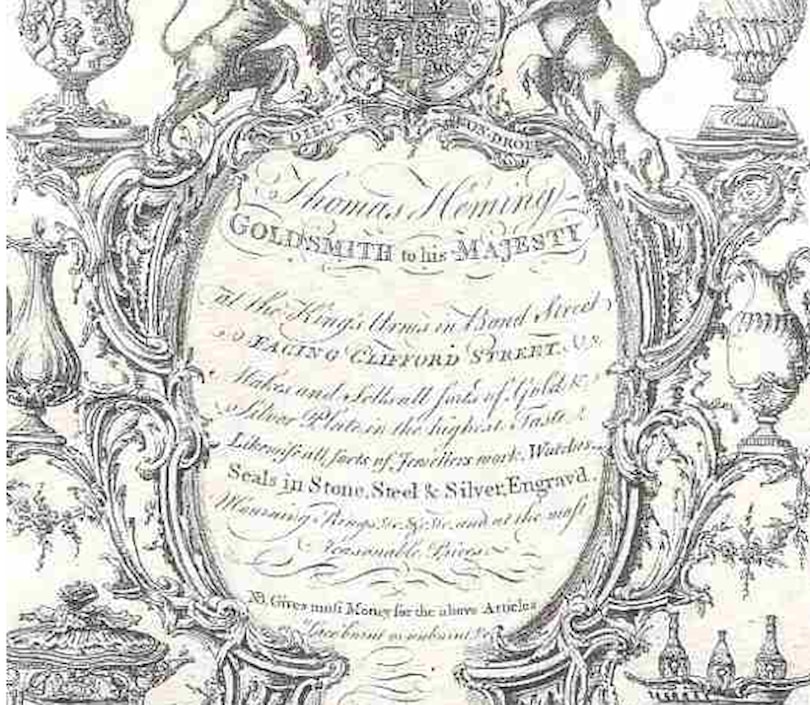

The overall form of Heming's bacchic cups and covers derive from French designs of the 1740s, most notably those of Pierre Germain (1720-1783), of which Heming was aware, as shown by his use of ewer and tureen forms on his trade card taken from the work of Jacques Roettiers and Edme-Pierre Balzac. The cups also show a more direct stylistic influence of the rococo works from the 1730s and early 1740s of goldsmiths such as Frederick Kandler (fl.1735-1778), Paul de Lamerie (1688-1751) and George Wickes. The bacchic putto finial can be found on a cup and cover in the Royal Collection, attributed to George Wickes and a similar finial features on a cup by de Lamerie in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum, New York dating from 1742, as cited by Hilary Young in his article 'Thomas Heming and the Tatton Cup' in The Burlington Magazine, vol. 125, no. 962, pp. 282-285. Young also suggests that the handles of the immense Jerningham Wine Cistern, now in the Armoury Museum, Moscow, modelled by the sculptor John Michael Rysbrack and executed in silver by Charles Kandler, may also have been influential, however, Heming would have only known the piece from contemporary engravings.

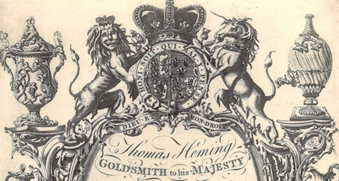

Heming produced a number of cups and covers with various combinations of bacchic elements. The largest cup of the present suite is very similar, with its Bacchante and Pan handles, to the cup depicted on the top left-hand corner of Heming's trade card. The cup on the trade card has the seated putto finial found on the pair of smaller cups. It has been suggested that they are some of the last works in the Rococo style, however, it could be argued that they are precursors to the later Rococo Revival style of the early 19th century. Hilary Young discussed the various related cups and their design influences in his article, op. cit., centred around a study of the unmarked Tatton Cup, in the Manchester City Art Gallery, now attributed to Heming, circa 1760. He lists the earlier comparative examples above and additional similar cups, such as that of 1759 with Bacchante and Pan handles and putto finial, in the Victoria and Albert Museum; its earlier companion, engraved with the same arms, was sold Christie's New York, 29 April 1987, lot 529.

