BACK TO LIST

BACK TO LIST

Graceful Vessels for Wine

The first table wine coolers were made in the closing years of the 17th century with the use of the wine cistern slowly being superseded. The need for a single bottle cooler was felt, probably at first on those rare occasions when the master of the great house was dining alone. These were two-handled and vase-shaped having a detachable collar and liner to hold back the ice and to allow for the free insertion of the bottle.

Usually made in pairs or occasionally in sets of four, wine coolers were substantial objects, and were intended as much for display as for use. The 19th century saw this vase-shaped form develop with prevailing fashionable details varying in everything from Rococo to Gothic architecture.

The difference with Paul Storr, at first with Rundell, Bridge and Rundell from 1807-1819 and after with Storr & Mortimer and other outlets for luxury goods was startling: instead of patrons dictating the type of goods he or she required and what they should look like, Storr determined what the client should buy.

The full ornamental value of twisting vine tendrils, spreading shaped leaves and fleshy bunches of grapes and the modelling of such with a Bacchic theme would have been a standard part of an apprentice artisans training from the seventeenth to the nineteenth century. With wonderful architects and artists employed to design new items. The likes of William Theed R.A, Thomas Stothard R.A, John Flaxman, the influences of James "Athenian" Stuart and Edward Hodges Baily were just a few of the great minds helping Paul Storr achieve the wonders that finally graced the table as a wine cooler.

We are proud to present a selection of these elegant, superbly detailed and beautiful vessels that graced the tables of the great houses here in England. All bearing that magical goldsmith’s signature of Paul Storr.

The Earl of Caledon’s Wine Coolers

A Magnificent Pair of George III Wine Coolers

London, 1809

Maker's mark of Paul Storr

Weight: 232.88 ozs, (7,242g)

Height: 9.25in, (23.5cm)

Bearing the coats-of-arms of Du Pré Alexander, 2nd Earl of Caledon.

These wine coolers in imperial style are of urn shape, with detachable capes and interior liners. The capes with shell, gadroon and palmette borders, the main body half-fluted with a single plain band. The two reeded handles with cast shell and foliate decoration, terminating in lion’s head mask. The coolers resting on four lion’s paw feet raised on an alter pedestal. Each side with the family coat-of-arms and engraved with the family motto, "PER MARE PER TERRAS"

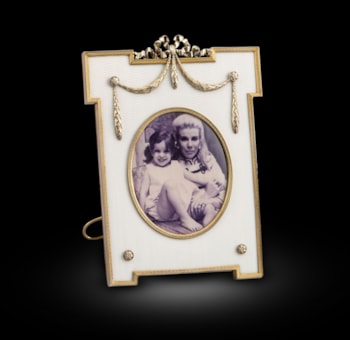

The 2nd Earl of Caledon, engraved by Charles Turner from a portrait by Richard Rothwell

Du Pré Alexander, 2nd Earl of Caledon KP. (14 December 1777 – 8 April 1839)

Styled the Honourable Du Pré Alexander from 1790 to 1800 and Viscount Alexander from 1800 to 1802, was an Irish peer, landlord and colonial administrator, and was the second child and only son of James Alexander, 1st Earl of Caledon

He was educated from 1790 to 1796 at Eton College in England and later at Christ Church, Oxford. He was elected Member of Parliament for Newtownards in 1800 and sat in the Irish House of Commons until the Act of Union in 1801. In the latter year, he was appointed High Sheriff of Armagh.[1] He succeeded to the title of Earl of Caledon on the death of his father in 1802 and was elected a Representative Peer for Ireland in 1804.

