BACK TO LIST

BACK TO LIST

The Lustre of Gold

Man has long been fascinated with the glitter of gold, but its high cost and great softness rendered it impractical for many purposes. Demand for this precious metal drove silversmiths down the ages to devise methods of applying a gold finish to silver. Since ancient times gilding has enhanced silver objects, and items that have undergone that process are referred to as silver gilt, or vermeil in French.

There are various methods of gilding, some more dangerous than others. That used in pre-Columbian South America by the Incas was depletion gilding, producing a layer of nearly pure gold on an object of gold alloy by the removal of the other metals from its surface. Another method is overlaying, or the folding of gold leaf, as mentioned in Homer's Odyssey. A third is fire gilding with mercury which involves applying an amalgam of gold and mercury to a silver surface. Heat volatizes the mercury and bonds a strong layer of gold to the silver. Although dangerous for the worker, this method, dating back to the sixth century BC, was used until comparatively recently. It has now been superseded almost entirely by electroplating in which electrolysis is used to coat the surface with gold. This process was finally patented in 1840 by John Wright under the watchful eye of Frederick Elkington the great Victorian retailers of Birmingham.

The process of gilding, however, was costly. While in 1664 Samuel Pepys complained that the cost to "fashion", or the making of a piece, had risen to the same level as the raw material itself (both were 5 shillings an ounce), gilding the finished article could cost an additional 3 shillings an ounce.

I was fortunate to handle a fine pair of silver-gilt baskets made in London, 1766-7, by Parker and Wakelin in 2007. Documentation in the form of ledgers from their time of making shows that gilding added approximately 25 per cent to the total cost; this was considerably more than commissioning an object in silver yet still less than one produced in gold. By the Middle Ages, European gold was worth ten to twelve times more than silver, but by the eighteenth a nineteenth centuries the price ratio had risen to fifteen to one. Even so, achieving the golden look through gilding became ever more popular.

“There was never perhaps an occasion where more plate was brought together in one place “recalled George Fox, Rundells shopman writing in the 1840s on the banquet given by the Corporation of London for the Prince Regent, the Emperor of Russia and the King of Prussia on 18 June 1814. Painting by Luke Clennal.

Madame Mère’s inkstand by Jean-Baptiste Claude Odiot, Paris 1809-1819

The Burghley Nef made in Paris in 1527–28.

In Renaissance Europe the cabinets of curiosities (Wunderkammern) of noble households held vast collections in which many wonders from the New World, such as shells, mother of pearl and precious or semi-precious stones, were mounted in silver gilt to set off their beauty and flaunt the knowledge of their owners. Being silver gilt greatly reduced the need to clean and polish them, for gold tarnishes far more slowly than silver. This reduced the risk of an object being damaged, and often gilded items have survived in better condition than their silver counterparts.

I am delighted to introduce a beautiful selection of treasures from our collection that highlight the splendour of gilded silver. The collection of silver-gilt objects spans centuries, and each triumph of the decorative arts highlights not only the splendour and richness of gilded silver, but also reflects the socio-economic importance that it has always held.

The Grenville-Temple Tazza made in London, 1701 by Anthony Nelme

This footed salver which bears the coat-of-arms of Grenville accollé with Leofric quartering Temple would have graced the tables at Stowe House in Buckinghamshire at the time it was made. Its creator, the great Anthony Nelme was free of the Goldsmiths' Company in 1690 was elected to the court of assistants in 1703. He was made fourth warden in 1717 and then second warden in 1722. During the period of Huguenot prominence, Nelme was the leading English-born goldsmiths and was a signatory to the petitions to the Goldsmith Company wardens protesting the presence of the "necessitous strangers" in London. Queen Anne and the leading members of the aristocracy were some of Nelme's patrons. Among most of his important surviving works are a pair of forty-inch alter candlesticks of 1694 at Saint George's Chapel, Windsor (Honour 1971, p. 122), and a pair of pilgrim bottles of 1715 at Chatsworth. Here the gilded surface enhances the elegance and simplicity of an object that one finds in in so many old master still life paintings. Interestingly a salver was defined in 1661 dictionary as "a new peece of wrought plate, broad and flat, with a foot underneath, and is used in giving Beer or other liquid to save the Carpitt or Clothes from drops”.

Thomas Lumley-Saunderson was elected without opposition as M.P. for Lincolnshire in 1727 and applied for a peerage as Lord Castleton's heir, but his request was unsuccessful due to King George II's reluctance to grant peerages. He joined the opposition and consistently voted against the government, frequently speaking on matters related to the army and foreign affairs. He was re-elected unopposed for Lincolnshire in 1734 and continued to align with the opposition. In 1737, he was among the Members of the House of Commons who were consulted by the Prince of Wales regarding an application to Parliament for an increase in his allowance. He expressed support and spoke in favour of the increase, which earned him the position of treasurer to the Prince in 1738. In 1740, he succeeded to the earldom of Scarbrough and with these two posts would have needed the most splendid and fashionable plate of the day.

