Trade cards, billheads, advertisements, newspaper reports and existing examples of silver and silver-gilt are abundant evidence that the early 19th century London goldsmith, Thomas Hamlet counted among his customers members of the British royal family. George, Prince of Wales, later George IV, Frederick Augustus, Duke of York and their sisters, the Princesses Augusta, Elizabeth, Mary and Sophia were all purchasers at his shop in Princes Street, Leicester Square.

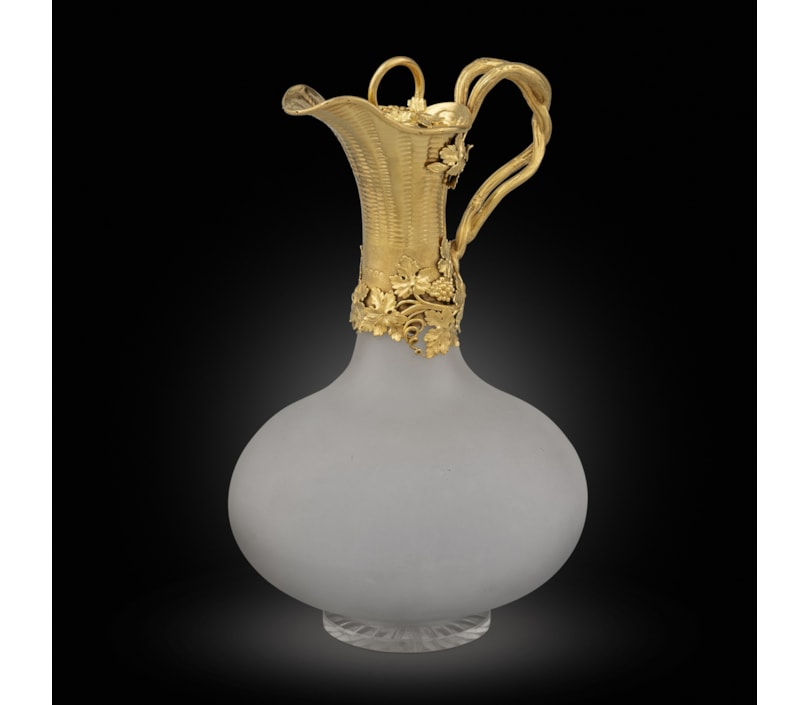

Thomas Hamlet was Goldsmith to the King. Hamlet’s principal silversmith during the most fruitful years of his career was William Elliott of Clerkenwell and it is the latter’s mark which is struck on the mounts of this flask. Moreover, while the design of Elliott’s mounts, particularly the shape of the screw-on cover, nods in the direction of China as befits the flask itself, the silversmith was actually looking for his inspiration at a pair of late 17th century silver flasks, George Garthorne, London, 1690, which were then owned by the Duke of York. These were acquired in 1827 by George IV and are now in the royal collection, presently on view in the Lantern Lobby, Windsor Castle. Elliott (and therefore Hamlet) knew of the Garthorne flasks as early as 1823 when he copied them for the Peel family of Drayton Manor, Staffordshire, one of whom was Sir Robert Peel (1788-1850), Home Secretary from 1822 to 1827 and Prime Minister in 1834/35 and from 1841 to 1846.

William Elliott (1773-1855) is listed as the manufacturing silversmith of 25 Compton Street, Clerkenwell. The lack of any substantial information about him and his workshop in no way diminishes the exceptional quality of much of the surviving silver and silver-gilt which bears his mark. As in the retail/manufacturer relationships which existed between Rundell, Bridge & Rundell and Paul Storr and Kensington Lewis and Edward Farrell, there is good evidence to suggest that Elliott was chief supplier of new plate to the goldsmith and jeweller, Thomas Hamlet (1770-1853).

William Elliott, who was born on 22 March 1773 and baptized at St. James’s, Piccadilly on 6 April following, was the eldest child of William Elliott and his wife, Rebecca.6 At the age of 14 in May 1787 he was apprenticed to Richard Gardner, Citizen and Goldsmith, of Silver Street, Golden Square, Soho, when his father was described as ‘of Warwick Lane London plate worker.’

Richard Gardner (active ?1745-?1795) had been apprenticed in 1745 to William Cripps (1715-1766), a prominent London manufacturing and retail silversmith of the middle of the 18th century, who in turn was apprenticed in 1731 to the Huguenot goldsmith, David Willaume (1658-1741).

Elliott gained his freedom of the Goldsmiths’ Company upon completing his apprenticeship on 1 April 1795. In 1799 he was recorded as of Warwick Lane (not to be confused with his father at the same address) when he took John Angell, brother of Joseph Angell, as apprentice.

Although for the next ten and a half years Elliott disappears from view, he was married and had two children: Richard William (1805?-1866) and Jane Rebecca (1805?-1860). The next firm date found for him is 6 October 1809, when he entered his first mark in partnership with Joseph William Story (1781?-1864), from 25 Compton Street, Clerkenwell.

