Buckinghamshire at the time it was made. Its creator, the great Anthony Nelme was free of the Goldsmiths' Company in 1690 was elected to the court of assistants in 1703. He was made fourth warden in 1717 and then second warden in 1722. During the period of Huguenot prominence, Nelme was the leading English-born goldsmiths and was a signatory to the petitions to the Goldsmith Company wardens protesting the presence of the "necessitous strangers" in London. Queen Anne and the leading members of the aristocracy were some of Nelme's patrons. Among most of his important surviving works are a pair of forty-inch alter candlesticks of 1694 at Saint George's Chapel, Windsor (Honour 1971, p. 122), and a pair of pilgrim bottles of 1715 at Chatsworth. Here the gilded surface enhances the elegance and simplicity of an object that one finds in in so many old master still life paintings. Interestingly a salver was defined in 1661 dictionary as "a new peece of wrought plate, broad and flat, with a foot underneath, and is used in giving Beer or other liquid to save the Carpitt or Clothes from drops”. Thomas Lumley-Saunderson was elected without opposition as M.P. for Lincolnshire in 1727 and applied for a peerage as Lord Castleton's heir, but his request was unsuccessful due to King George II's reluctance to grant peerages. He joined the opposition and consistently voted against the government, frequently speaking on matters related to the army and foreign affairs. He was re-elected unopposed for Lincolnshire in 1734 and continued to align with the opposition. In 1737, he was among the Members of the House of Commons who were consulted by the Prince of Wales regarding an application to Parliament for an increase in his allowance. He expressed support and spoke in favour of the increase, which earned him the position of treasurer to the Prince in 1738. In 1740, he succeeded to the earldom of Scarbrough and with these two posts would have needed the most splendid and fashionable plate of the day. Thomas Lumley-Saunderson, 3rd Earl of Scarbrough’s sauce boats, circa 1750 attributed to Nicholas Sprimont These sculptural sauceboats epitomise the high Rococo style popular in mid-18th century London and the close ties between the modelling of silver and porcelain at the time, with the interconnected business relationships between a small group of leading silversmiths working around Compton Street in Soho. A study of Sprimont’s oeuvre in silver shows a close relationship with fellow Huguenot silversmith Paul Crespin (1694-1770), whose workshop was also located in Compton Street. There is compelling evidence to attribute sauceboats of this form to either silversmith. A pair of sauceboats, almost identical to the present lot, with the mark of Crespin, hallmarked for 1746, are in the collection of The Sterling and Francine Clarke Art Institute, Williamstown, Massachusetts. Beth Carver Wees, op. cit., p. 167 also notes that similar sauceboats were also produced by another Huguenot silversmith, Pezé Pilleau, whose son Isaac married a Jane Crespin, possibly Paul's daughter. A further set of four similar sauceboats marked by Crespin were sold at Christie’s, London on 26 March 1975, lot 73. It is thought that either Sprimont worked as a modeller for Crespin, prior to registering his own mark and setting up as an independent silversmith, or that there was an exchange of casts and models between the two, and indeed a wider circle of silversmiths, as shown by a pair of candlesticks by Sprimont of 1745, also in the collection of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, which are identical to a pair by Paul de Lamerie, of 1747, sold Christie's, New York, 14 April 2005, lot 234. The influence of the French master silversmith François-Thomas Germain is evident from a sauceboat, once in the Portuguese Royal Collection, illustrated by Hartop, op. cit., p. 218, from G. Bapst, L'Orfèvrerie Français à la Cour de Portugal au XVIIIe siècle, Paris, 1892, pl. XIV, fig. 50. As Ellenor Alcorn points out, op. cit., p. 162, the links with Crespin are strong. Similar cast coral and shell ornament is found on a small teapot by Crespin of 1740, offered for sale at Christie's London, 3 March 1993, lot 247, now in the Hartman Collection, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Alcorn also notes similar decoration on a Crespin coffee pot of the same year advertised by Spink in the Connoisseur in 1946. Crespin and Sprimont collaborated on the Prince of Wales's Neptune centrepiece. Although the