Thomas Lumley-Saunderson, 3rd Earl of Scarbrough’s sauce boats, circa 1750 attributed to Nicholas Sprimont

These sculptural sauceboats epitomise the high Rococo style popular in mid-18th century London and the close ties between the modelling of silver and porcelain at the time, with the interconnected business relationships between a small group of leading silversmiths working around Compton Street in Soho. A study of Sprimont’s oeuvre in silver shows a close relationship with fellow Huguenot silversmith Paul Crespin (1694-1770), whose workshop was also located in Compton Street. There is compelling evidence to attribute sauceboats of this form to either silversmith.

A pair of sauceboats, almost identical to the present lot, with the mark of Crespin, hallmarked for 1746, are in the collection of The Sterling and Francine Clarke Art Institute, Williamstown, Massachusetts. Beth Carver Wees, op. cit., p. 167 also notes that similar sauceboats were also produced by another Huguenot silversmith, Pezé Pilleau, whose son Isaac married a Jane Crespin, possibly Paul's daughter. A further set of four similar sauceboats marked by Crespin were sold at Christie’s, London on 26 March 1975, lot 73.

It is thought that either Sprimont worked as a modeller for Crespin, prior to registering his own mark and setting up as an independent silversmith, or that there was an exchange of casts and models between the two, and indeed a wider circle of silversmiths, as shown by a pair of candlesticks by Sprimont of 1745, also in the collection of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, which are identical to a pair by Paul de Lamerie, of 1747, sold Christie's, New York, 14 April 2005, lot 234. The influence of the French master silversmith François-Thomas Germain is evident from a sauceboat, once in the Portuguese Royal Collection, illustrated by Hartop, op. cit., p. 218, from G. Bapst, L'Orfèvrerie Français à la Cour de Portugal au XVIIIe siècle, Paris, 1892, pl. XIV, fig. 50.

As Ellenor Alcorn points out, op. cit., p. 162, the links with Crespin are strong. Similar cast coral and shell ornament is found on a small teapot by Crespin of 1740, offered for sale at Christie's London, 3 March 1993, lot 247, now in the Hartman Collection, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Alcorn also notes similar decoration on a Crespin coffee pot of the same year advertised by Spink in the Connoisseur in 1946. Crespin and Sprimont collaborated on the Prince of Wales's Neptune centrepiece. Although the piece is struck with Crespin's mark, the similarity with Sprimont's later work, including the other pieces by him for the Marine Service, has led scholars to include this piece in his list of works.

Sprimont was involved with the Chelsea Porcelain Manufactory as early as 1745. He translated a number of his designs for silver into works in porcelain, such as the stand for the Rockingham Sauceboats, which are referred to as 'silver shape' in Ford's auction catalogue for the Chelsea Porcelain Manufactory held in 1755 and discussed by Dr. Bellamy Gardner in his article 'Silvershape in Chelsea Porcelain', published in The Antique Collector, August, 1937, p. 213. Further influence of silver designs on the porcelain of the time is shown by a Derby sauceboat in the Victoria and Albert Museum collection, illustrated by Hartop, op. cit., p. 218. The Rockingham set of four sauceboats and stands suggests Sprimont as the likely maker for the present lot; the sauceboats are similarly unmarked, however the stands are fully marked for Sprimont, London, 1746. A pair was sold in The Exceptional Sale, Christie's London, 22 July 2020, lot 42; a further pair is in the collection of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

The Earl of Grosvenor’s Triton Salt Cellars London, 1810 by Paul Storr.

The Shield of Achilles

four times in silver for the king, the Duke of York, the Duke of Northumberland and Lord Lonsdale. Gilded the article costs £2000, ungilded £1900” (exhibition catalogue, see Literature, pp. 30-31). This gives the impression that only four shields were made although Schorn must have been looking at the fifth example which is the one sold to the Duke of Cumberland. In 1911 E. Alfred Jones stated that an example had been made for the King of Hanover: “A shield of exactly the same design and of equal size but two years later in date is in the possession of the duke of Cumberland”. Jones must have seen the shield as he makes it clear in the acknowledgements that he was given access to the Hanoverian royal collection. Christopher Hartop realised that there were five shields but did not know of the whereabouts of the Cumberland shield in 2005.

The shields were not made to a commission but were a speculative exercise and it would seem that this shield remained in Rundell’s shop on display as a magnificent testament to the supreme skills of their craftsmen and designers. The company, who were excellent self-publicists, would have used the shield as an advertisement to maximum advantage. It was probably sold to the Duke of Cumberland after his accession to the throne of Hanover in 1837 and probably in 1838 as attested by the inscription on the reverse of the shield. The arms must have been engraved after 1839 as they incorporate the Order of St. George of Hanover which was instituted by Ernst Augustus in April 1839. The new Hanoverian monarch acquired massive quantities of plate in 1838 amounting to over 180 kilos and including six thirteen light candelabra and two centrepieces. This great display of plate would have played an important role in the establishment of the new king and the image of splendour that he wished to create for himself. Unlike his brother George IV, he did not acquire plate for the specific occasion of his coronation.

The shield appears in a photograph of the Hanoverian royal plate on display in Vienna in 1868. There is no record of the sale of the shield but much of the Hanoverian royal plate was disposed of in 1923 after the death of Crown Prince Ernst Augustus II by the dealers and auctioneers Samuel and Max Glückselig of Vienna and Crichton Brothers of London and it is probable that it was sold at this time.