In July 1806 he was appointed Governor of the Cape of Good Hope in what is now South Africa. He was the first governor on the Cape's cession to United Kingdom; the Caledon River and the district Caledon, Western Cape there are named after him. Lord Caledon was not, literally, the first British civil governor of the Cape, having been preceded in that capacity by Lord Macartney and Sir George Yonge, successive holders of the office between the first conquest of the Cape, and its cession back to the Dutch under the terms of the Peace of Amiens of 1802. Rather, Lord Caledon was the first civil governor after the Cape's reconquest from the Dutch by General Sir David Baird in 1806. The question of the relationship between the civil and the military authorities of the colony, personified in Lord Caledon's relationship with the Commander-in-Chief, General Sir Henry Grey, was the most troublesome of the former's period of office as governor, and the issue on which he resigned in June 1811.

Less than three years after his departure, in March 1814, an open letter was written defending his record as governor. The writer, Colonel Christopher Bird, Deputy Colonial Secretary at the Cape (subsequently Colonial Secretary), was well qualified to speak, although his partisanship on Lord Caledon's behalf is unconcealed. In another part of the Caledon Papers, Lord Caledon's own appraisal of his governorship of the Cape is to be found. It occurs in the course of a letter which he wrote to the Prime Minister, the 2nd Earl of Liverpool, in 1818 stating his claims to be given a peerage of the United Kingdom: '... The administration of the colonial government during my residence there for a term of four years, was more than usually arduous, in consequence of my being the first civil governor after the capture of the settlement, and from there being no records of a former British government in any of the public offices at The Cape. ... I hope I shall be excused for stating that, upon my own responsibility and under the most embarrassing circumstances, occasioned by the loss of four British frigates which were to have protected the convoy, I detached 2,000 infantry to co-operate with the force from India in the reduction of the Mauritius. In a letter from Lord Minto [Governor General of India] upon that occasion, he acknowledges the public service I rendered, not only as relating to the fall of the Mauritius, but adds that it was to the co-operation I afforded he was indebted for the means of moving against Java. ...'.[2]

Lord Caledon married Lady Catherine Yorke, daughter of Philip Yorke, 3rd Earl of Hardwicke and Lady Elizabeth Lindsay, on 16 October 1811 in St. James' Church, Westminster, and had issue:

James Du Pre Alexander, 3rd Earl of Caledon (27 July 1812 – 30 June 1855)

With this marriage the Caledon family effectively inherited Tyttenhanger House near St Albans, Hertfordshire, which had belonged to the 3rd Earl of Hardwicke's grandmother, Katherine Freeman, the sister and heiress of Sir Henry Pope Blount, 3rd and last Baronet.[2] Sir Henry died in 1757 without issue, leaving his sister Katherine, the wife of Rev. William Freeman, his heir. She left an only daughter, Catherine, who married Charles Yorke, second son of Philip Yorke, 1st Earl of Hardwicke, whose son Philip, 3rd Earl of Hardwicke, on his death in 1834, left four daughters, to the second of whom, Catherine, the wife of the 2nd Earl of Caledon, came the manor of Tyttenhanger.

Lord Caledon was invested as a Knight of St Patrick on 20 August 1821 and was appointed Lord Lieutenant of County Tyrone in 1831. He died on 8 April 1839 at Caledon, aged 61, much mourned by his tenants in the model town of Caledon, which he had rebuilt and enlarged so sympathetically. A loyal address from the tenantry issued a few years earlier alludes to his 'acts of liberality, munificence and kindness' and there is plenty of evidence to confirm that this was no mere empty elegy. 'Lord Caledon', wrote Inglis in his book Ireland (1834), 'is all that could be desire – a really good resident country gentleman'.[3]

Lady Caledon died on 8 July 1863, having bequeathed Tyttenhanger to her daughter-in-law Jane, with an entail upon her four children and, according to one source, the estate descended to her eldest son James Alexander, 4th Earl of Caledon, who died in 1898. His widow became lady of the manor and held it in trust for her children.[4] Other sources indicate that Tyttenhanger was the home of Lady Jane Van Koughnet, the daughter of the 4th Earl of Caledon, and her husband, Commander E. B. Van Koughnet, until her death in 1941.[5] The house was sold in 1973.

