BACK TO LIST

BACK TO LIST

The Genius of Piranesi and his Influence on English Silver

Giovanni Battista Piranesi (1720–1778)

One of the greatest printmakers of the eighteenth century, Piranesi always considered himself an architect. The son of a stonemason and master builder, he received practical training in structural and hydraulic engineering from a maternal uncle who was employed by the Venetian waterworks, while his brother, a Carthusian monk, fired the aspiring architect with enthusiasm for the history and achievements of the ancient Romans. Piranesi also received a thorough background in perspective construction and stage design. Although he had limited success in attracting architectural commissions, this diverse training served him well in the profession that would establish his fame.

Whether or not Piranesi studied printmaking in Venice, it is certain that soon after his arrival in Rome in 1740, he apprenticed himself briefly to Giuseppe Vasi, the foremost producer of the etched views of Rome that supplied pilgrims, scholars, artists, and tourists with a lasting souvenir of their visit. Quickly mastering the medium of etching, Piranesi found in it an outlet for all his interests, from designing fantastic complexes of buildings that could exist only in dreams, to reconstructing in painstaking detail the aqueduct system of the ancient Romans. The knowledge of ancient building methods demonstrated by Piranesi’s archaeological prints allowed him to make a name for himself as an antiquarian—his Antichità Romane of 1756 won him election to the Society of Antiquarians of London. Etching also provided Piranesi with a livelihood, allowing him to turn one of his favourite activities, drawing the ancient and modern buildings of Rome, into a lucrative source of income. By 1747, Piranesi had begun the work for which he is best known, the Vedute di Roma (Views of Rome), and he continued to produce plates for the series until the year of his death in 1778. Piranesi’s popular Vedute, which eclipsed earlier views of Roman landmarks through their dynamic compositions, bold lighting effects, and dramatic presentation, shaped European conceptions to such an extent that Goethe, who had come to know Rome through Piranesi’s prints, was somewhat disappointed on his first encounter with the real thing. Piranesi’s willingness to embrace the profession of printmaking was conditioned by his ties to Venice, the only city in eighteenth-century Italy where the greatest artists turned their hands to etching. Piranesi returned to his native city twice in the mid-1740s, the very years in which Canaletto was producing his luminous etched views of Venice and Tiepolo was at work on his novel series of etchings, the Scherzi and the Capricci—long recognized as an inspiration for the sketchy improvisation of Piranesi’s Grotteschi. The series of labyrinthine prison interiors, the Carceri, was also created soon after Piranesi’s encounter with the lively printmaking scene in Venice. In these prints, Piranesi explored the possibilities of perspective and spatial illusion while pushing the medium of etching to its limits.

Given his admiration for Rome and his contentious nature, Piranesi could hardly refrain from entering the debate at mid-century over the relative merits of Greek and Roman art. Here, too, etching served him well as a means of supporting his arguments. His Delle magnificenza ed architettura de’ Romani of 1761 advanced the view, shared by other scholars, that the Romans had learned not from the Greeks—as British and French scholars had begun to argue—but from the earlier inhabitants of Italy, the Etruscans. Piranesi used his knowledge of ancient engineering accomplishments to defend the creative genius of the Romans but devoted even more space to a celebration of the richness and variety of Roman ornament.

While Piranesi championed the art of Rome, he was not indifferent to the charms of Greek art, nor to that of the Egyptians, as is evident from his fanciful design for an Egyptian fireplace or his decorative scheme for the walls of the Caffè degli Inglesi, the British cafe located in the Piazza di Spagna. In his preface to the Diverse maniere d’adornare i cammini of 1769, which includes both of these etched plates along with designs in the Etruscan, Greek, Roman, and even Rococo styles, Piranesi argued for the complete freedom of the architect or designer to draw on models from every time and place as an inspiration for his own inventions. Piranesi’s etchings of his eclectic mantelpiece and furniture designs circulated throughout Europe, influencing decorative trends, and even functioned as a sales catalogue to advertise the objects he fashioned from ancient remains. Some of the fireplace designs included in the Diverse maniere were actually executed under Piranesi’s direction, utilizing antique fragments discovered in recent excavations. The restoration of such fragmentary remains, a process that ranged from simply providing an ancient Roman vase with a suitable antique base to such elaborate assemblages as the Newdigate candelabrum, became a new business for Piranesi.

Piranesi’s unique opportunity to exercise his creative genius on a monumental scale occurred during the reign of the Venetian pope Clement XIII (1758–69), when the papal nephew, Cardinal Rezzonico, assigned him two major architectural projects. Although Piranesi’s elaborate designs for the apse of the Lateran Basilica were never realized, he was able to apply his original conception of ornament to the renovation of the church of the Knights of Malta on the Aventine, Santa Maria del Priorato, which included an impressive ceremonial piazza enclosed by obelisks and trophies.

It seems that the artist’s tireless devotion to his work and his identification with the grandeur of Rome never flagged, for on the day of his death, Piranesi reportedly refused to rest saying that repose was unworthy of a citizen of Rome, he spent his last hours busy among his drawings and copperplates.

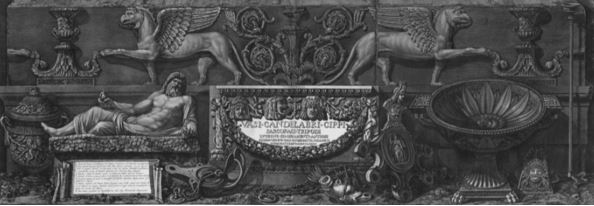

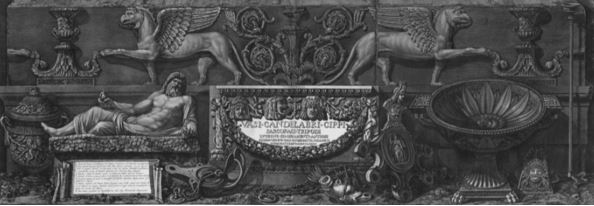

Vasi, Candelabri, Cippi, Sarcofagi, Tripodi, Lucerne, Ed Ornamenti Antichi Disegn Ed Inc Dal Cav. Gio.

This print is from a series of etchings made by Piranesi documenting antiquities excavated in Italy in the 18th century many of which had passed through Piranesi’s restoration workshop which he had established in Rome. The plates that Piranesi produced included text with information on the circumstances of discovery of each object and their contemporary location. The prints also bore dedications to Piranesi’s patrons and influential friends. This etching was dedicated to His Excellency, Signor General Schouvaloff, the Russian connoisseur, although the text is missing from this example. The etchings were made between 1768 and 1778 when they were issued as separate plates. However, in 1778 they were assembled and published as a collection in two volumes under the title Vasi, Candelabri, Cippi, Sarcofagi, Tripodi, Lucerne Ed Ornamenti Antichi.

The vase in this etching is known as the Medici vase and at the time of publication was in the Galleria delle Statue in the Villa Medici. It is now in the Uffizi Gallery in Florence. It is believed to have been made about AD 50 to 100 and shows in carved relief the sacrifice of Iphigenia, daughter of Agamemnon, King of Mycenae. Iphigenia is flanked by the figures of Ulysses and Agamemnon.

Alongside Piranesi’s other publications, the series of prints published in Vasi…had a major influence on the development of the neo-classical style and served as source material for many architects and designers. In particular Piranesi was well known among wealthy English visitors to Rome who were frequent visitors to his workshop and who used the Grand Tour to add to their collections of antiquities.