Flaxman in his design adhered closely to the description given by Homer. The design of the shield revolves around the central figure of the Apollo is his chariot of the sun. The frieze, arranged in a succession of groups, depicts the marriage procession and banquet, the quarrel and judicial appeal, the siege and ambuscade and military engagement, the harvest, the vintage, the shepherds defending their herds of cattle from the attack of lions and a Cretan dance. The great stream of the ocean is represented by the surrounding border. Flaxman’s drawings for the shield are in the collections of the British Museum and what is believed to be the original cast for the shield is in the Sir John Soane Museum, London. Allan Cunningham (The Lives of the most eminent British Painters, Sculptors, and Architects, 1833, vol. III) suggested that Flaxman used a translation of the Iliad when working on his design although this was contradicted by Maria Denman, Flaxman’s sister-in-law, who insisted that he had worked from the original Greek text.

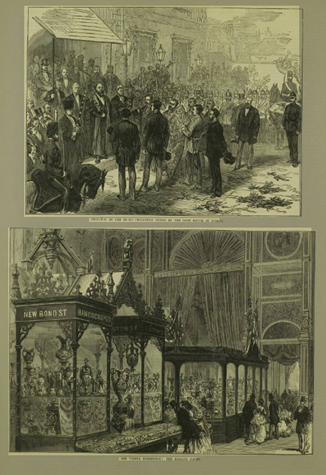

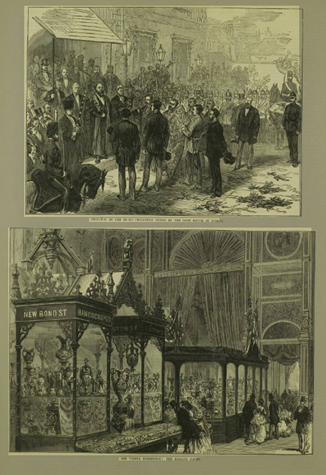

Hancocks at the Viena Exhibition 1873

An Exceptional Victorian Ewer 1873 by Charles Frederick Hancocks

There are various methods of gilding, some more dangerous than others. That used in pre-Columbian South America by the Incas was depletion gilding, producing a layer of nearly pure gold on an object of gold alloy by the removal of the other metals from its surface. Another method is overlaying, or the folding of gold leaf, as mentioned in Homer's Odyssey. A third is fire gilding with mercury which involves applying an amalgam of gold and mercury to a silver surface. Heat volatizes the mercury and bonds a strong layer of gold to the silver. Although dangerous for the worker, this method, dating back to the sixth century BC, was used until comparatively recently. It has now been superseded almost entirely by electroplating in which electrolysis is used to coat the surface with gold. This process was finally patented in 1840 by John Wright under the watchful eye of Frederick Elkington the great Victorian retailers of Birmingham.

The process of gilding, however, was costly. While in 1664 Samuel Pepys complained that the cost to "fashion", or the making of a piece, had risen to the same level as the raw material itself (both were 5 shillings an ounce), gilding the finished article could cost an additional 3 shillings an ounce.

I was fortunate to handle a fine pair of silver-gilt baskets made in London, 1766-7, by Parker and Wakelin in 2007. Documentation in the form of ledgers from their time of making shows that gilding added approximately 25 per cent to the total cost; this was considerably more than commissioning an object in silver yet still less than one produced in gold. By the Middle Ages, European gold was worth ten to twelve times more than silver, but by the eighteenth a nineteenth centuries the price ratio had risen to fifteen to one. Even so, achieving the golden look through gilding became ever more popular.

“There was never perhaps an occasion where more plate was brought together in one place “recalled George Fox, Rundells shopman writing in the 1840s on the banquet given by the Corporation of London for the Prince Regent, the Emperor of Russia and the King of Prussia on 18 June 1814. Painting by Luke Clennal.

Silver-gilt objects were often used as status symbols, as exemplified by a painting of the Guildhall Banquet held in 1814 for the Prince Regent, the Tsar of Russia, and the King of Prussia. One dinner service is in silver gilt and the other quite intentionally in silver: guests seated with the silver-gilt service are "superior" to those with the silver service. They are also seated in an elevated position over their guests.

However, in French silver, many of the important services that have survived to date are entirely in silver gilt. Take for example the early nineteenth-century services for General Count François-Xavier Branicki, or for Count Nikolai Demidoff, or indeed the Borghese service or that made for Madame Mère, the mother of Napoleon. These grand dinner services were nearly all produced by Jean-Baptiste-Claude Odiot and Martin-Guillaume Biennais, both of whom executed imperial commissions.

However, in French silver, many of the important services that have survived to date are entirely in silver gilt. Take for example the early nineteenth-century services for General Count François-Xavier Branicki, or for Count Nikolai Demidoff, or indeed the Borghese service or that made for Madame Mère, the mother of Napoleon. These grand dinner services were nearly all produced by Jean-Baptiste-Claude Odiot and Martin-Guillaume Biennais, both of whom executed imperial commissions.

