BACK TO LIST

BACK TO LIST

The Madame Mère Inkstand

As Masterpiece London 2022 approaches, we would like our customers and friends to discover the Jewel in the Crown of our exhibition: The Madame Mère Inkstand.

The Madame Mère Inkstand

Jean-Baptiste Claude Odiot

Paris, 1812

Paris, 1812

As the name suggests, the Madame Mère inkstand was commissioned by Letizia Ramolino, Napoleon Bonaparte's mother, who later gifted it to her son, King Joseph, in 1812, as testified by the inside documents. 1812, the year of making, is a year of significance as it marks a critical transition in Napoleonic history.

The French Empire was at its greatest extent in 1812.

Having been crowned Emperor of France in 1804, the years between Napoleon's coronation and 1812 are defined by the historians as the years of the Napoleonic wars, as France was in constant conflict with the various European powers in an attempt to conquer them.

On the battlefield, Napoleon experienced enormous success: France defeated the Austrians and the Russians in Austerlitz (1805), Prussia in Jena (1806) and Spain (1808) in the Iberian Peninsula. Then, believing himself invincible, Napoleon launched an offensive in Russia in 1812. However, the venture turned out to be a spectacular failure. In pursuit of the Tsar's army, which continued to retreat eastward, the French were annihilated by the severe Russian cold. Therefore, 1812 marks the peak of Napoleonic grandeur and the last year of the Bonaparte's' fortune, which is well represented by the splendour of this empire-style vermeil inkstand.

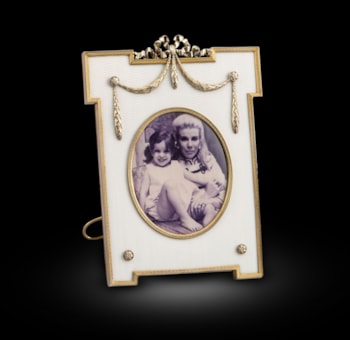

The oblong inkstand rests on four feet modelled as a lion's paws. The main body is decorated on the sides with bees inside wreaths of leaves. The bee was a recurrent symbol of the Empire Style: due to the industrious habits of the insect, Napoleon chose it as the emblem of his power. As a further representation of strength, the large front drawer is embellished with the image of an imperial eagle inside a stylised foliage frieze. The flat top of the inkstand is worked with a delicate flowery flat chasing, which involves hammering with small, blunt tools to give low-relief ornamentation. This technique was highly fashionable for silver decoration in Europe in the early 18th Century. Under the Empire, the ornamental repertoire followed the example of the classical world, whose rigour and perfection Napoleon sincerely appreciated and often commissioned in a presumptuous attempt to emulate the grandeur and splendour of ancient Rome. Therefore, two classical female figures are kneeling on top, each holding a cornucopia, one serving as an inkwell and the other as a pounce pot. The square plinth in the middle, applied with edges of foliage, is surmounted by a pinnacle shaped like an urn, above which sits the imperial eagle. A mechanism inserted inside this element opens a door in the pedestal to reveal a miniature portrait of Letizia Ramolino made by François-Juste-Joseph Sieurac.

The inkstand presents strong similarities with a mustard vase in gilded silver preserved at the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam and made by Odiot. The female figure kneeling next to the jar and the feet in the shape of a lion's paws are almost identical. Furthermore, a salt cellar made by Odiot in gilded bronze and kept at the Musée des Arts Décoratifs in Paris presents an identical design. Moreover, a winged figure similar to the one applied on the plinth door is found in an engraving for a table lamp by Percier and Fontaine, from whose designs Odiot most likely derived many of his ideas.

Letizia Ramolino Bonaparte as Madame Mère

Born in 1750, Maria Letizia was a member of the Ramolino, a noble family of Italian descent who had lived in Corsica for generations.

In 1764, Letizia married Carlo Bonaparte, the son of a local family of similar origins, which ensured her financial security. The family's primary source of income was Carlo Buonaparte's work for Pasquale Paoli, a Corsican patriot, statesman and military leader, head of the resistance movements against the Genoese and French control of the island.

When, in 1768, the French armies landed in Corsica, Paoli's military forces and, therefore, Carlo Bonaparte, were called to fight. Despite being pregnant, Letizia accompanied Carlo to the front line. The event is memorable as, shortly after her return to Ajaccio, Letizia gave birth to her second son, Napoleon; his embryonic attendance on the battlefield contributed to the legend of the most famous character in European history.

On February the 24th, 1785, Carlo Bonaparte died of stomach cancer. Overnight, Letizia became the lady of the house of a destitute family. However, as Napoleon would later state, Letizia "Had a man's brain in a woman's body" and found a way to provide for her family. In 1791, the Archdeacon Lucien, Carlo's uncle, who lived upstairs in Casa Bonaparte, died and left his inheritance to Letizia, granting her a comfortable life and allowing Napoleon to enjoy promotions and starting a career as a Corsican politician.