His prints not only showcased his technical mastery but also revolutionized the understanding and appreciation of architectural and decorative motifs from ancient civilizations.

Piranesi's prints primarily focused on architectural subjects, particularly the ruins of ancient Rome. His meticulous attention to detail and his ability to capture the grandeur and magnificence of these architectural remnants made his prints highly sought after by collectors, architects, and designers of the time.

These prints were not only accurate representations but also imaginative interpretations of ancient Roman structures. Piranesi employed dramatic lighting, exaggerated perspectives, and intricate detailing to create a sense of awe and monumentality in his prints.

The "Views of Rome" series, with its exploration of ancient architectural forms, had a significant impact on the decorative arts. It influenced the Neoclassical movement, which emerged in the late 18th century and sought to revive the aesthetics of ancient Greece and Rome. The prints provided a rich source of inspiration for architects, interior designers, and craftsmen who sought to incorporate classical motifs into their creations. The grandeur and richness of Piranesi's prints served as a reference for the scale, proportion, and ornamentation of decorative elements.

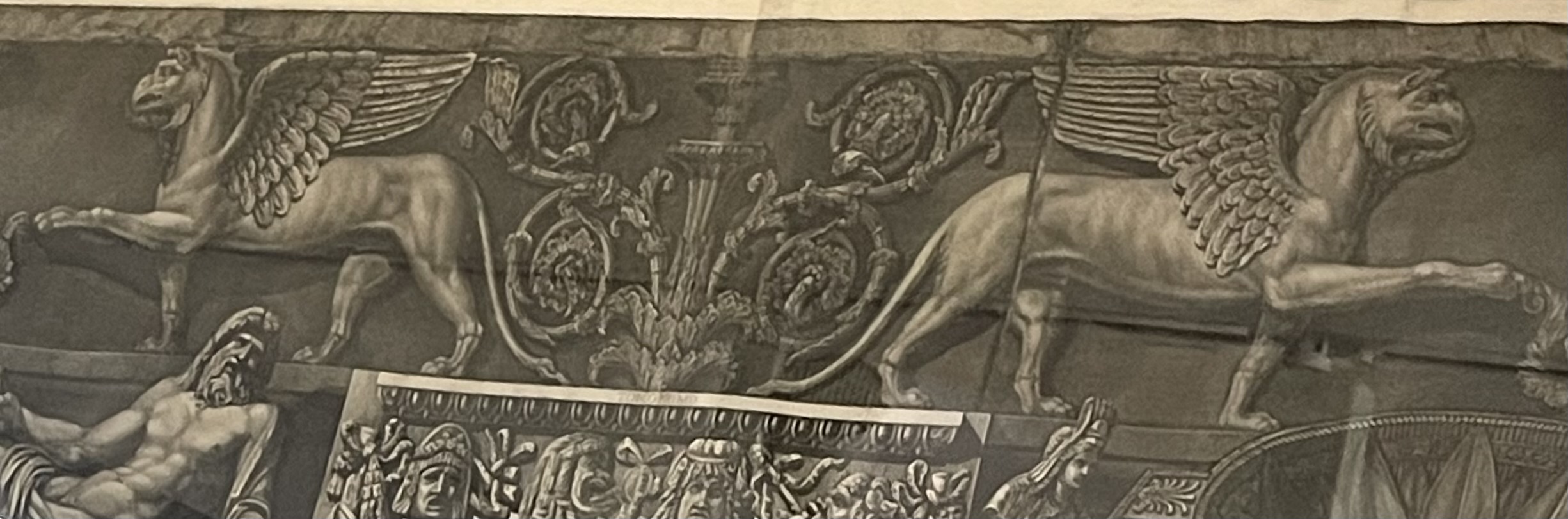

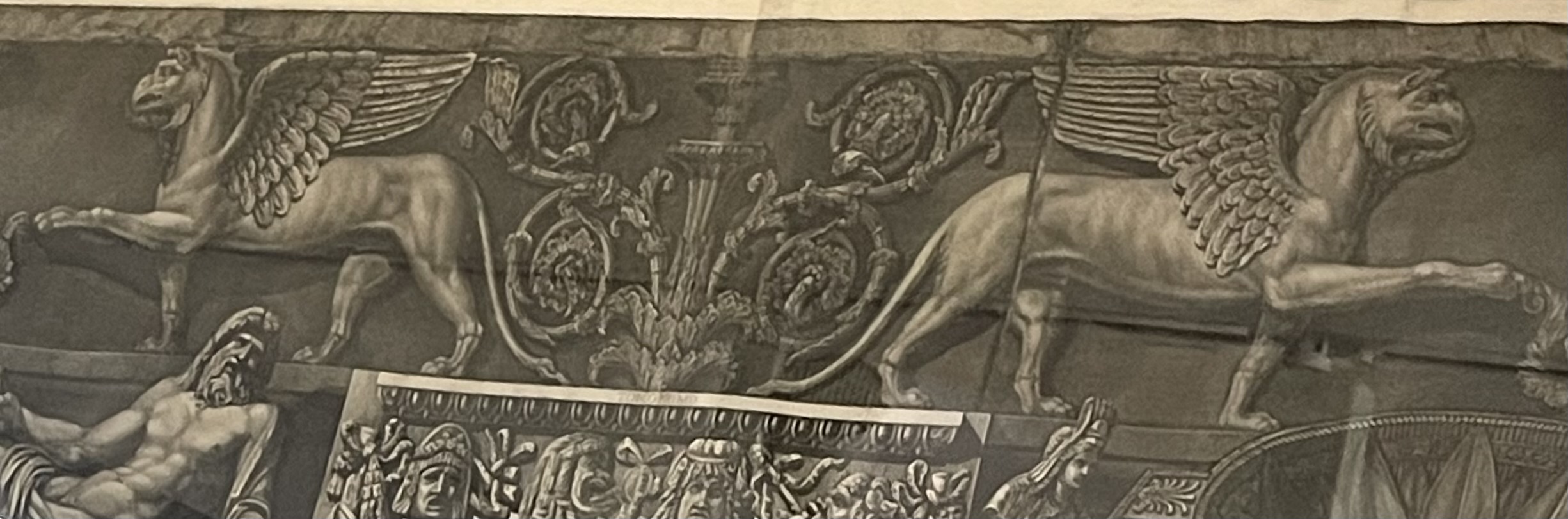

An imaginary view showing examples of ancient Roman decorative styles.

The intricate details and decorative motifs found in his prints were often adapted and incorporated into the design of furniture, textiles, ceramics, and other decorative objects. The elaborate ornamentation, such as foliate motifs, mythical creatures, and architectural elements, became popular decorative motifs in the decorative arts of the time.

Furthermore, Piranesi's prints played a crucial role in shaping the perception and understanding of ancient architecture. His interpretations of ancient Roman ruins presented a romanticized and idealized vision of the past. This romantic notion of antiquity, influenced by Piranesi's prints, permeated the decorative arts, as well as literature and visual arts of the time.