Madame Mère’s inkstand by Jean-Baptiste Claude Odiot, Paris 1809-1819

In this period popularity of silver-gilt items soared on both sides of the Channel, with the English royal goldsmiths Rundell, Bridge & Rundell and master silversmiths Paul Storr and Benjamin Smith leading the way. Their most important patrons were King George III, the Prince Regent (later George IV) and various children of the royal family.

Gold, unlike silver, is neither affected by the corrosiveness of salt nor by discoloration by sulphur, nor indeed by the acidity of many of the desserts that were popular at this time. Both silver and silver-gilt dessert services were thus used not merely to denote status but also for a practical reason: after the main course was served on plain silver, the main service was replaced or complemented by the silver-gilt dessert service, sometimes with diners adjourning to a separate room for dessert.

Aside from being less expensive than gold, silver-gilt items are lighter in weight and much more durable. Therefore, many delicate objects were made in silver gilt. The nef (cf. the Burghley nef) is a dinner-table ornament or utilitarian vessel in the form of a ship. It dates from the thirteenth to the sixteenth century and was used as a drinking vessel or salt cellar. Indeed, the salt cellar is where silver gilt truly excelled. From medieval times, people recognized the importance of salt as a preservative.

Elaborate and grand vessels were made to sit on the table before the master of the house. The expression "right hand man" used today derives from one's position at the table in relation to the salt cellar.

Gold, unlike silver, is neither affected by the corrosiveness of salt nor by discoloration by sulphur, nor indeed by the acidity of many of the desserts that were popular at this time. Both silver and silver-gilt dessert services were thus used not merely to denote status but also for a practical reason: after the main course was served on plain silver, the main service was replaced or complemented by the silver-gilt dessert service, sometimes with diners adjourning to a separate room for dessert.

Aside from being less expensive than gold, silver-gilt items are lighter in weight and much more durable. Therefore, many delicate objects were made in silver gilt. The nef (cf. the Burghley nef) is a dinner-table ornament or utilitarian vessel in the form of a ship. It dates from the thirteenth to the sixteenth century and was used as a drinking vessel or salt cellar. Indeed, the salt cellar is where silver gilt truly excelled. From medieval times, people recognized the importance of salt as a preservative.

Elaborate and grand vessels were made to sit on the table before the master of the house. The expression "right hand man" used today derives from one's position at the table in relation to the salt cellar.

The Burghley Nef made in Paris in 1527–28.

In Renaissance Europe the cabinets of curiosities (Wunderkammern) of noble households held vast collections in which many wonders from the New World, such as shells, mother of pearl and precious or semi-precious stones, were mounted in silver gilt to set off their beauty and flaunt the knowledge of their owners. Being silver gilt greatly reduced the need to clean and polish them, for gold tarnishes far more slowly than silver. This reduced the risk of an object being damaged, and often gilded items have survived in better condition than their silver counterparts.

I am delighted to introduce a beautiful selection of treasures from our collection that highlight the splendour of gilded silver. The collection of silver-gilt objects spans centuries, and each triumph of the decorative arts highlights not only the splendour and richness of gilded silver, but also reflects the socio-economic importance that it has always held.

The Grenville-Temple Tazza made in London, 1701 by Anthony Nelme

This footed salver which bears the coat-of-arms of Grenville accollé with Leofric quartering Temple would have graced the tables at Stowe House in Buckinghamshire at the time it was made. Its creator, the great Anthony Nelme was free of the Goldsmiths' Company in 1690 was elected to the court of assistants in 1703. He was made fourth warden in 1717 and then second warden in 1722. During the period of Huguenot prominence, Nelme was the leading English-born goldsmiths and was a signatory to the petitions to the Goldsmith Company wardens protesting the presence of the "necessitous strangers" in London. Queen Anne and the leading members of the aristocracy were some of Nelme's patrons. Among most of his important surviving works are a pair of forty-inch alter candlesticks of 1694 at Saint George's Chapel, Windsor (Honour 1971, p. 122), and a pair of pilgrim bottles of 1715 at Chatsworth. Here the gilded surface enhances the elegance and simplicity of an object that one finds in in so many old master still life paintings. Interestingly a salver was defined in 1661 dictionary as "a new peece of wrought plate, broad and flat, with a foot underneath, and is used in giving Beer or other liquid to save the Carpitt or Clothes from drops”.

Thomas Lumley-Saunderson was elected without opposition as M.P. for Lincolnshire in 1727 and applied for a peerage as Lord Castleton's heir, but his request was unsuccessful due to King George II's reluctance to grant peerages. He joined the opposition and consistently voted against the government, frequently speaking on matters related to the army and foreign affairs. He was re-elected unopposed for Lincolnshire in 1734 and continued to align with the opposition. In 1737, he was among the Members of the House of Commons who were consulted by the Prince of Wales regarding an application to Parliament for an increase in his allowance. He expressed support and spoke in favour of the increase, which earned him the position of treasurer to the Prince in 1738. In 1740, he succeeded to the earldom of Scarbrough and with these two posts would have needed the most splendid and fashionable plate of the day.