piece is struck with Crespin's mark, the similarity with Sprimont's later work, including the other pieces by him for the Marine Service, has led scholars to include this piece in his list of works. Sprimont was involved with the Chelsea Porcelain Manufactory as early as 1745. He translated a number of his designs for silver into works in porcelain, such as the stand for the Rockingham Sauceboats, which are referred to as 'silver shape' in Ford's auction catalogue for the Chelsea Porcelain Manufactory held in 1755 and discussed by Dr. Bellamy Gardner in his article 'Silvershape in Chelsea Porcelain', published in The Antique Collector, August, 1937, p. 213. Further influence of silver designs on the porcelain of the time is shown by a Derby sauceboat in the Victoria and Albert Museum collection, illustrated by Hartop, op. cit., p. 218. The Rockingham set of four sauceboats and stands suggests Sprimont as the likely maker for the present lot; the sauceboats are similarly unmarked, however the stands are fully marked for Sprimont, London, 1746. A pair was sold in The Exceptional Sale, Christie's London, 22 July 2020, lot 42; a further pair is in the collection of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. The Earl of Grosvenor’s Triton Salt Cellars London, 1810 by Paul Storr. The celebrated Paul Storr was one of the greatest silversmiths and businessmen to ever work in England and from 1807-1819 operated under the royal retailers Rundell, Bridge & Rundell. The reputation that Storr developed during his time was clearly evident and both the Prince Regent and King George III were great admirers and patrons. Of course, the aristocrats and fast-growing nouveau riche wanted to emulate what the king had at his table. The Royal Marine service was started in the 18th century and completed by Storr together with Rundell, Bridge and Rundell in the early 19th century. It is still used today by Charles III for state banquets. With England being an island, there was great symbolism in our navy’s importance and the protection of England by the waters surrounding us. Here with this magnificent set of eight triton salt cellars you see the Earl of Grosvenor following the fashions of the royal palace. The royal collection has a set of 24 with oval bases by Paul Storr also dating to 1810, and one is illustrated in Carlton House: The Past Glories of George IV's Palace, 1991, cat. no. 95, p. 133. How of the moment that the Earl of Grosvenor saw fit to commission this set of eight in the very same year. Perhaps the most iconic gilded object of all recorded pieces in the 19th century is the Shield of Achilles. The spectacular shield is the supreme example of early nineteenth-century English silver and is a triumphant collaboration between the great firm of Rundell and Bridge and the leading designer John Flaxman. “The silver-gilt Shield of Achilles, designed and modelled by one of the greatest English sculptors of the regency, is an outstanding instance of a synthesis of the fine and decorative arts. The designer, John Flaxman was the most illustrious of the Royal Academicians associated with Rundell, Bridge & Rundell ...” (Shirley Bury and Michael Snodin, ‘The Shield of Achilles by John Flaxman R.A., Sotheby’s Art at Auction 1983-4, 1984, pp. 274-83). Flaxman was “the most famous British sculptor and the brightest star in the Rundell & Bridge firmament” (Christopher Hartop, see Literature, p. 104). From 1805 he had been supplying the firm with drawings of figures and friezes which were then employed on various designs for large pieces of silver such as wine coolers and vases. He actually modelled only one piece for the firm, however, the shield of Achilles. Flaxman’s design is an interpretation of the shield wrought for Achilles by the god Hephaestus at the request of Thetis after Achilles lost his armour which he had lent to Patroclus; it having been seized as the spoils of war by Hector. “Then first he formed the immense and solid shield Rich various artifice emblazed the field” Alexander Pope’s translation of the Iliad The Renaissance concept of massive display chargers or shields decorated with scenes celebrating great military triumphs had long been out of fashion but was revived by Philip Rundell and John Bridge by 1810, the year in which Flaxman submitted his first designs for this great project. It was to be another seven years before the design was completed to his satisfaction. In 1817 he made the model for the shield himself which was then cast in plaster. The