A very similar cup in the collection of the Dukes of Devonshire at Chatsworth has an unmarked body, but the cover, with putto finial, is marked for Emick Romer, 1761. Young suggests that Heming may have subcontracted Romer to produce the cup and cover as he would have been fully committed in his role as Royal Goldsmith creating the coronation plate of King George III. Another example with Bacchante and Pan handles with a putto finial was in the collection of the Dukes of Cambridge and was sold Christie's, London, 6 June 1904, lot 92. The 3rd Earl of Bute, Heming's great patron and champion, commissioned a pair of similar cups, with serpent entwined handle, sold The Bute Collection, Christie's, London, 3 July 1996, lot 78.

Trade card of Thomas Heming. © British Museum Images

The design for these exceptional covered cups is so unique that it is listed among the most distinguished objects made by Thomas Heming and feature in his trade card, which dates to around 1760. The Heming cups are most likely influenced by a model produced by Jacques Roettiers and Edme-Pierre Balzac. Their rococo cup features a different and less richly decorated background as the example presented here.

To have been counted among the objects most representative of the craftsman’s work proves how well this design was received at the time of which this set of three stunning examples were completed. They also appear to be among the earliest recorded dating to 1752. Thomas Heming became royal silversmith to King George III in 1760.

These perfect examples of naturalism in silver are covered in vine tendrils, leaves, bunches of grapes, caterpillars and flies. Here Heming’s ‘musca depicta’ is not created with a brush but rather modelled first in wax, then cast and lastly hand chased to bring his three-dimensional interpretation of perfection to life.

Musca depicta ("painted fly" in Latin; plural: muscae depictae) is a depiction of a fly as a conspicuous element of various paintings. The feature was widespread in 15th- and 16th-century European paintings, and its presence has been subject to various interpretations by art historians. Many argue that the fly holds religious significance, carrying connotations of sin, corruption or mortality. There exist several anecdotes from the biographies of various artists who, as apprentices, allegedly painted a fly with such skill as to fool their teacher into believing it was real. Well-known examples are those about Giotto as an apprentice of Cimabue and Andrea Mantegna and his master Francesco Squarcione. These anecdotes were widespread and contributed to the humorous interpretation of the trompe-l'œil flies.

It is easy to envisage these ideas when on gazing upon these cups and covers.

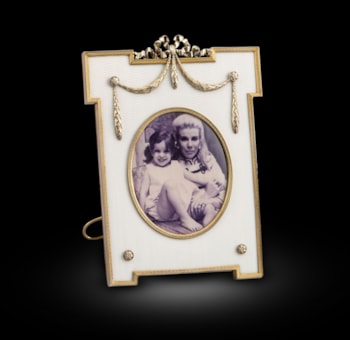

Mr and Mrs Sheldon Wilson; Sotheby's, New York, 16 October 1996, lot 303.

The son of a Midlands merchant, Thomas Heming was apprenticed to Edmund Bodington on March 7, 1738, and turned over on the same day to the Huguenot goldsmith Peter Archambo. He registered his first mark in June 1745; in 1760 he was appointed principal goldsmith to King George III, in which capacity he was responsible for supplying regalia and plate required for the coronation. Heming held this appointment until 1782, when he was ousted after an investigation into his apparently excessive charges. Grimwade (1976, p. 543) comments that "some of his earlier surviving pieces in the Royal collection show a French delicacy of taste and refinement of execution which is unquestionably inherited from his master Archambo." Among Heming's outstanding works are a silver-gilt toilet service made for Queen Caroline of Denmark in 1766 (Dankse Kunstidustrimuseum, Copenhagen; Hernmarck 1977, pl. 727) and a wine cistern of 1770, made for Speaker Brownlow (Belton House, Lincolnshire; Grimwade 1974, pl. 12).

You May Also Like