Thomas Lumley-Saunderson, 3rd Earl of Scarbrough’s sauce boats, circa 1750 attributed to Nicholas Sprimont

These sculptural sauceboats epitomise the high Rococo style popular in mid-18th century London and the close ties between the modelling of silver and porcelain at the time, with the interconnected business relationships between a small group of leading silversmiths working around Compton Street in Soho. A study of Sprimont’s oeuvre in silver shows a close relationship with fellow Huguenot silversmith Paul Crespin (1694-1770), whose workshop was also located in Compton Street. There is compelling evidence to attribute sauceboats of this form to either silversmith.

A pair of sauceboats, almost identical to the present lot, with the mark of Crespin, hallmarked for 1746, are in the collection of The Sterling and Francine Clarke Art Institute, Williamstown, Massachusetts. Beth Carver Wees, op. cit., p. 167 also notes that similar sauceboats were also produced by another Huguenot silversmith, Pezé Pilleau, whose son Isaac married a Jane Crespin, possibly Paul's daughter. A further set of four similar sauceboats marked by Crespin were sold at Christie’s, London on 26 March 1975, lot 73.

It is thought that either Sprimont worked as a modeller for Crespin, prior to registering his own mark and setting up as an independent silversmith, or that there was an exchange of casts and models between the two, and indeed a wider circle of silversmiths, as shown by a pair of candlesticks by Sprimont of 1745, also in the collection of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, which are identical to a pair by Paul de Lamerie, of 1747, sold Christie's, New York, 14 April 2005, lot 234. The influence of the French master silversmith François-Thomas Germain is evident from a sauceboat, once in the Portuguese Royal Collection, illustrated by Hartop, op. cit., p. 218, from G. Bapst, L'Orfèvrerie Français à la Cour de Portugal au XVIIIe siècle, Paris, 1892, pl. XIV, fig. 50.

As Ellenor Alcorn points out, op. cit., p. 162, the links with Crespin are strong. Similar cast coral and shell ornament is found on a small teapot by Crespin of 1740, offered for sale at Christie's London, 3 March 1993, lot 247, now in the Hartman Collection, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Alcorn also notes similar decoration on a Crespin coffee pot of the same year advertised by Spink in the Connoisseur in 1946. Crespin and Sprimont collaborated on the Prince of Wales's Neptune centrepiece. Although the piece is struck with Crespin's mark, the similarity with Sprimont's later work, including the other pieces by him for the Marine Service, has led scholars to include this piece in his list of works.

Sprimont was involved with the Chelsea Porcelain Manufactory as early as 1745. He translated a number of his designs for silver into works in porcelain, such as the stand for the Rockingham Sauceboats, which are referred to as 'silver shape' in Ford's auction catalogue for the Chelsea Porcelain Manufactory held in 1755 and discussed by Dr. Bellamy Gardner in his article 'Silvershape in Chelsea Porcelain', published in The Antique Collector, August, 1937, p. 213. Further influence of silver designs on the porcelain of the time is shown by a Derby sauceboat in the Victoria and Albert Museum collection, illustrated by Hartop, op. cit., p. 218. The Rockingham set of four sauceboats and stands suggests Sprimont as the likely maker for the present lot; the sauceboats are similarly unmarked, however the stands are fully marked for Sprimont, London, 1746. A pair was sold in The Exceptional Sale, Christie's London, 22 July 2020, lot 42; a further pair is in the collection of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

The Earl of Grosvenor’s Triton Salt Cellars London, 1810 by Paul Storr.

The celebrated Paul Storr was one of the greatest silversmiths and businessmen to ever work in England and from 1807-1819 operated under the royal retailers Rundell, Bridge & Rundell. The reputation that Storr developed during his time was clearly evident and both the Prince Regent and King George III were great admirers and patrons. Of course, the aristocrats and fast-growing nouveau riche wanted to emulate what the king had at his table.

The Royal Marine service was started in the 18th century and completed by Storr together with Rundell, Bridge and Rundell in the early 19th century. It is still used today by Charles III for state banquets. With England being an island, there was great symbolism in our navy’s importance and the protection of England by the waters surrounding us. Here with this magnificent set of eight triton salt cellars you see the Earl of Grosvenor following the fashions of the royal palace. The royal collection has a set of 24 with oval bases by Paul Storr also dating to 1810, and one is illustrated in Carlton House: The Past Glories of George IV's Palace, 1991, cat. no. 95, p. 133. How of the moment that the Earl of Grosvenor saw fit to commission this set of eight in the very same year.

Perhaps the most iconic gilded object of all recorded pieces in the 19th century is the Shield of Achilles. The spectacular shield is the supreme example of early nineteenth-century English silver and is a triumphant collaboration between the great firm of Rundell and Bridge and the leading designer John Flaxman. “The silver-gilt Shield of Achilles, designed and modelled by one of the greatest English sculptors of the regency, is an outstanding instance of a synthesis of the fine and decorative arts. The designer, John Flaxman was the most illustrious of the Royal Academicians associated with Rundell, Bridge & Rundell ...” (Shirley Bury and Michael Snodin, ‘The Shield of Achilles by John Flaxman R.A., Sotheby’s Art at Auction 1983-4, 1984, pp. 274-83).