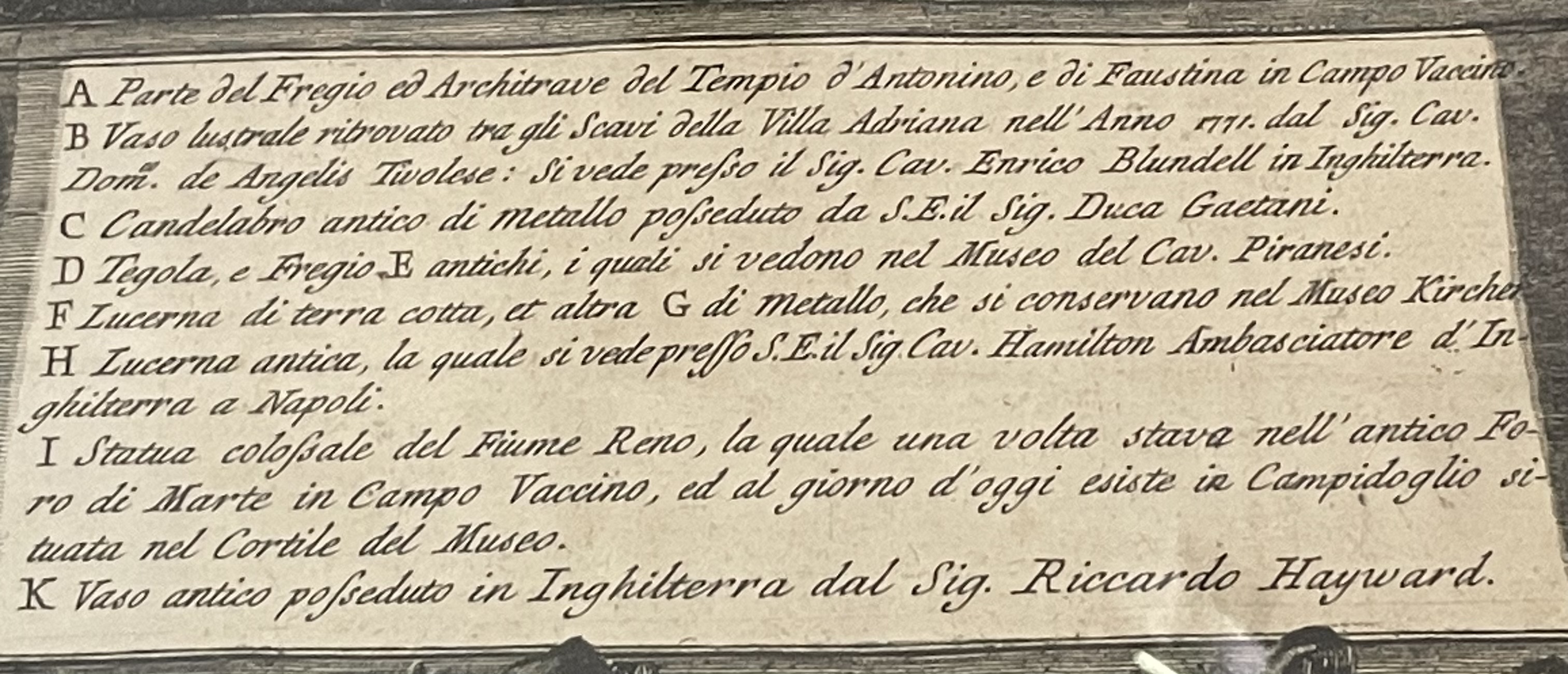

Vasi, Candelabri, Cippi, Sarcofagi, Tripodi, Lucerne, Ed Ornamenti Antichi Disegn Ed Inc Dal Cav. Gio. Batta. Piranesi, pubblicati l’anno MDCCLXXIIX.

A. Part of the Frieze and Architrave of the Temple of Antonino, and of Faustina in Campo Vaccine

B. Lustral vase found in the excavations of Villa Adriana in the year m. by Mr. Cav. Dom. de Angelis Tivolese: It can be seen with Mr. Cav. Henry Blundell in England.

C. Ancient metal candlestick owned by His Excellency Duke Gaetani.

D. Tile, and Frieze E. Ancient, which can be seen in the Museo del Cav. Piranesi.

F. Lantern of terracotta, et al & metal, which are conserved in the Kircher Museum

H. Ancient Lantern, which can be seen by His Excellency Mr. Cav. Hamilton Ambassador of England in Naples.

I. Colossal statue of the river Reno, which once stood in the ancient Foro di Marte in Campo Vaccino, and nowadays it exists in Campidoglio, located in the courtyard of the museum.

K. Ancient vase owned in England by Mr. Riccardo Hayward.

This last group of plates had a huge influence on the decorative arts and in particular silver items produced in the late 18th and early 19th century. Many of the treasures produced bore a direct link to the items found in the prints. Here are a few examples, currently in the Koopman Rare Art Collection that illustrate the influence of Piranesi:

Koopman Rare Art Collection

by Paul Storr

London, 1816

Weight: 51 oz. (1617gr.)

Height: 7 5/8 in. (19.4cm.)

Sugar Urns with classical urn form cast with bands of scrolling foliage, serpent hoop handles, leaf and dart base rims, bud finials, the rims engraved with 1817 presentation inscription, fully marked and with stamped number 853.

The inscription reads, "The Gift of Maria F. Heathcote to Thomas Freeman Heathcote 1817."

The source of the design for these sugar vases is a Roman urn in the celebrated antique sculpture collection of the 1st Marquess of Lansdowne, identified by David Udy in Piranesi's Vasi, the English Silversmith and his Patrons, Burlington Magazine, December 1978, p. 837, fig. 55-57. Unlike the Warwick Vase, which had been popularized by Piranesi's engravings of the Eighteenth Century, the Lansdowne urn apparently was reproduced directly in silver before John Duit engraved it around 1813. The design in silver is attributed to the sculptor John Flaxman, who used a variation of the urn in his tomb monument for Sir Thomas Burrell in 1796. Flaxman became Rundell's most important designer around the time the firm became Royal Goldsmiths in 1804.

Many examples are known, including a set of eight by Benjamin and James Smith, 1808, in the Royal Collection. A set of four by Paul Storr, 1816-17, with the crest of the Dukes of Norfolk, is in the Jerome and Rita Gans collection at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts (cat. no. 45).

Koopman Rare Art Collection

London in 1821

Made by Paul Storr

Weight: 172 oz 5 dwt, 5361.5 g

Length over handles: 14½in., 36.8 cm

The Warwick vase

The Warwick Vase, an ancient Roman marble vase with Bacchic ornament that was discovered at Hadrian's Villa, Tivoli about 1771 by Gavin Hamilton, a Scottish painter-antiquarian and art dealer in Rome, and is now in the Burrell Collection near Glasgow in Scotland.

The vase was found in the silt of a marshy pond at the low point of the villa's extensive grounds, where Hamilton had obtained excavation rights and proceeded to drain the area. Hamilton sold the fragments to Sir William Hamilton, British envoy at the court of Naples from whose well-known collection it passed to his nephew George Greville, 2nd Earl of Warwick, where it caused a sensation.