References:

1. Stuart, John (1819). Historical Memoirs of The City of Armagh. Newry: Alexander Wilkinson. p. 557.

2. Summary of the Caledon Papers, Public Record Office of Northern Ireland, A. P. W. Malcomson

3. Great Houses of Ireland, Hugh Montgomery-Massingberd and Christopher Simon Sykes (Laurence King, London 1999)

4. A History of the County of Hertford: volume 2, 1908, found at http://www.british-history.ac.uk/report.asp?compid=43299

5. Hertfordshire County Homes, found at http://www.hertfordshire-genealogy.co.uk/data/books/books-3/book-0325-herts-county- homes.htm

The Earl of Coventry’s Wine Coolers

A Magnificent Set of Four George III Wine Coolers

London, 1810

With maker’s mark of Paul Storr

Retailed by Rundell, Bridge and Rundell

Height: 11 5/8 in. 29.5 cm

Weight: 21,894 g, 703 oz 19 dwt

Bearing the coat-of-arms of the Earl of Coventry

This form of wine cooler is based on the Roman Medici Krater but some of the decoration has been replaced by the splendid cast and applied coats-of-arms of the Earl of Coventry. The lower bodies cast in sections and applied with palm and acanthus spaced with grapes and cornucopias above square bases. The capes with egg and dart rims above applied grapevine. The stippled bodies with applied cast contemporary arms, supporters and coronets. The reeded handles rising from bearded Bacchic masks and backed by large anthemia. The base rims with the Latin signature of Rundell, Bridge & Rundell and numbered 406.

The arms are those of Coventry, for George 7th Earl of Coventry 1758-1831, who succeeded to the title in 1809. His father, the 6th Earl, who married one of the Gunning sisters, famous for their beauty, updated Croome Court in Worcestershire with the help of Capability Brown and Robert Adam. It was Brown’s first project, started in 1751 and called by him “his first and most favourite child”. Adam was brought to the house in 1760 and his long gallery is thought to be the first complete example of his work. Both remained friends with the Earl who was a pall bearer at Adam’s funeral. The tapestry room (Gobelins) is now installed in the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Baron Roberts Wine Coolers

A Pair of 19th Century Regency Wine Coolers

By Paul Storr

London, 1812

Weight: 9300 g, 299 oz

Bearing the coat-of-arms of Baron Roberts

The wine coolers on square pedestal feet with urn shaped collets rising to the main krater-shaped bodies. The base of the body with fluting with an ovolo band. The entire bodies stippled with cast and applied coats-of-arms to either side for the Roberts family. The tops of the main body with cast and applied grapes and vines following all the way round and sprouting from the bifurcated vine branch handles. The capes with a cast laurel border, the coolers also with their original silver liners.

A Pair of 19th Century George III Wine Cooler on Stands.

London, 1819

Maker’s mark of Paul Storr

Weight: 367 oz 6 dwt

Height: 26.7 cm, 10.5 in

The design of this magnificent pair of wine coolers on stands is attributed to Edward Hodges Baily. The wine coolers on circular stands with shell, acanthus and palmette borders. The bases also fluted and rising to a platform with a band of scrolling acanthus. The coolers on four scrolled shell feet with a cast and applied spray of oak leaf and acorn rising up the body of the cooler above the shells. The main bodies fluted and terminating at the collar with a contrasting plain convex band. The reeded handles bound and terminating on the main body with acanthus leaves. The capes with a matching border of shell, acanthus and palmette border to the base. The coolers also with their original silver liners.

Literature:

For comparison, Paul Storr, 1771-1844: Silversmith and Goldsmith by Norman M. Penzer.