Flaxman was “the most famous British sculptor and the brightest star in the Rundell & Bridge firmament” (Christopher Hartop, see Literature, p. 104). From 1805 he had been supplying the firm with drawings of figures and friezes which were then employed on various designs for large pieces of silver such as wine coolers and vases. He actually modelled only one piece for the firm, however, the shield of Achilles. Flaxman’s design is an interpretation of the shield wrought for Achilles by the god Hephaestus at the request of Thetis after Achilles lost his armour which he had lent to Patroclus; it having been seized as the spoils of war by Hector.

“Then first he formed the immense and solid shield

Rich various artifice emblazed the field”

Alexander Pope’s translation of the Iliad

The Renaissance concept of massive display chargers or shields decorated with scenes celebrating great military triumphs had long been out of fashion but was revived by Philip Rundell and John Bridge by 1810, the year in which Flaxman submitted his first designs for this great project. It was to be another seven years before the design was completed to his satisfaction. In 1817 he made the model for the shield himself which was then cast in plaster. The artist Sir Thomas Lawrence was also presented with a plaster version of the shield. He admired and treasured it to the point he decided to mention Flaxman’s masterpiece in his eulogium to the latter describing it as “that Divine Work, unequalled in the combination of beauty, variety and grandeur, which the genius of Michael Angelo could not have surpassed”.

Three or possibly more bronze versions were made and finished by the chaser William Pitts junior and finally in 1819 a silver version was made. It was this shield which was then gilded and sold to George IV in 1821 to form the centrepiece for the buffet of plate at his coronation banquet. Flaxman was initially paid one hundred guineas for ‘4 models and 6 drawings’ and in 1817 he received £200 on account and a further £525 in the following year (John Culme, Important Gold and Silver, sale, Sotheby’s, London, 3rd May 1984, lot 124).

Five silver-gilt shields in all were made. The first, mentioned above, which is in the Royal Collection and a further example which was acquired by Frederick Augustus, Duke of York and is now in the collections of the Huntington Library and Art Gallery, San Marino, California; both of these shields are marked for 1821-22. Two further shields both marked for 1822-23 were sold to Hugh Percy, 3rd Duke of Northumberland in 1822 for £2,100 and to William Lowther, 2nd Earl of Lonsdale in 1823 and are in the collections of His Excellency Mohamed Mahdi Altajir and the National Trust at Anglesey Abbey respectively. The present shield which is marked for 1823-24 was sold to Ernst Augustus, Duke of Cumberland and later King of Hanover and for many years its existence was overlooked.

The reason for this shield being ‘lost’ springs from the belief that only four were actually made and in part this error must arise from the description by the German Ludwig Schorn of his visit in 1826 to the workshops of Rundell’s: “to the silversmiths Rundell & Bridge who kept a splendid shop not far from St. Paul’s on Ludgate Hill. Here I was shown the shield of Achilles cast in silver and chased after a plaster model which Flaxman had executed to the King’s commission ... the shield has been cast

The Royal Marine service was started in the 18th century and completed by Storr together with Rundell, Bridge and Rundell in the early 19th century. It is still used today by Charles III for state banquets. With England being an island, there was great symbolism in our navy’s importance and the protection of England by the waters surrounding us. Here with this magnificent set of eight triton salt cellars you see the Earl of Grosvenor following the fashions of the royal palace. The royal collection has a set of 24 with oval bases by Paul Storr also dating to 1810, and one is illustrated in Carlton House: The Past Glories of George IV's Palace, 1991, cat. no. 95, p. 133. How of the moment that the Earl of Grosvenor saw fit to commission this set of eight in the very same year.

Perhaps the most iconic gilded object of all recorded pieces in the 19th century is the Shield of Achilles. The spectacular shield is the supreme example of early nineteenth-century English silver and is a triumphant collaboration between the great firm of Rundell and Bridge and the leading designer John Flaxman. “The silver-gilt Shield of Achilles, designed and modelled by one of the greatest English sculptors of the regency, is an outstanding instance of a synthesis of the fine and decorative arts. The designer, John Flaxman was the most illustrious of the Royal Academicians associated with Rundell, Bridge & Rundell ...” (Shirley Bury and Michael Snodin, ‘The Shield of Achilles by John Flaxman R.A., Sotheby’s Art at Auction 1983-4, 1984, pp. 274-83).

Flaxman was “the most famous British sculptor and the brightest star in the Rundell & Bridge firmament” (Christopher Hartop, see Literature, p. 104). From 1805 he had been supplying the firm with drawings of figures and friezes which were then employed on various designs for large pieces of silver such as wine coolers and vases. He actually modelled only one piece for the firm, however, the shield of Achilles. Flaxman’s design is an interpretation of the shield wrought for Achilles by the god Hephaestus at the request of Thetis after Achilles lost his armour which he had lent to Patroclus; it having been seized as the spoils of war by Hector.

“Then first he formed the immense and solid shield

Rich various artifice emblazed the field”

Alexander Pope’s translation of the Iliad

The Renaissance concept of massive display chargers or shields decorated with scenes celebrating great military triumphs had long been out of fashion but was revived by Philip Rundell and John Bridge by 1810, the year in which Flaxman submitted his first designs for this great project. It was to be another seven years before the design was completed to his satisfaction. In 1817 he made the model for the shield himself which was then cast in plaster. The artist Sir Thomas Lawrence was also presented with a plaster version of the shield. He admired and treasured it to the point he decided to mention Flaxman’s masterpiece in his eulogium to the latter describing it as “that Divine Work, unequalled in the combination of beauty, variety and grandeur, which the genius of Michael Angelo could not have surpassed”.