Koopman Rare Art Collection

London, 1821

Maker’s mark of Paul Storr

Weight: 6,740 g

Height: 19.5 cm, 7.6 in

Width: 22 cm, 8.6 in

The Victoria and Albert Museum collection formerly with Koopman Rare Art

The Hamilton-Beckford Candlesticks

The Hamilton-Beckford Candlesticks

A highly important pair of George III silver-gilt candlesticks after a roman 1st century bronze lampstand

Mark of Charles Aldridge, London, 1787

Each on three matted claw feet with fluted knees above supporting a broad detachable circular plate chased with palm foliage border and inner bands of arcading and alternate panels of differing formal foliage, the detachable fluted stem rising from fluted plinth and of shaped square section, the detachable baluster upper part of the stem and vase-shaped socket chased with further bands of fluting and varying foliage, the detachable circular wax-pan with fluted and ovolo bands, fully marked on lower plates, part-marked on reverse of sockets and on wax-pans

21 3/8 in. (54.3 cm.) high

85 oz. 10 dwt. (2,020 gr.) (2)

Provenance:

William Beckford, MAGNIFICENT EFFECTS AT FONTHILL ABBEY, WILTS; Christie's, 8-17 October 1822 (sale cancelled), either Lot 44 or 45:

44. A PAIR of CANDELABRA of SILVER CHASED and GILT, supported on feet shaped as Lizards

These superb pieces of Plate are truly in classical taste, being executed from the design of a candelabrum found at HERCULANEUM

45. A PAIR of DITTO

William Beckford, The Unique and Splendid effects of Fonthill Abbey; the extensive assemblage of costly and interesting property, which adorns this magnificent structure; Phillips, 23 September-22 October, 1823, either lot 1544 or 1545, with almost identical descriptions and footnote to those in the Christie's catalogue above, located in The Grand (Damask) Drawing Room, No. 24 and sold as one lot for £105.15 to Broadway.

One pair of the two above:

Richard Plantagenet Temple-Nugent-Brydges-Chandos-Grenville, 2nd Duke of Buckingham (1823-1889).

The contents of STOWE HOUSE, near Buckingham, Christie's 15 August-30 September, 1848, lot 783, under the heading GILT

783. A pair of very elegant candelabra, on tripod feet-after those from Herculaneum-from Fonthill 86 ozs. (£98.18s to ?Nathan Jnr.).

Literatue:

M. Snodin and M. Baker, 'William Beckford's Silver II,' The Burlington Magazine, December, 1980, p. 827, under the heading 'English Silver probably or certainly contemporary', no. E3 where the buyer at the Stowe sale is given as S. Peto, M.P.

Related literature:

The Roman original (British Museum Reg.1772.3-4.59) is discussed in:

P. F. d'Hancarville. MS Catalogue des antiquités recueillies, depuis l'an 1764 jusque vers le milieu de l'année 1776 par Mr. Le Chevalier Guillaume Hamilton, acquises par Acte du Parlement en 1772 et maintenant déposéés dans le Muséum Britannique, London 1778, vol. 1, p. 301A.

E. Hawkins, MS Catalogue of the Bronzes in the British Museum, vol. III, p. 166.

D. Bailey, et al, A Catalogue of the Lamps in the British Museum, London, 1996, vol. IV, pp. 91-2, no. Q. 3867, pls. 102 and 103 (schematic drawing).

D'Hancerville (op. cit.) says, in translation, of the original Roman lampstand, which he calls a candelabrum 'close to six foot high', that 'there does not exist at Herculanum [sic] any other as beautiful, nor one which is more perfectly conserved.' This is included in a list in two volumes of the first collection of antiquities formed by Sir William Hamilton, envoy to the Court of Naples from 1764-1800, which was sold to the newly established British Museum following an act of Parliament in 1772 to raise the £8,400 necessary for the purchase.

SPECIAL NOTICE

Sir William Hamilton (1730-1803)

Sir William was a passionate collector of antiquities but also one who 'took seriously his part in the traditional role of the enlightened British aristocracy as patrons of the arts and as promoters of good taste in contemporary manufacture. The sale of the first collection to the British Museum in 1772 was more than a mere financial transaction, for it formed part of a life long mission to raise British, indeed European consciousness in what are now called the decorative arts.' (I. Jenkins " 'Contemporary Minds' Sir William Hamilton's affair with Antiquity", in the exhibition catalogue, Vases and Volcanoes, London, 1996, p. 59). Apart from his collections of Greek and Roman vases, cameos and bronzes Sir William also owned, at least for a short time, the celebrated Portland and Warwick Vases.

He applied for his official position in Naples largely in the hope that it would be beneficial for his wife, Catherine's health. While there they naturally played host to a stream of wealthy and artistic visitors from across Europe which included Mozart and Goethe as well as his second cousin, William Beckford in 1780 and, shortly before Lady Hamilton's death, again in the summer of 1782. A year after Hamilton's return to England in 1799 he, his second wife, Emma and Admiral Lord Nelson spent Christmas as Beckford's guests at Fonthill. Only the St. Michael Gallery had been completed but the effect must have been breathtaking, 'illuminated', as it was, 'with a grand display of wax lights, on candlesticks and candelabras of massive silver-gilt exhibiting a scene at once strikingly splendid and awfully magnificent' (The Gentleman's Magazine, LXXI, p.298).

Charles Aldridge, the Silversmith (w. 1766-1793)

Normally one would expect the silversmith to use a print source for the design of such unusual objects and several illustrations of Roman lampstands from the second half of the 18th century are known, most notably those that appear in the last of eight volumes of Le Antichitá di Ercolano Esposte, Naples, 1757-92. Indeed, a generation after these candlesticks were made, a pair of ormolu torchéres, now in the Royal collection, were supplied to the Prince Regent. They are described in Rundell's bill of 1811 as being 'after those found in the ruins of Herculaneum' and are based on two images illustrated in this important work (pl. LXXI, the base on p. 77, the socket on p. 92; the Regency torchéres are illustrated in the exhibition catalogue, Carlton House, The Past Glories of George IV's Palace, London, 1991-2 p. 91, no. 43). However, the present candlesticks appear to be based directly on the original Roman bronze lampstand which was available of course as a prototype for study at the British Museum in London.

The silversmith Charles Aldridge was apprenticed to Edward Aldridge, presumed to be his uncle, in 1758. He entered his first mark in partnership with Henry Green in 1775 and a second mark alone in 1786. He has followed faithfully the ornament of the Roman original in producing these candlesticks, which are almost exactly a third of the size of the prototype. Allowing for the change of use to a candlestick, the construction with detachable tripod foot, circular plate, distinctive fluted and fourfold stem of cross-shape section and detachable crater-shaped top also follows that of the Hamilton lampstand. The main variations are in the feet that have metamorphosed from lions' paws to lizards' claws and their profile which has been altered, presumably because of the lighter load they have to carry in the 18th century version. In addition an extra baluster has been removed beneath the socket and the flat top of the original has been replaced by a detachable nozzle to reflect the change of function.

Charles Aldridge is not particularly noted for the originality of his designs. Much more typical of his work is the teapot he made with Henry Green for William Beckford in 1782 now at Brodick Castle (T. Schroder, et al, Beckford and Hamilton Silver from Brodick Castle, London, 1980, no. B11). It is also of interest that the maker James Aldridge who produced so many of the most imaginative mounted pieces for Beckford from circa 1815-1823 was apprenticed, and surely related, to Charles Aldridge.