A Pair of Geo IV Warwick Vase Wine Coolers

London, 1821

Maker’s mark of Paul Storr

Weight: 6,740 g, 216 oz 14 dwt

Height: 19.5 cm, 7.7 in

The Warwick Vase is an ancient Roman marble vase with Bacchic ornament that was discovered at Hadrian's Villa, Tivoli about 1771 by Gavin Hamilton, a Scottish painter-antiquarian and art dealer in Rome, and is now in the Burrell Collection near Glasgow in Scotland. The vase was found in the silt of a marshy pond at the low point of the villa's extensive grounds, where Hamilton had obtained excavation rights and proceeded to drain the area. Hamilton sold the fragments to Sir William Hamilton, British envoy at the court of Naples from whose well-known collection it passed to his nephew George Greville, 2nd Earl of Warwick, where it caused a sensation.

Restoration of the Vase

The design and much of the ornament is Roman, of the second century CE, but the extent to which the fragments were restored and completed after its discovery, to render it a fit object for a connoisseur's purchase, may be judged from Sir William Hamilton's own remark "I was obliged to cut a block of marble at Carrara to repair it, which has been hollowed out & the fragments fixed on it, by which means the vase is as firm & entire as the day it was made." Needless to say, Sir William did not visit Carrara to hew the block himself. The connoisseur-dealer James Byres's role in shaping the present allure of the Warwick Vase is not generally noted: "The great Vase is nearly finished and I think comes well. I beg'd of Mr. Hamilton to go with me the other day to give his opinion. He approved much of the restoration but thought the female mask copied from that in Piranesi's candelabro ought to be a little retouch'd to give more squareness and character, he's of opinion that the foot ought neither to be fluted nor ornamented but left as it is being antique, and that no ornament ought to be introduced on the body of the vase behind the handles, saying that it would take away from the effect & grouping of the masks. Piranesi is of the same opinion relative to the foot but thinks there is too great an emptyness behind the handles.... It's difficult to say which of these opinions ought to be followed, but I rather lean toward Mr. Hamiltons." Thus it appears James Byres rather than Giovanni Battista Piranesi was put in charge of the vase's restoration and completion. Piranesi made two etchings of the vase as completed, dedicated to Sir William, which were included in his 1778 publication, Vasi, candelabri, cippi..." which secured its reputation and should have added to its market desirability. Sir William apparently hoped to sell it to the British Museum, which had purchased his collection of "Etruscan" vases: "Keep it I cannot, as I shall never have a house big enough for it", he wrote.

On display at the Burrell Collection near Glasgow

Usually made in pairs or occasionally in sets of four, wine coolers were substantial objects, and were intended as much for display as for use. The 19th century saw this vase-shaped form develop with prevailing fashionable details varying in everything from Rococo to Gothic architecture.

The difference with Paul Storr, at first with Rundell, Bridge and Rundell from 1807-1819 and after with Storr & Mortimer and other outlets for luxury goods was startling: instead of patrons dictating the type of goods he or she required and what they should look like, Storr determined what the client should buy.

The full ornamental value of twisting vine tendrils, spreading shaped leaves and fleshy bunches of grapes and the modelling of such with a Bacchic theme would have been a standard part of an apprentice artisans training from the seventeenth to the nineteenth century. With wonderful architects and artists employed to design new items. The likes of William Theed R.A, Thomas Stothard R.A, John Flaxman, the influences of James "Athenian" Stuart and Edward Hodges Baily were just a few of the great minds helping Paul Storr achieve the wonders that finally graced the table as a wine cooler.

We are proud to present a selection of these elegant, superbly detailed and beautiful vessels that graced the tables of the great houses here in England. All bearing that magical goldsmith’s signature of Paul Storr.

The Earl of Caledon’s Wine Coolers

A Magnificent Pair of George III Wine Coolers

London, 1809

Maker's mark of Paul Storr

Weight: 232.88 ozs, (7,242g)

Height: 9.25in, (23.5cm)

Bearing the coats-of-arms of Du Pré Alexander, 2nd Earl of Caledon.