Napoleon's rise was expeditious, and his fame and wealth were certainly shared and appreciated by Letizia, who received 60,000 francs, which allowed her to move to one of the best residences in Marseille. Although Napoleon provided for her, Letizia remained a dominant and pragmatic woman who never succumbed to the imposing figure of the son. Indeed, Napoleon feared and loved her mother in equal measure.

For instance, immediately after his imperial ascent, Napoleon granted his family titles, including "Prince of the Empire", to Joseph and Louis. However, Letizia was so upset about her "Madame Mère" - that she decided to boycott Napoleon's coronation by not attending.

To correct the wrong suffered by Napoleon, the painter Jacques-Louis David decided to insert Letizia in the famous representation of his coronation, now housed in the Louvre, representing her smiling as she watches her son ascending to the throne of France.

Jean-Baptiste Claude Odiot

Jean Baptiste Claude was born in 1763 in Paris, France. He was a determined, independent, and stubborn young man who dreamed of serving his country as a soldier. By the age of 16, he had enrolled in the army already. His father, Jean Claude, would have liked one of his sons to inherit the Maison Odiot company which was founded in 1690 by his father. However, his children had different plans at the time, and Jean Baptiste was too distracted by the dream of becoming a general.

Still, soon enough, the long military campaigns, the distance from home and the failures led Odiot’s enthusiasm for the army to fade, and he started the apprenticeship with his father.

On the 14th of December 1788, Jean Claude died after working side by side with his son for approximately two years. At the age of 22, Odiot found himself at the head of a goldsmith company during one of the most uncertain economic periods in the history of France. It was the prelude to the French Revolution, and vast quantities of silver were melted to meet the pressing demand from the army. Therefore, most goldsmiths had to reinvent themselves by producing ammunition or military badges.

Jean Baptiste was one of the few goldsmiths in Paris to refuse to work for the army and decided to accept commissions from foreign collectors to continue a creative production instead. The long list of Odiot customers from this period included Thomas Jefferson, the third president of the United States and signer of the American declaration of independence. It was a prosperous period, albeit a relatively short one. In fact, on 15th September 1792, Paris passed a law banning the export of silver and other metals abroad. Many customers left the country in a few months, leaving debts to pay, thus condemning goldsmiths to bankruptcy. Fortunately, the Odiot family survived thanks to the possessions and sufficient fortunes accumulated in the previous decades.

The French Revolution officially began, and Paris was torn apart by riots. Although not a revolutionary, Jean Baptiste was a man of action and joined the battles to serve France. According to historical sources, on the door of the Maison Odiot workshop, a sign would read: "this goldsmith is fighting the enemies of the fatherland".

In 1792, Luis XVI and Marie Antoinette were sentenced to death while Napoleon began his brilliant ascent. It is almost certain that, during the years of the revolts, Jean Baptiste had seen Napoleon in action, although the goldsmith could never have imagined that that young and thin general would have determined his fortune and his success in a few years.

Once back in Paris, Odiot continued his goldsmith business in parallel with three other great names in goldsmithing in Paris: Roetties, Auguste and Cornu. Although the latter's style, influenced mainly by neoclassicism, was highly appreciated in the city, and their talent was enormous, Odiot belonged to the new generation of emerging artists. Odiot's talent and innovation involved many private commissions, which increased enormously following 1801 when he won a gold medal at the second Exhibition of French Industry Products in Paris. The gold medal also attracted the attention of Napoleon, who invited the 24 winners to a competition to expand the silver collection at the Tuileries Palace. Despite the meeting, official commissions arrived only after 1804 with the official coronation of Napoleon as Emperor.

Napoleon played a vital role in developing what will be termed by the Empire Style by art historians in France. The emperor became a patron of the arts during the years of his reign. He fostered the careers of numerous artists who catered to his desire for classicism in a presumptuous attempt to emulate the grandeur and splendour of ancient Rome. In the context of silverware, the artists who enjoyed the emperor’s attention were Biennais, Auguste and, indeed, Odiot.

The number of employees grew to such an extent that, around 1805, Biennais' workshop had approximately 600 employees, historians estimate. Therefore, it is not surprising why Odiot, despite his success, nevertheless decided to join forces with the other two great names of the goldsmith in Paris: Biennais and Auguste. Despite the latter's fame, Odiot was the true star and the creator of all the major orders the group received. From 1806 onwards, Odiot's career became unstoppable. Odiot began to receive essential orders from Europe, where the new king of Bavaria, Maximilien I, required the French talent for his collection of gold and silver. According to historians, there is not a figure among those who shaped Nineteenth-Century history who was not a client of Odiot at some point.

Odiot became one of the most prolific and successful exponents of the Empire style, which crystallised under the reign of Napoleon I. However, the genesis of this style can be traced back to the 1770s with the production of Jean-Vincent Huguet or to the foliage friezes of Antoine Boullier. Furthermore, the success of the designs of Percier, Fontaine and Prud'Hon certainly favoured the development of the Empire, a much more severe style than that of Louis XVI.