William Beckford (1760-1844)

William Beckford and the silver he ordered has been studied in great detail by Michael Snodin and Malcolm Baker (op. cit.) and the former in 'William Beckford and Metalwork' in the exhibition catalogue William Beckford 1760-1844, An Eye for the Magnificent, New York, 2001, pp. 203-215. His early purchases tend to be standard if sometimes exceptionally well-designed examples of domestic silver which he seems frequently to have taken with him on his extensive travels. While Beckford was mainly in Lisbon in 1787 it is known that a considerable amount of furnishing was underway at Fonthill House, later known as Fonthill Splendens, that summer being mainly designed by the architect John Soane (William Beckford, 1760-1844, op. cit. p.60).

It seems reasonable to assume that Beckford, given the extraordinary originality of his later silver purchases, specially commissioned these remarkable candlesticks rather than acquiring them second hand. Even without the Beckford connection these candlesticks are of exceptional interest. They are based directly on an identifiable object sold with the intention of providing prototypes to the artists and artisans of his day, by Sir William Hamilton in 1772 to the British Museum where it remains.

One of the greatest printmakers of the eighteenth century, Piranesi always considered himself an architect. The son of a stonemason and master builder, he received practical training in structural and hydraulic engineering from a maternal uncle who was employed by the Venetian waterworks, while his brother, a Carthusian monk, fired the aspiring architect with enthusiasm for the history and achievements of the ancient Romans. Piranesi also received a thorough background in perspective construction and stage design. Although he had limited success in attracting architectural commissions, this diverse training served him well in the profession that would establish his fame.

Whether or not Piranesi studied printmaking in Venice, it is certain that soon after his arrival in Rome in 1740, he apprenticed himself briefly to Giuseppe Vasi, the foremost producer of the etched views of Rome that supplied pilgrims, scholars, artists, and tourists with a lasting souvenir of their visit. Quickly mastering the medium of etching, Piranesi found in it an outlet for all his interests, from designing fantastic complexes of buildings that could exist only in dreams, to reconstructing in painstaking detail the aqueduct system of the ancient Romans. The knowledge of ancient building methods demonstrated by Piranesi’s archaeological prints allowed him to make a name for himself as an antiquarian—his Antichità Romane of 1756 won him election to the Society of Antiquarians of London. Etching also provided Piranesi with a livelihood, allowing him to turn one of his favourite activities, drawing the ancient and modern buildings of Rome, into a lucrative source of income. By 1747, Piranesi had begun the work for which he is best known, the Vedute di Roma (Views of Rome), and he continued to produce plates for the series until the year of his death in 1778. Piranesi’s popular Vedute, which eclipsed earlier views of Roman landmarks through their dynamic compositions, bold lighting effects, and dramatic presentation, shaped European conceptions to such an extent that Goethe, who had come to know Rome through Piranesi’s prints, was somewhat disappointed on his first encounter with the real thing. Piranesi’s willingness to embrace the profession of printmaking was conditioned by his ties to Venice, the only city in eighteenth-century Italy where the greatest artists turned their hands to etching. Piranesi returned to his native city twice in the mid-1740s, the very years in which Canaletto was producing his luminous etched views of Venice and Tiepolo was at work on his novel series of etchings, the Scherzi and the Capricci—long recognized as an inspiration for the sketchy improvisation of Piranesi’s Grotteschi. The series of labyrinthine prison interiors, the Carceri, was also created soon after Piranesi’s encounter with the lively printmaking scene in Venice. In these prints, Piranesi explored the possibilities of perspective and spatial illusion while pushing the medium of etching to its limits.

Given his admiration for Rome and his contentious nature, Piranesi could hardly refrain from entering the debate at mid-century over the relative merits of Greek and Roman art. Here, too, etching served him well as a means of supporting his arguments. His Delle magnificenza ed architettura de’ Romani of 1761 advanced the view, shared by other scholars, that the Romans had learned not from the Greeks—as British and French scholars had begun to argue—but from the earlier inhabitants of Italy, the Etruscans. Piranesi used his knowledge of ancient engineering accomplishments to defend the creative genius of the Romans but devoted even more space to a celebration of the richness and variety of Roman ornament.

While Piranesi championed the art of Rome, he was not indifferent to the charms of Greek art, nor to that of the Egyptians, as is evident from his fanciful design for an Egyptian fireplace or his decorative scheme for the walls of the Caffè degli Inglesi, the British cafe located in the Piazza di Spagna. In his preface to the Diverse maniere d’adornare i cammini of 1769, which includes both of these etched plates along with designs in the Etruscan, Greek, Roman, and even Rococo styles, Piranesi argued for the complete freedom of the architect or designer to draw on models from every time and place as an inspiration for his own inventions. Piranesi’s etchings of his eclectic mantelpiece and furniture designs circulated throughout Europe, influencing decorative trends, and even functioned as a sales catalogue to advertise the objects he fashioned from ancient remains. Some of the fireplace designs included in the Diverse maniere were actually executed under Piranesi’s direction, utilizing antique fragments discovered in recent excavations. The restoration of such fragmentary remains, a process that ranged from simply providing an ancient Roman vase with a suitable antique base to such elaborate assemblages as the Newdigate candelabrum, became a new business for Piranesi.

Piranesi’s unique opportunity to exercise his creative genius on a monumental scale occurred during the reign of the Venetian pope Clement XIII (1758–69), when the papal nephew, Cardinal Rezzonico, assigned him two major architectural projects. Although Piranesi’s elaborate designs for the apse of the Lateran Basilica were never realized, he was able to apply his original conception of ornament to the renovation of the church of the Knights of Malta on the Aventine, Santa Maria del Priorato, which included an impressive ceremonial piazza enclosed by obelisks and trophies.

It seems that the artist’s tireless devotion to his work and his identification with the grandeur of Rome never flagged, for on the day of his death, Piranesi reportedly refused to rest saying that repose was unworthy of a citizen of Rome, he spent his last hours busy among his drawings and copperplates.

Vasi, Candelabri, Cippi, Sarcofagi, Tripodi, Lucerne, Ed Ornamenti Antichi Disegn Ed Inc Dal Cav. Gio.

This print is from a series of etchings made by Piranesi documenting antiquities excavated in Italy in the 18th century many of which had passed through Piranesi’s restoration workshop which he had established in Rome. The plates that Piranesi produced included text with information on the circumstances of discovery of each object and their contemporary location. The prints also bore dedications to Piranesi’s patrons and influential friends. This etching was dedicated to His Excellency, Signor General Schouvaloff, the Russian connoisseur, although the text is missing from this example. The etchings were made between 1768 and 1778 when they were issued as separate plates. However, in 1778 they were assembled and published as a collection in two volumes under the title Vasi, Candelabri, Cippi, Sarcofagi, Tripodi, Lucerne Ed Ornamenti Antichi.