These wine coolers in imperial style are of urn shape, with detachable capes and interior liners. The capes with shell, gadroon and palmette borders, the main body half-fluted with a single plain band. The two reeded handles with cast shell and foliate decoration, terminating in lion’s head mask. The coolers resting on four lion’s paw feet raised on an alter pedestal. Each side with the family coat-of-arms and engraved with the family motto, "PER MARE PER TERRAS"

The 2nd Earl of Caledon, engraved by Charles Turner from a portrait by Richard Rothwell

Du Pré Alexander, 2nd Earl of Caledon KP. (14 December 1777 – 8 April 1839)

Styled the Honourable Du Pré Alexander from 1790 to 1800 and Viscount Alexander from 1800 to 1802, was an Irish peer, landlord and colonial administrator, and was the second child and only son of James Alexander, 1st Earl of Caledon

He was educated from 1790 to 1796 at Eton College in England and later at Christ Church, Oxford. He was elected Member of Parliament for Newtownards in 1800 and sat in the Irish House of Commons until the Act of Union in 1801. In the latter year, he was appointed High Sheriff of Armagh.[1] He succeeded to the title of Earl of Caledon on the death of his father in 1802 and was elected a Representative Peer for Ireland in 1804.

In July 1806 he was appointed Governor of the Cape of Good Hope in what is now South Africa. He was the first governor on the Cape's cession to United Kingdom; the Caledon River and the district Caledon, Western Cape there are named after him. Lord Caledon was not, literally, the first British civil governor of the Cape, having been preceded in that capacity by Lord Macartney and Sir George Yonge, successive holders of the office between the first conquest of the Cape, and its cession back to the Dutch under the terms of the Peace of Amiens of 1802. Rather, Lord Caledon was the first civil governor after the Cape's reconquest from the Dutch by General Sir David Baird in 1806. The question of the relationship between the civil and the military authorities of the colony, personified in Lord Caledon's relationship with the Commander-in-Chief, General Sir Henry Grey, was the most troublesome of the former's period of office as governor, and the issue on which he resigned in June 1811.

Less than three years after his departure, in March 1814, an open letter was written defending his record as governor. The writer, Colonel Christopher Bird, Deputy Colonial Secretary at the Cape (subsequently Colonial Secretary), was well qualified to speak, although his partisanship on Lord Caledon's behalf is unconcealed. In another part of the Caledon Papers, Lord Caledon's own appraisal of his governorship of the Cape is to be found. It occurs in the course of a letter which he wrote to the Prime Minister, the 2nd Earl of Liverpool, in 1818 stating his claims to be given a peerage of the United Kingdom: '... The administration of the colonial government during my residence there for a term of four years, was more than usually arduous, in consequence of my being the first civil governor after the capture of the settlement, and from there being no records of a former British government in any of the public offices at The Cape. ... I hope I shall be excused for stating that, upon my own responsibility and under the most embarrassing circumstances, occasioned by the loss of four British frigates which were to have protected the convoy, I detached 2,000 infantry to co-operate with the force from India in the reduction of the Mauritius. In a letter from Lord Minto [Governor General of India] upon that occasion, he acknowledges the public service I rendered, not only as relating to the fall of the Mauritius, but adds that it was to the co-operation I afforded he was indebted for the means of moving against Java. ...'.[2]

Lord Caledon married Lady Catherine Yorke, daughter of Philip Yorke, 3rd Earl of Hardwicke and Lady Elizabeth Lindsay, on 16 October 1811 in St. James' Church, Westminster, and had issue:

James Du Pre Alexander, 3rd Earl of Caledon (27 July 1812 – 30 June 1855)

With this marriage the Caledon family effectively inherited Tyttenhanger House near St Albans, Hertfordshire, which had belonged to the 3rd Earl of Hardwicke's grandmother, Katherine Freeman, the sister and heiress of Sir Henry Pope Blount, 3rd and last Baronet.[2] Sir Henry died in 1757 without issue, leaving his sister Katherine, the wife of Rev. William Freeman, his heir. She left an only daughter, Catherine, who married Charles Yorke, second son of Philip Yorke, 1st Earl of Hardwicke, whose son Philip, 3rd Earl of Hardwicke, on his death in 1834, left four daughters, to the second of whom, Catherine, the wife of the 2nd Earl of Caledon, came the manor of Tyttenhanger.