Three or possibly more bronze versions were made and finished by the chaser William Pitts junior and finally in 1819 a silver version was made. It was this shield which was then gilded and sold to George IV in 1821 to form the centrepiece for the buffet of plate at his coronation banquet. Flaxman was initially paid one hundred guineas for ‘4 models and 6 drawings’ and in 1817 he received £200 on account and a further £525 in the following year (John Culme, Important Gold and Silver, sale, Sotheby’s, London, 3rd May 1984, lot 124).

Five silver-gilt shields in all were made. The first, mentioned above, which is in the Royal Collection and a further example which was acquired by Frederick Augustus, Duke of York and is now in the collections of the Huntington Library and Art Gallery, San Marino, California; both of these shields are marked for 1821-22. Two further shields both marked for 1822-23 were sold to Hugh Percy, 3rd Duke of Northumberland in 1822 for £2,100 and to William Lowther, 2nd Earl of Lonsdale in 1823 and are in the collections of His Excellency Mohamed Mahdi Altajir and the National Trust at Anglesey Abbey respectively. The present shield which is marked for 1823-24 was sold to Ernst Augustus, Duke of Cumberland and later King of Hanover and for many years its existence was overlooked.

The reason for this shield being ‘lost’ springs from the belief that only four were actually made and in part this error must arise from the description by the German Ludwig Schorn of his visit in 1826 to the workshops of Rundell’s: “to the silversmiths Rundell & Bridge who kept a splendid shop not far from St. Paul’s on Ludgate Hill. Here I was shown the shield of Achilles cast in silver and chased after a plaster model which Flaxman had executed to the King’s commission ... the shield has been cast

The Shield of Achilles

four times in silver for the king, the Duke of York, the Duke of Northumberland and Lord Lonsdale. Gilded the article costs £2000, ungilded £1900” (exhibition catalogue, see Literature, pp. 30-31). This gives the impression that only four shields were made although Schorn must have been looking at the fifth example which is the one sold to the Duke of Cumberland. In 1911 E. Alfred Jones stated that an example had been made for the King of Hanover: “A shield of exactly the same design and of equal size but two years later in date is in the possession of the duke of Cumberland”. Jones must have seen the shield as he makes it clear in the acknowledgements that he was given access to the Hanoverian royal collection. Christopher Hartop realised that there were five shields but did not know of the whereabouts of the Cumberland shield in 2005.

The shields were not made to a commission but were a speculative exercise and it would seem that this shield remained in Rundell’s shop on display as a magnificent testament to the supreme skills of their craftsmen and designers. The company, who were excellent self-publicists, would have used the shield as an advertisement to maximum advantage. It was probably sold to the Duke of Cumberland after his accession to the throne of Hanover in 1837 and probably in 1838 as attested by the inscription on the reverse of the shield. The arms must have been engraved after 1839 as they incorporate the Order of St. George of Hanover which was instituted by Ernst Augustus in April 1839. The new Hanoverian monarch acquired massive quantities of plate in 1838 amounting to over 180 kilos and including six thirteen light candelabra and two centrepieces. This great display of plate would have played an important role in the establishment of the new king and the image of splendour that he wished to create for himself. Unlike his brother George IV, he did not acquire plate for the specific occasion of his coronation.

The shield appears in a photograph of the Hanoverian royal plate on display in Vienna in 1868. There is no record of the sale of the shield but much of the Hanoverian royal plate was disposed of in 1923 after the death of Crown Prince Ernst Augustus II by the dealers and auctioneers Samuel and Max Glückselig of Vienna and Crichton Brothers of London and it is probable that it was sold at this time.

Flaxman in his design adhered closely to the description given by Homer. The design of the shield revolves around the central figure of the Apollo is his chariot of the sun. The frieze, arranged in a succession of groups, depicts the marriage procession and banquet, the quarrel and judicial appeal, the siege and ambuscade and military engagement, the harvest, the vintage, the shepherds defending their herds of cattle from the attack of lions and a Cretan dance. The great stream of the ocean is represented by the surrounding border. Flaxman’s drawings for the shield are in the collections of the British Museum and what is believed to be the original cast for the shield is in the Sir John Soane Museum, London. Allan Cunningham (The Lives of the most eminent British Painters, Sculptors, and Architects, 1833, vol. III) suggested that Flaxman used a translation of the Iliad when working on his design although this was contradicted by Maria Denman, Flaxman’s sister-in-law, who insisted that he had worked from the original Greek text.

Hancocks at the Viena Exhibition 1873

The final piece that we present from our collection of silver-gilt objects is pure sculpture enhanced by the beauty of its gilding. Given how extraordinary this piece is in its nature, a complete unique commission that explores every aspect of craftmanship, design and execution of the goldsmith, it is most likely that piece formed part of Hancock’s display at the 1873 Vienna exhibition.