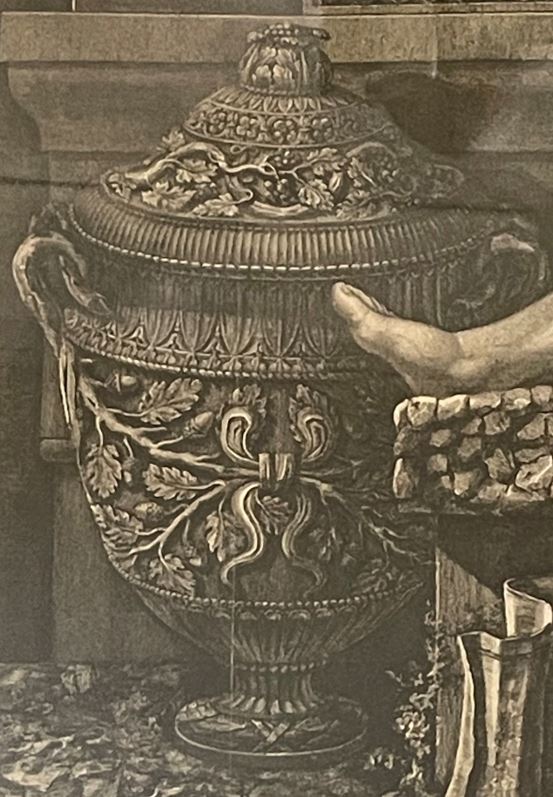

The vase in this etching is known as the Medici vase and at the time of publication was in the Galleria delle Statue in the Villa Medici. It is now in the Uffizi Gallery in Florence. It is believed to have been made about AD 50 to 100 and shows in carved relief the sacrifice of Iphigenia, daughter of Agamemnon, King of Mycenae. Iphigenia is flanked by the figures of Ulysses and Agamemnon.

Alongside Piranesi’s other publications, the series of prints published in Vasi…had a major influence on the development of the neo-classical style and served as source material for many architects and designers. In particular Piranesi was well known among wealthy English visitors to Rome who were frequent visitors to his workshop and who used the Grand Tour to add to their collections of antiquities.

His prints not only showcased his technical mastery but also revolutionized the understanding and appreciation of architectural and decorative motifs from ancient civilizations.

Piranesi's prints primarily focused on architectural subjects, particularly the ruins of ancient Rome. His meticulous attention to detail and his ability to capture the grandeur and magnificence of these architectural remnants made his prints highly sought after by collectors, architects, and designers of the time.

These prints were not only accurate representations but also imaginative interpretations of ancient Roman structures. Piranesi employed dramatic lighting, exaggerated perspectives, and intricate detailing to create a sense of awe and monumentality in his prints.

The "Views of Rome" series, with its exploration of ancient architectural forms, had a significant impact on the decorative arts. It influenced the Neoclassical movement, which emerged in the late 18th century and sought to revive the aesthetics of ancient Greece and Rome. The prints provided a rich source of inspiration for architects, interior designers, and craftsmen who sought to incorporate classical motifs into their creations. The grandeur and richness of Piranesi's prints served as a reference for the scale, proportion, and ornamentation of decorative elements.

An imaginary view showing examples of ancient Roman decorative styles.

The intricate details and decorative motifs found in his prints were often adapted and incorporated into the design of furniture, textiles, ceramics, and other decorative objects. The elaborate ornamentation, such as foliate motifs, mythical creatures, and architectural elements, became popular decorative motifs in the decorative arts of the time.

Furthermore, Piranesi's prints played a crucial role in shaping the perception and understanding of ancient architecture. His interpretations of ancient Roman ruins presented a romanticized and idealized vision of the past. This romantic notion of antiquity, influenced by Piranesi's prints, permeated the decorative arts, as well as literature and visual arts of the time.

Vasi, Candelabri, Cippi, Sarcofagi, Tripodi, Lucerne, Ed Ornamenti Antichi Disegn Ed Inc Dal Cav. Gio. Batta. Piranesi, pubblicati l’anno MDCCLXXIIX.

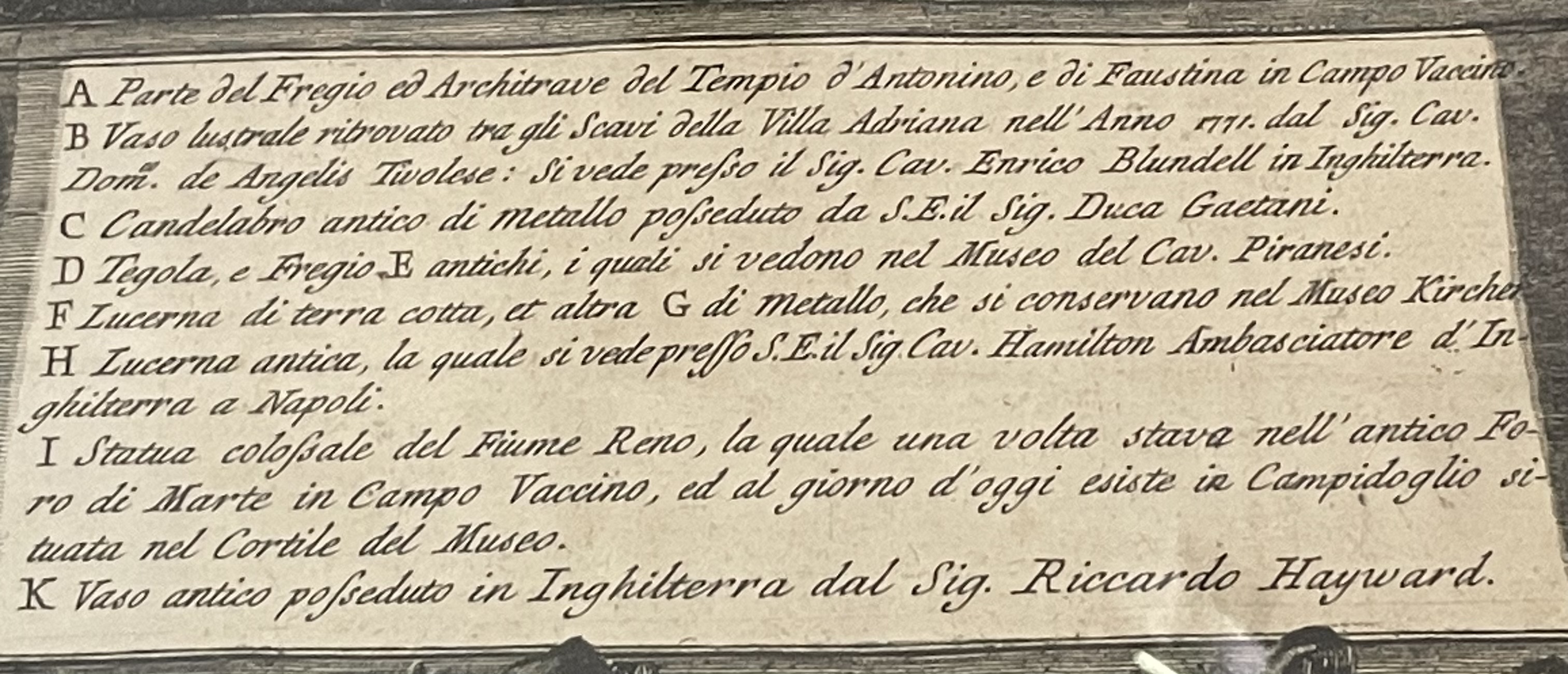

One of the plates that Piranesi produced including text with information on the circumstances of discovery of each object and their contemporary location:

A. Part of the Frieze and Architrave of the Temple of Antonino, and of Faustina in Campo Vaccine

B. Lustral vase found in the excavations of Villa Adriana in the year m. by Mr. Cav. Dom. de Angelis Tivolese: It can be seen with Mr. Cav. Henry Blundell in England.