A former apprentice of the smallworker Abstainando King (1764-1833), Story dissolved his partnership with Elliott in 1813. Story is then discovered as a silversmith in Southwark on 8 July 1821 when one of his daughters, Ann Sarah was christened at St. Saviour. On 28 December 1830, Story, his wife, Mary (née Gilbert), their six children and Mr. and Mrs. Gilbert arrived at Hobart Town, Tasmania on board the ship ‘Mary.’ Unlike the London silversmith Thomas Wimbush (1805/06-1869), however, who was transported to the island at Her Majesty’s pleasure in 1849, Story’s emigration was voluntary.

William Elliott remained at 25 Compton Street for the rest of his working life. Among his apprentices there were Charles Fry (d. 1826) and his brother, John (d. 1859). Subsequently also working in Clerkenwell, the Frys entered their joint mark on 29 August 1822. Their work, which is not common, includes a pair of five-light candelabra, London, 1824/25, the bases of which are cast with the royal arms. It has been suggested that they might have been Elliott’s outworkers.

In 1842 Elliott apparently handed over the day to day running of the business to his son, Richard William. The latter’s mark, entered on 13 January that year, is seldom seen, however, which his hardly surprising because he was declared bankrupt less than two years later in November 1843.11 Meanwhile, his father, a widower, retired with his daughter12 to a five bedroom house at Northfleet Hill, near Gravesend, Kent, with ‘excellent soft water, commanding views of the river and country,’13 where he died in 1855. His will, signed on 12 March 1852, was proved on 17 September 1855 by his executors, his daughter and his nephew, John Julius Elliott (1821-1897).14

The following is a select list of items bearing William Elliott’s mark (sometimes erroneously attributed to the silver spoon and fork maker, William Eaton), which were or are believed to have been retailed by Thomas Hamlet:

1814 – a silver-gilt tankard, goat and putti pattern,15 engraved with the royal arms, said to have been from the collection of Frederick Augustus, Duke of York (1763-1827). (Christie’s, London, 25 March 1981, lot 151)

1818 – a pair of silver-gilt candlesticks, the stems in the form of young Chinese noblemen (Sotheby’s, London, 30 November 1967, lot 121)

1820 – a silver-gilt ewer and basin, engraved with the arms of Princess Augusta Sophia (1768-1840), second daughter of George III and Queen Charlotte. (Sotheby’s, New York, 6 April 1989, lot 93)

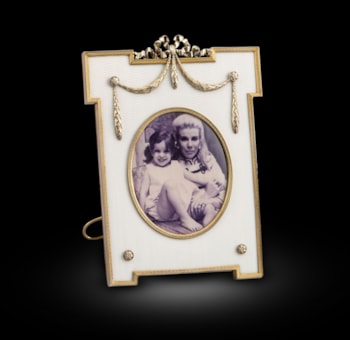

1820/25 – a silver-gilt toilet service, engraved with the initial M below a royal coronet for Princess Mary, later Duchess of Gloucester (1776-1857), fourth daughter of George III and Queen Charlotte. (Christie’s, London, 6 May 1959) Subsequently items from this service appeared at auction separately, including the mirror, 1825 (Sotheby’s, London, 14 December 1972, lot 63), and two caskets, 1820 (Sotheby Parke Bernet, New York, 14 February 1983, lot 46 and Sotheby’s, London, 2 June 1992, lot 126).

1821 – a silver coffee pot, stand and burner, engraved with the arms of Frederick Augustus, Duke of York (1763-1827). (Christie’s, London, 22 March 1827, 4th session, lot 82; Sotheby’s, London, 6 March 1997, lot 126)

1822 – a silver six-light candelabrum centrepiece, presented to the Duke of Buckingham and Chandos, the base stamped: ‘Hamlet, goldsmith to His Majesty The Duke of York & Royal Family’

1823 – a pair of silver wine bottles or flasks, engraved with the arms of Peel of Drayton Manor, Staffordshire (Christie’s, New York, 17 October 1996, lot 246).16 These are copies of the pair of flasks, George Garthorne, London, 1690, which were in the collection of Frederick Augustus, Duke of York (1763-1827) (Fig.3).17

1826 – a silver entrée dish and cover, engraved with the arms of George Hamilton Chichester, Earl of Belfast, later 3rd Marquess of Donegall (1797-1883), against whom in of before 1834 Thomas Hamlet had secured two bonds for the repayment of £23,059 and £11,251 13s.18

1829 – a pair of silver candlesticks, the stems cast as figures of Pluto and Prosperpina after original Kloster Veilsdorf porcelain candlesticks, the original model for which is thought to be by Friedrich Wilhelm Eugen Döll.19 (Christie’s, London,18 May 1966, lot 14)

1829 – a silver two-bottle inkstand with table bell, inscribed: ‘The Gift of his Majesty King William the 4th to Prince George of Cumberland 27th May 1832’ (Christie’s, 12 June 2007, lot 27)

1832 – a pair of silver seven-light candelabra, the bases stamped: ‘Hamlet Goldsmith to the King’ (Christie’s, London, 23 May 1973, lot 48)

You May Also Like