Lord Caledon was invested as a Knight of St Patrick on 20 August 1821 and was appointed Lord Lieutenant of County Tyrone in 1831. He died on 8 April 1839 at Caledon, aged 61, much mourned by his tenants in the model town of Caledon, which he had rebuilt and enlarged so sympathetically. A loyal address from the tenantry issued a few years earlier alludes to his 'acts of liberality, munificence and kindness' and there is plenty of evidence to confirm that this was no mere empty elegy. 'Lord Caledon', wrote Inglis in his book Ireland (1834), 'is all that could be desire – a really good resident country gentleman'.[3]

Lady Caledon died on 8 July 1863, having bequeathed Tyttenhanger to her daughter-in-law Jane, with an entail upon her four children and, according to one source, the estate descended to her eldest son James Alexander, 4th Earl of Caledon, who died in 1898. His widow became lady of the manor and held it in trust for her children.[4] Other sources indicate that Tyttenhanger was the home of Lady Jane Van Koughnet, the daughter of the 4th Earl of Caledon, and her husband, Commander E. B. Van Koughnet, until her death in 1941.[5] The house was sold in 1973.

References:

1. Stuart, John (1819). Historical Memoirs of The City of Armagh. Newry: Alexander Wilkinson. p. 557.

2. Summary of the Caledon Papers, Public Record Office of Northern Ireland, A. P. W. Malcomson

3. Great Houses of Ireland, Hugh Montgomery-Massingberd and Christopher Simon Sykes (Laurence King, London 1999)

4. A History of the County of Hertford: volume 2, 1908, found at http://www.british-history.ac.uk/report.asp?compid=43299

5. Hertfordshire County Homes, found at http://www.hertfordshire-genealogy.co.uk/data/books/books-3/book-0325-herts-county- homes.htm

The Earl of Coventry’s Wine Coolers

A Magnificent Set of Four George III Wine Coolers

London, 1810

With maker’s mark of Paul Storr

Retailed by Rundell, Bridge and Rundell

Height: 11 5/8 in. 29.5 cm

Weight: 21,894 g, 703 oz 19 dwt

Bearing the coat-of-arms of the Earl of Coventry

This form of wine cooler is based on the Roman Medici Krater but some of the decoration has been replaced by the splendid cast and applied coats-of-arms of the Earl of Coventry. The lower bodies cast in sections and applied with palm and acanthus spaced with grapes and cornucopias above square bases. The capes with egg and dart rims above applied grapevine. The stippled bodies with applied cast contemporary arms, supporters and coronets. The reeded handles rising from bearded Bacchic masks and backed by large anthemia. The base rims with the Latin signature of Rundell, Bridge & Rundell and numbered 406.

The arms are those of Coventry, for George 7th Earl of Coventry 1758-1831, who succeeded to the title in 1809. His father, the 6th Earl, who married one of the Gunning sisters, famous for their beauty, updated Croome Court in Worcestershire with the help of Capability Brown and Robert Adam. It was Brown’s first project, started in 1751 and called by him “his first and most favourite child”. Adam was brought to the house in 1760 and his long gallery is thought to be the first complete example of his work. Both remained friends with the Earl who was a pall bearer at Adam’s funeral. The tapestry room (Gobelins) is now installed in the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Baron Roberts Wine Coolers

A Pair of 19th Century Regency Wine Coolers

By Paul Storr

London, 1812

Weight: 9300 g, 299 oz

Bearing the coat-of-arms of Baron Roberts

The wine coolers on square pedestal feet with urn shaped collets rising to the main krater-shaped bodies. The base of the body with fluting with an ovolo band. The entire bodies stippled with cast and applied coats-of-arms to either side for the Roberts family. The tops of the main body with cast and applied grapes and vines following all the way round and sprouting from the bifurcated vine branch handles. The capes with a cast laurel border, the coolers also with their original silver liners.