artist Sir Thomas Lawrence was also presented with a plaster version of the shield. He admired and treasured it to the point he decided to mention Flaxman’s masterpiece in his eulogium to the latter describing it as “that Divine Work, unequalled in the combination of beauty, variety and grandeur, which the genius of Michael Angelo could not have surpassed”. Three or possibly more bronze versions were made and finished by the chaser William Pitts junior and finally in 1819 a silver version was made. It was this shield which was then gilded and sold to George IV in 1821 to form the centrepiece for the buffet of plate at his coronation banquet. Flaxman was initially paid one hundred guineas for ‘4 models and 6 drawings’ and in 1817 he received £200 on account and a further £525 in the following year (John Culme, Important Gold and Silver, sale, Sotheby’s, London, 3rd May 1984, lot 124). Five silver-gilt shields in all were made. The first, mentioned above, which is in the Royal Collection and a further example which was acquired by Frederick Augustus, Duke of York and is now in the collections of the Huntington Library and Art Gallery, San Marino, California; both of these shields are marked for 1821-22. Two further shields both marked for 1822-23 were sold to Hugh Percy, 3rd Duke of Northumberland in 1822 for £2,100 and to William Lowther, 2nd Earl of Lonsdale in 1823 and are in the collections of His Excellency Mohamed Mahdi Altajir and the National Trust at Anglesey Abbey respectively. The present shield which is marked for 1823-24 was sold to Ernst Augustus, Duke of Cumberland and later King of Hanover and for many years its existence was overlooked. The reason for this shield being ‘lost’ springs from the belief that only four were actually made and in part this error must arise from the description by the German Ludwig Schorn of his visit in 1826 to the workshops of Rundell’s: “to the silversmiths Rundell & Bridge who kept a splendid shop not far from St. Paul’s on Ludgate Hill. Here I was shown the shield of Achilles cast in silver and chased after a plaster model which Flaxman had executed to the King’s commission ... the shield has been cast The Shield of Achilles four times in silver for the king, the Duke of York, the Duke of Northumberland and Lord Lonsdale. Gilded the article costs £2000, ungilded £1900” (exhibition catalogue, see Literature, pp. 30-31). This gives the impression that only four shields were made although Schorn must have been looking at the fifth example which is the one sold to the Duke of Cumberland. In 1911 E. Alfred Jones stated that an example had been made for the King of Hanover: “A shield of exactly the same design and of equal size but two years later in date is in the possession of the duke of Cumberland”. Jones must have seen the shield as he makes it clear in the acknowledgements that he was given access to the Hanoverian royal collection. Christopher Hartop realised that there were five shields but did not know of the whereabouts of the Cumberland shield in 2005. The shields were not made to a commission but were a speculative exercise and it would seem that this shield remained in Rundell’s shop on display as a magnificent testament to the supreme skills of their craftsmen and designers. The company, who were excellent self-publicists, would have used the shield as an advertisement to maximum advantage. It was probably sold to the Duke of Cumberland after his accession to the throne of Hanover in 1837 and probably in 1838 as attested by the inscription on the reverse of the shield. The arms must have been engraved after 1839 as they incorporate the Order of St. George of Hanover which was instituted by Ernst Augustus in April 1839. The new Hanoverian monarch acquired massive quantities of plate in 1838 amounting to over 180 kilos and including six thirteen light candelabra and two centrepieces. This great display of plate would have played an important role in the establishment of the new king and the image of splendour that he wished to create for himself. Unlike his brother George IV, he did not acquire plate for the specific occasion of his coronation. The shield appears in a photograph of the Hanoverian royal plate on display in Vienna in 1868. There is no record of the sale of the shield but much of the Hanoverian royal plate was disposed of in 1923 after the death of Crown Prince Ernst Augustus II by the dealers and auctioneers Samuel and Max Glückselig of Vienna and Crichton Brothers of London and it is probable