Likely candidates for the modelling and design who worked closely with the firm Hancock & Co are:

Raffaelle Monti (1818-1881)

The son of the sculptor Gaetano Matteo Monti (1776-1847) of Ravenna and Milan, was something of a prodigy. In his late teens, when he was studying under his father and the sculptor Pompeo Marchesi (1790-1858), a former pupil of Canova, at the Academy of Fine Arts of Brera, Milan, he won several prizes including the Great Gold Medal for his group, 'Alexander Taming Bucephalus.' In 1838, having completed another colossal project, 'Ajax defending the body of Patroculus,' he was invited to go to Vienna to produce various busts for the Imperial family.

Monti's sudden appearance as a widely known celebrity sculptor in the United Kingdom coincided with the display of his work in London at the Great Exhibition of 1851. Before that he had been known in England to only a select group of wealthy patrons, for one of whom, William Cavendish, 6th Duke of Devonshire (1790-1858), he had created in 1847 his celebrated 'Veiled Vestal.

Henry Hugh Armstead RA (1828 – 1905)

Henry Hugh Armstead was born in London in 1828 and received his earliest education in the workshop of his father John, a heraldic chaser. He studied at the Government School of Design at Somerset House from the age of thirteen before attending two privately-run drawing schools.

Armstead was employed by the silversmiths Hunt and Roskell and Hancock &Co while at the same time working in the studio of sculptor Edward Hodges Baily and studying at the Royal Academy Schools. Until around 1863 he concentrated on metalwork, although the lack of recognition he received in this medium led him to turn to sculpture. After his sculptural work was noticed by the Gothic Revival architect George Gilbert Scott, Armstead was employed to create relief panels and other sculptural decorations for buildings including the Palace of Westminster, the Albert Memorial and the Colonial Office (now the Foreign and Commonwealth Office) on Whitehall. His sculpture anticipates the later New Sculpture movement which broadly rejected classicism in favour of realism.

Armstead, who also produced numerous book and magazine illustrations, was elected as a Royal Academician in 1879 (his Diploma Work was a marble relief, The Ever-Reigning Queen). He took an active role in the work of the academy, teaching in the schools for many years and placing the sculpture in many RA exhibitions. He died at his house in London, in 1905.

Both Armstead and Monti together with the architect Owen Jones also produced the ‘Tennyson Vase’ for the Paris 1867 Exhibition for Hancock’s which was purchased at the Exhibition by Napoleon III. The Goodwood Cup of 1866 and Armstead was again involved in the modelling of a Hancock presentation centrepiece commissioned by the Engineers of the Indian Service to the Royal Engineers in the same year as this magnificent ewer in the Vienna Exhibition 1873.

Likely candidates for the modelling and design who worked closely with the firm Hancock & Co are:

Raffaelle Monti (1818-1881)

The son of the sculptor Gaetano Matteo Monti (1776-1847) of Ravenna and Milan, was something of a prodigy. In his late teens, when he was studying under his father and the sculptor Pompeo Marchesi (1790-1858), a former pupil of Canova, at the Academy of Fine Arts of Brera, Milan, he won several prizes including the Great Gold Medal for his group, 'Alexander Taming Bucephalus.' In 1838, having completed another colossal project, 'Ajax defending the body of Patroculus,' he was invited to go to Vienna to produce various busts for the Imperial family.

Monti's sudden appearance as a widely known celebrity sculptor in the United Kingdom coincided with the display of his work in London at the Great Exhibition of 1851. Before that he had been known in England to only a select group of wealthy patrons, for one of whom, William Cavendish, 6th Duke of Devonshire (1790-1858), he had created in 1847 his celebrated 'Veiled Vestal.

Henry Hugh Armstead RA (1828 – 1905)

Henry Hugh Armstead was born in London in 1828 and received his earliest education in the workshop of his father John, a heraldic chaser. He studied at the Government School of Design at Somerset House from the age of thirteen before attending two privately-run drawing schools.

Armstead was employed by the silversmiths Hunt and Roskell and Hancock &Co while at the same time working in the studio of sculptor Edward Hodges Baily and studying at the Royal Academy Schools. Until around 1863 he concentrated on metalwork, although the lack of recognition he received in this medium led him to turn to sculpture. After his sculptural work was noticed by the Gothic Revival architect George Gilbert Scott, Armstead was employed to create relief panels and other sculptural decorations for buildings including the Palace of Westminster, the Albert Memorial and the Colonial Office (now the Foreign and Commonwealth Office) on Whitehall. His sculpture anticipates the later New Sculpture movement which broadly rejected classicism in favour of realism.

Armstead, who also produced numerous book and magazine illustrations, was elected as a Royal Academician in 1879 (his Diploma Work was a marble relief, The Ever-Reigning Queen). He took an active role in the work of the academy, teaching in the schools for many years and placing the sculpture in many RA exhibitions. He died at his house in London, in 1905.

Both Armstead and Monti together with the architect Owen Jones also produced the ‘Tennyson Vase’ for the Paris 1867 Exhibition for Hancock’s which was purchased at the Exhibition by Napoleon III. The Goodwood Cup of 1866 and Armstead was again involved in the modelling of a Hancock presentation centrepiece commissioned by the Engineers of the Indian Service to the Royal Engineers in the same year as this magnificent ewer in the Vienna Exhibition 1873.

An Exceptional Victorian Ewer 1873 by Charles Frederick Hancocks