A Pair of 19th Century George III Wine Cooler on Stands.

London, 1819

Maker’s mark of Paul Storr

Weight: 367 oz 6 dwt

Height: 26.7 cm, 10.5 in

The design of this magnificent pair of wine coolers on stands is attributed to Edward Hodges Baily. The wine coolers on circular stands with shell, acanthus and palmette borders. The bases also fluted and rising to a platform with a band of scrolling acanthus. The coolers on four scrolled shell feet with a cast and applied spray of oak leaf and acorn rising up the body of the cooler above the shells. The main bodies fluted and terminating at the collar with a contrasting plain convex band. The reeded handles bound and terminating on the main body with acanthus leaves. The capes with a matching border of shell, acanthus and palmette border to the base. The coolers also with their original silver liners.

Literature:

For comparison, Paul Storr, 1771-1844: Silversmith and Goldsmith by Norman M. Penzer.

A Pair of Geo IV Warwick Vase Wine Coolers

London, 1821

Maker’s mark of Paul Storr

Weight: 6,740 g, 216 oz 14 dwt

Height: 19.5 cm, 7.7 in

The Warwick Vase is an ancient Roman marble vase with Bacchic ornament that was discovered at Hadrian's Villa, Tivoli about 1771 by Gavin Hamilton, a Scottish painter-antiquarian and art dealer in Rome, and is now in the Burrell Collection near Glasgow in Scotland. The vase was found in the silt of a marshy pond at the low point of the villa's extensive grounds, where Hamilton had obtained excavation rights and proceeded to drain the area. Hamilton sold the fragments to Sir William Hamilton, British envoy at the court of Naples from whose well-known collection it passed to his nephew George Greville, 2nd Earl of Warwick, where it caused a sensation.

Restoration of the Vase

The design and much of the ornament is Roman, of the second century CE, but the extent to which the fragments were restored and completed after its discovery, to render it a fit object for a connoisseur's purchase, may be judged from Sir William Hamilton's own remark "I was obliged to cut a block of marble at Carrara to repair it, which has been hollowed out & the fragments fixed on it, by which means the vase is as firm & entire as the day it was made." Needless to say, Sir William did not visit Carrara to hew the block himself. The connoisseur-dealer James Byres's role in shaping the present allure of the Warwick Vase is not generally noted: "The great Vase is nearly finished and I think comes well. I beg'd of Mr. Hamilton to go with me the other day to give his opinion. He approved much of the restoration but thought the female mask copied from that in Piranesi's candelabro ought to be a little retouch'd to give more squareness and character, he's of opinion that the foot ought neither to be fluted nor ornamented but left as it is being antique, and that no ornament ought to be introduced on the body of the vase behind the handles, saying that it would take away from the effect & grouping of the masks. Piranesi is of the same opinion relative to the foot but thinks there is too great an emptyness behind the handles.... It's difficult to say which of these opinions ought to be followed, but I rather lean toward Mr. Hamiltons." Thus it appears James Byres rather than Giovanni Battista Piranesi was put in charge of the vase's restoration and completion. Piranesi made two etchings of the vase as completed, dedicated to Sir William, which were included in his 1778 publication, Vasi, candelabri, cippi..." which secured its reputation and should have added to its market desirability. Sir William apparently hoped to sell it to the British Museum, which had purchased his collection of "Etruscan" vases: "Keep it I cannot, as I shall never have a house big enough for it", he wrote.