C. Ancient metal candlestick owned by His Excellency Duke Gaetani.

D. Tile, and Frieze E. Ancient, which can be seen in the Museo del Cav. Piranesi.

F. Lantern of terracotta, et al & metal, which are conserved in the Kircher Museum

H. Ancient Lantern, which can be seen by His Excellency Mr. Cav. Hamilton Ambassador of England in Naples.

I. Colossal statue of the river Reno, which once stood in the ancient Foro di Marte in Campo Vaccino, and nowadays it exists in Campidoglio, located in the courtyard of the museum.

K. Ancient vase owned in England by Mr. Riccardo Hayward.

This last group of plates had a huge influence on the decorative arts and in particular silver items produced in the late 18th and early 19th century. Many of the treasures produced bore a direct link to the items found in the prints. Here are a few examples, currently in the Koopman Rare Art Collection that illustrate the influence of Piranesi:

A Pair of 19th Century Regency Sugar Urns or Vases

Koopman Rare Art Collection

by Paul Storr

London, 1816

Weight: 51 oz. (1617gr.)

Height: 7 5/8 in. (19.4cm.)

Sugar Urns with classical urn form cast with bands of scrolling foliage, serpent hoop handles, leaf and dart base rims, bud finials, the rims engraved with 1817 presentation inscription, fully marked and with stamped number 853.

The inscription reads, "The Gift of Maria F. Heathcote to Thomas Freeman Heathcote 1817."

The source of the design for these sugar vases is a Roman urn in the celebrated antique sculpture collection of the 1st Marquess of Lansdowne, identified by David Udy in Piranesi's Vasi, the English Silversmith and his Patrons, Burlington Magazine, December 1978, p. 837, fig. 55-57. Unlike the Warwick Vase, which had been popularized by Piranesi's engravings of the Eighteenth Century, the Lansdowne urn apparently was reproduced directly in silver before John Duit engraved it around 1813. The design in silver is attributed to the sculptor John Flaxman, who used a variation of the urn in his tomb monument for Sir Thomas Burrell in 1796. Flaxman became Rundell's most important designer around the time the firm became Royal Goldsmiths in 1804.

Many examples are known, including a set of eight by Benjamin and James Smith, 1808, in the Royal Collection. A set of four by Paul Storr, 1816-17, with the crest of the Dukes of Norfolk, is in the Jerome and Rita Gans collection at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts (cat. no. 45).

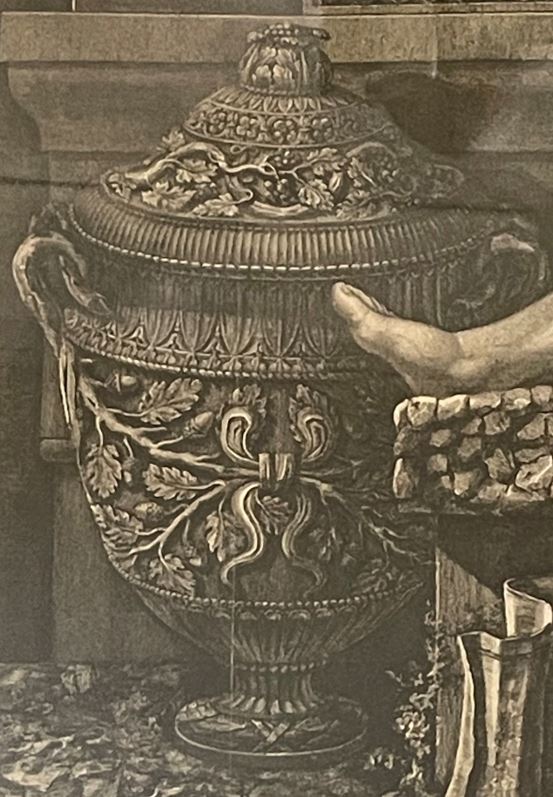

Giovanni Battista Piranesi found at the Pantanello, Hadrian's Villa, Tivoli, in 1770 (The "Warwick Vase"), 1773-78

A George IV Silver-Gilt Warwick Vase

Koopman Rare Art Collection

London in 1821

Made by Paul Storr

Weight: 172 oz 5 dwt, 5361.5 g

Length over handles: 14½in., 36.8 cm

The Warwick vase

The Warwick Vase, an ancient Roman marble vase with Bacchic ornament that was discovered at Hadrian's Villa, Tivoli about 1771 by Gavin Hamilton, a Scottish painter-antiquarian and art dealer in Rome, and is now in the Burrell Collection near Glasgow in Scotland.

The vase was found in the silt of a marshy pond at the low point of the villa's extensive grounds, where Hamilton had obtained excavation rights and proceeded to drain the area. Hamilton sold the fragments to Sir William Hamilton, British envoy at the court of Naples from whose well-known collection it passed to his nephew George Greville, 2nd Earl of Warwick, where it caused a sensation.

A Pair of Geo IV Warwick Vase Caviar / Wine Coolers

Koopman Rare Art Collection

London, 1821

Maker’s mark of Paul Storr

Weight: 6,740 g

Height: 19.5 cm, 7.6 in

Width: 22 cm, 8.6 in

The Victoria and Albert Museum collection formerly with Koopman Rare Art

The Hamilton-Beckford Candlesticks

The Hamilton-Beckford CandlesticksA highly important pair of George III silver-gilt candlesticks after a roman 1st century bronze lampstand

Mark of Charles Aldridge, London, 1787

Each on three matted claw feet with fluted knees above supporting a broad detachable circular plate chased with palm foliage border and inner bands of arcading and alternate panels of differing formal foliage, the detachable fluted stem rising from fluted plinth and of shaped square section, the detachable baluster upper part of the stem and vase-shaped socket chased with further bands of fluting and varying foliage, the detachable circular wax-pan with fluted and ovolo bands, fully marked on lower plates, part-marked on reverse of sockets and on wax-pans

21 3/8 in. (54.3 cm.) high

85 oz. 10 dwt. (2,020 gr.) (2)

Provenance:

William Beckford, MAGNIFICENT EFFECTS AT FONTHILL ABBEY, WILTS; Christie's, 8-17 October 1822 (sale cancelled), either Lot 44 or 45:

44. A PAIR of CANDELABRA of SILVER CHASED and GILT, supported on feet shaped as Lizards

These superb pieces of Plate are truly in classical taste, being executed from the design of a candelabrum found at HERCULANEUM

45. A PAIR of DITTO

William Beckford, The Unique and Splendid effects of Fonthill Abbey; the extensive assemblage of costly and interesting property, which adorns this magnificent structure; Phillips, 23 September-22 October, 1823, either lot 1544 or 1545, with almost identical descriptions and footnote to those in the Christie's catalogue above, located in The Grand (Damask) Drawing Room, No. 24 and sold as one lot for £105.15 to Broadway.

One pair of the two above:

Richard Plantagenet Temple-Nugent-Brydges-Chandos-Grenville, 2nd Duke of Buckingham (1823-1889).

The contents of STOWE HOUSE, near Buckingham, Christie's 15 August-30 September, 1848, lot 783, under the heading GILT

783. A pair of very elegant candelabra, on tripod feet-after those from Herculaneum-from Fonthill 86 ozs. (£98.18s to ?Nathan Jnr.).

Literatue:

M. Snodin and M. Baker, 'William Beckford's Silver II,' The Burlington Magazine, December, 1980, p. 827, under the heading 'English Silver probably or certainly contemporary', no. E3 where the buyer at the Stowe sale is given as S. Peto, M.P.