that it was sold at this time. Flaxman in his design adhered closely to the description given by Homer. The design of the shield revolves around the central figure of the Apollo is his chariot of the sun. The frieze, arranged in a succession of groups, depicts the marriage procession and banquet, the quarrel and judicial appeal, the siege and ambuscade and military engagement, the harvest, the vintage, the shepherds defending their herds of cattle from the attack of lions and a Cretan dance. The great stream of the ocean is represented by the surrounding border. Flaxman’s drawings for the shield are in the collections of the British Museum and what is believed to be the original cast for the shield is in the Sir John Soane Museum, London. Allan Cunningham (The Lives of the most eminent British Painters, Sculptors, and Architects, 1833, vol. III) suggested that Flaxman used a translation of the Iliad when working on his design although this was contradicted by Maria Denman, Flaxman’s sister-in-law, who insisted that he had worked from the original Greek text. Hancocks at the Viena Exhibition 1873 The final piece that we present from our collection of silver-gilt objects is pure sculpture enhanced by the beauty of its gilding. Given how extraordinary this piece is in its nature, a complete unique commission that explores every aspect of craftmanship, design and execution of the goldsmith, it is most likely that piece formed part of Hancock’s display at the 1873 Vienna exhibition. Likely candidates for the modelling and design who worked closely with the firm Hancock & Co are: Raffaelle Monti (1818-1881) The son of the sculptor Gaetano Matteo Monti (1776-1847) of Ravenna and Milan, was something of a prodigy. In his late teens, when he was studying under his father and the sculptor Pompeo Marchesi (1790-1858), a former pupil of Canova, at the Academy of Fine Arts of Brera, Milan, he won several prizes including the Great Gold Medal for his group, 'Alexander Taming Bucephalus.' In 1838, having completed another colossal project, 'Ajax defending the body of Patroculus,' he was invited to go to Vienna to produce various busts for the Imperial family. Monti's sudden appearance as a widely known celebrity sculptor in the United Kingdom coincided with the display of his work in London at the Great Exhibition of 1851. Before that he had been known in England to only a select group of wealthy patrons, for one of whom, William Cavendish, 6th Duke of Devonshire (1790-1858), he had created in 1847 his celebrated 'Veiled Vestal. Henry Hugh Armstead RA (1828 – 1905) Henry Hugh Armstead was born in London in 1828 and received his earliest education in the workshop of his father John, a heraldic chaser. He studied at the Government School of Design at Somerset House from the age of thirteen before attending two privately-run drawing schools. Armstead was employed by the silversmiths Hunt and Roskell and Hancock &Co while at the same time working in the studio of sculptor Edward Hodges Baily and studying at the Royal Academy Schools. Until around 1863 he concentrated on metalwork, although the lack of recognition he received in this medium led him to turn to sculpture. After his sculptural work was noticed by the Gothic Revival architect George Gilbert Scott, Armstead was employed to create relief panels and other sculptural decorations for buildings including the Palace of Westminster, the Albert Memorial and the Colonial Office (now the Foreign and Commonwealth Office) on Whitehall. His sculpture anticipates the later New Sculpture movement which broadly rejected classicism in favour of realism. Armstead, who also produced numerous book and magazine illustrations, was elected as a Royal Academician in 1879 (his Diploma Work was a marble relief, The Ever-Reigning Queen). He took an active role in the work of the academy, teaching in the schools for many years and placing the sculpture in many RA exhibitions. He died at his house in London, in 1905. Both Armstead and Monti together with the architect Owen Jones also produced the ‘Tennyson Vase’ for the Paris 1867 Exhibition for Hancock’s which was purchased at the Exhibition by Napoleon III. The Goodwood Cup of 1866 and Armstead was again involved in the modelling of a Hancock presentation centrepiece commissioned by the Engineers of the Indian Service to the Royal Engineers in the same year as this magnificent ewer in the Vienna Exhibition 1873. An Exceptional Victorian Ewer 1873 by Charles Frederick Hancocks

07 August 2023