The Vase at Warwick Castle

Disappointed by the British Museum, Hamilton shipped the fully restored vase to his elder nephew, George Greville, 2nd Earl of Warwick, who set it at first on a lawn at Warwick Castle, but with the intention of preserving it from the British climate, he commissioned a special greenhouse for it, fitted, however, with Gothic windows, from a local architect at Warwick, William Eboral: "I built a noble greenhouse, and filled it with beautiful plants. I placed in it a vase, considered as the finest remains of Grecian art extant for size and beauty. "The vase was displayed on a large plinth, which remains with it in the Burrell Collection, where it is also displayed in a courtyard-like setting inside the building, surrounded by miniature fig trees. The vase was widely admired and much visited in the Earl's greenhouse, but he permitted no full-size copies to be made of it, until moulds were made at the special request of Lord Lonsdale, who intended to have a full-size replica cast— in silver. The sculptor William Theed the elder, who was working for the Royal silversmiths Rundell, Bridge & Rundell, was put in charge of the arrangements, but Lord Lonsdale changed his mind, and a project truly of Imperial Russian scale was aborted. (Please see Christopher Hartop’s Royal Goldsmiths: The art of Rundell & Bridge page 117 for a more accurate account). The rich ornament, and the form, which is echoed in sixteenth-century Mannerist vases, combined to give the Warwick Vase great appeal to the nineteenth-century eye: numerous examples in silver and bronze were made, and porcelain versions by Rockingham and Worcester. Theed's moulds were sent to Paris, where two full-size bronze replicas were cast, one now Windsor Castle, the other in the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge. Reduced versions in cast-iron continue to be manufactured as garden ornaments, and in these ways the Warwick Vase took up a place in the visual repertory of classical design. It was even the model for the silver-gilt tennis trophy, the Norman Brookes Challenge Cup won at the Australian Open.

Disappointed by the British Museum, Hamilton shipped the fully restored vase to his elder nephew, George Greville, 2nd Earl of Warwick, who set it at first on a lawn at Warwick Castle, but with the intention of preserving it from the British climate, he commissioned a special greenhouse for it, fitted, however, with Gothic windows, from a local architect at Warwick, William Eboral: "I built a noble greenhouse, and filled it with beautiful plants. I placed in it a vase, considered as the finest remains of Grecian art extant for size and beauty. "The vase was displayed on a large plinth, which remains with it in the Burrell Collection, where it is also displayed in a courtyard-like setting inside the building, surrounded by miniature fig trees. The vase was widely admired and much visited in the Earl's greenhouse, but he permitted no full-size copies to be made of it, until moulds were made at the special request of Lord Lonsdale, who intended to have a full-size replica cast— in silver. The sculptor William Theed the elder, who was working for the Royal silversmiths Rundell, Bridge & Rundell, was put in charge of the arrangements, but Lord Lonsdale changed his mind, and a project truly of Imperial Russian scale was aborted. (Please see Christopher Hartop’s Royal Goldsmiths: The art of Rundell & Bridge page 117 for a more accurate account). The rich ornament, and the form, which is echoed in sixteenth-century Mannerist vases, combined to give the Warwick Vase great appeal to the nineteenth-century eye: numerous examples in silver and bronze were made, and porcelain versions by Rockingham and Worcester. Theed's moulds were sent to Paris, where two full-size bronze replicas were cast, one now Windsor Castle, the other in the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge. Reduced versions in cast-iron continue to be manufactured as garden ornaments, and in these ways the Warwick Vase took up a place in the visual repertory of classical design. It was even the model for the silver-gilt tennis trophy, the Norman Brookes Challenge Cup won at the Australian Open.

On display at the Burrell Collection near Glasgow

After it was sold in London in 1978 and purchased by the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the Warwick Vase was declared an object of national importance, and an export license was delayed. Matching funds were raised, and, as it was not of sufficient archaeological value for the British Museum, it found a sympathetic home at the Burrell Collection, Glasgow.