Related literature:

The Roman original (British Museum Reg.1772.3-4.59) is discussed in:

P. F. d'Hancarville. MS Catalogue des antiquités recueillies, depuis l'an 1764 jusque vers le milieu de l'année 1776 par Mr. Le Chevalier Guillaume Hamilton, acquises par Acte du Parlement en 1772 et maintenant déposéés dans le Muséum Britannique, London 1778, vol. 1, p. 301A.

E. Hawkins, MS Catalogue of the Bronzes in the British Museum, vol. III, p. 166.

D. Bailey, et al, A Catalogue of the Lamps in the British Museum, London, 1996, vol. IV, pp. 91-2, no. Q. 3867, pls. 102 and 103 (schematic drawing).

D'Hancerville (op. cit.) says, in translation, of the original Roman lampstand, which he calls a candelabrum 'close to six foot high', that 'there does not exist at Herculanum [sic] any other as beautiful, nor one which is more perfectly conserved.' This is included in a list in two volumes of the first collection of antiquities formed by Sir William Hamilton, envoy to the Court of Naples from 1764-1800, which was sold to the newly established British Museum following an act of Parliament in 1772 to raise the £8,400 necessary for the purchase.

SPECIAL NOTICE

Sir William Hamilton (1730-1803)

Sir William was a passionate collector of antiquities but also one who 'took seriously his part in the traditional role of the enlightened British aristocracy as patrons of the arts and as promoters of good taste in contemporary manufacture. The sale of the first collection to the British Museum in 1772 was more than a mere financial transaction, for it formed part of a life long mission to raise British, indeed European consciousness in what are now called the decorative arts.' (I. Jenkins " 'Contemporary Minds' Sir William Hamilton's affair with Antiquity", in the exhibition catalogue, Vases and Volcanoes, London, 1996, p. 59). Apart from his collections of Greek and Roman vases, cameos and bronzes Sir William also owned, at least for a short time, the celebrated Portland and Warwick Vases.

He applied for his official position in Naples largely in the hope that it would be beneficial for his wife, Catherine's health. While there they naturally played host to a stream of wealthy and artistic visitors from across Europe which included Mozart and Goethe as well as his second cousin, William Beckford in 1780 and, shortly before Lady Hamilton's death, again in the summer of 1782. A year after Hamilton's return to England in 1799 he, his second wife, Emma and Admiral Lord Nelson spent Christmas as Beckford's guests at Fonthill. Only the St. Michael Gallery had been completed but the effect must have been breathtaking, 'illuminated', as it was, 'with a grand display of wax lights, on candlesticks and candelabras of massive silver-gilt exhibiting a scene at once strikingly splendid and awfully magnificent' (The Gentleman's Magazine, LXXI, p.298).

Charles Aldridge, the Silversmith (w. 1766-1793)

Normally one would expect the silversmith to use a print source for the design of such unusual objects and several illustrations of Roman lampstands from the second half of the 18th century are known, most notably those that appear in the last of eight volumes of Le Antichitá di Ercolano Esposte, Naples, 1757-92. Indeed, a generation after these candlesticks were made, a pair of ormolu torchéres, now in the Royal collection, were supplied to the Prince Regent. They are described in Rundell's bill of 1811 as being 'after those found in the ruins of Herculaneum' and are based on two images illustrated in this important work (pl. LXXI, the base on p. 77, the socket on p. 92; the Regency torchéres are illustrated in the exhibition catalogue, Carlton House, The Past Glories of George IV's Palace, London, 1991-2 p. 91, no. 43). However, the present candlesticks appear to be based directly on the original Roman bronze lampstand which was available of course as a prototype for study at the British Museum in London.

The silversmith Charles Aldridge was apprenticed to Edward Aldridge, presumed to be his uncle, in 1758. He entered his first mark in partnership with Henry Green in 1775 and a second mark alone in 1786. He has followed faithfully the ornament of the Roman original in producing these candlesticks, which are almost exactly a third of the size of the prototype. Allowing for the change of use to a candlestick, the construction with detachable tripod foot, circular plate, distinctive fluted and fourfold stem of cross-shape section and detachable crater-shaped top also follows that of the Hamilton lampstand. The main variations are in the feet that have metamorphosed from lions' paws to lizards' claws and their profile which has been altered, presumably because of the lighter load they have to carry in the 18th century version. In addition an extra baluster has been removed beneath the socket and the flat top of the original has been replaced by a detachable nozzle to reflect the change of function.

Charles Aldridge is not particularly noted for the originality of his designs. Much more typical of his work is the teapot he made with Henry Green for William Beckford in 1782 now at Brodick Castle (T. Schroder, et al, Beckford and Hamilton Silver from Brodick Castle, London, 1980, no. B11). It is also of interest that the maker James Aldridge who produced so many of the most imaginative mounted pieces for Beckford from circa 1815-1823 was apprenticed, and surely related, to Charles Aldridge.

William Beckford (1760-1844)

William Beckford and the silver he ordered has been studied in great detail by Michael Snodin and Malcolm Baker (op. cit.) and the former in 'William Beckford and Metalwork' in the exhibition catalogue William Beckford 1760-1844, An Eye for the Magnificent, New York, 2001, pp. 203-215. His early purchases tend to be standard if sometimes exceptionally well-designed examples of domestic silver which he seems frequently to have taken with him on his extensive travels. While Beckford was mainly in Lisbon in 1787 it is known that a considerable amount of furnishing was underway at Fonthill House, later known as Fonthill Splendens, that summer being mainly designed by the architect John Soane (William Beckford, 1760-1844, op. cit. p.60).

It seems reasonable to assume that Beckford, given the extraordinary originality of his later silver purchases, specially commissioned these remarkable candlesticks rather than acquiring them second hand. Even without the Beckford connection these candlesticks are of exceptional interest. They are based directly on an identifiable object sold with the intention of providing prototypes to the artists and artisans of his day, by Sir William Hamilton in 1772 to the British Museum where it remains.

A Pair of Large Candelabra for Five Lights

Silver-gilt

London, 1817-18

Maker’s mark of Paul Storr

Height: 32.5 in, 82.5 cm

Weight: 1,167 oz 15 dwt, 36,317 g

The foliated and scrolled branches spring from an acanthus vase, the candle-sockets being vase-shaped. The stem is a concave fluted drum, with acanthus edges. Two large griffins, and two tripod vases with serpents, stand on a plain base, which rests on four feet enriched with shells and vines.

The Royal arms of George III are engraved on the base, the badge of George IV as prince of Wales on the stem. Under the base is a plate engraved with the same royal arms reversed to reflect in the plateau.

From the Royal Collection of Silver & Gold at Windsor Castle.

London, 1817-18

Maker’s mark of Paul Storr

Height: 32.5 in, 82.5 cm

Weight: 1,167 oz 15 dwt, 36,317 g

The foliated and scrolled branches spring from an acanthus vase, the candle-sockets being vase-shaped. The stem is a concave fluted drum, with acanthus edges. Two large griffins, and two tripod vases with serpents, stand on a plain base, which rests on four feet enriched with shells and vines.

The Royal arms of George III are engraved on the base, the badge of George IV as prince of Wales on the stem. Under the base is a plate engraved with the same royal arms reversed to reflect in the plateau.

From the Royal Collection of Silver & Gold at Windsor Castle.