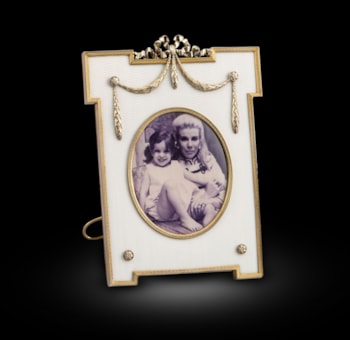

The heavy, extremely representative rectangular snuffbox with a slightly domed lid and baluster-shaped sides is decorated with hunting scenes in high-quality goldsmith's work, with the sides and base as well as the outer surface of the lid completely decorated with reliefs. The lower edge of the lid is decorated all around with a multiple wavy band pattern that rises in an arch at the centre front to form a thumb rest. The recessed foot section is decorated with a flat diamond frieze. Multiple curved cartouches of rocailles and C-arches frame the miniature hunting scenes on a finely chiselled, so-called sablé ground.

A wild boar hunt is depicted on the top of the lid, with the hunter striking down the animal with a deerstalker as it is brought down by a pack of hounds. In the background is an approaching hunter with a signal trumpet.

The outer side of the base shows a hunter with a dog whip pursuing a stag on horseback, which is being pursued by a hunting dog. A castle complex on a rugged rock can be recognized in the left background. The sides show the following depictions: a hunter with a shotgun sitting among his prey, stroking his faithful hunting dog; a beater trying to hold back his dog; a resting hunter with two dogs; a kneeling hunter with a rifle at the reacy, sitting in ambush with his two dogs.

Hunting as a courtly privilege

In the 17th and 18th centuries the hunt was both a courtly "sporting event" as well as an aristocratic celebration and represented a privilege of the nobility in a society structured according to rank and position. As a status symbol and self-confirmation of the nobility the hunt grew in importance with the spread of absolutism. For the lower nobility it was a way of clearly distinguishing themselves from non-aristocratic classes.

Under the influence of the Versailles court, at the end of the 17th century the parforce hunt, the chase of a single deer, was adopted by German courts, too. The considerable expenditure in terms of staff, horses and hounds made the hunt into a display of princely pleasures which had become a pure diversion. The actual work was carried out by the hunt staff who also led the hounds. The hunting party only

appeared when the quarry had been "fixed"; the master of the hunt then gave the exhausted, collapsed animal the coup-de-grace using a hunting knife.

Generally, the hunt was followed by a festive banquet, above all when important guests were present. For the members of the lower nobility in particular the events offered a welcome change and represented an improvement of their social position. Particularly in the wooded areas of Saxony and Württemberg that were rich in game hunting was widespread. However, this kind of chase had little in common with the classic stalking, as in the hunters' understanding the animal's chance of escaping was seen as a general criterion of the hunt. These dramas are recorded in contemporary reports, in paintings, drawings or porcelain pieces, in many cases graphically and with great precision.

Hunts served the ruler as a way of cultivating dynastic and diplomatic relations, as the expenditure on the guests combined with the extravagant celebrations stood for the reputation of the court. The erection of hunting lodges in wooded areas that had plenty of game made life more comfortable for hunt guests and became a question of prestige in the rivalry as to who could offer greater lavishness. The Jagerhof in Dresden with its rich holdings soon became a centre point of the sport of hunting. Hunters were sent to Dresden from all around the world and foreign rulers regarded it as an honour to enrich the collection through gifts of valuable weapons or rare animals. For numerous members of the nobility the hunt became their sole pleasure and determined the rhythm of their lives.

Gold snuffboxes as aristocratic gifts

Gold snuffboxes played a particularly important role as diplomatic gifts and were revered by high-ranking personalities of rank in much the same way as precious jewellery.

Elaborately crafted gold snuffboxes, sometimes with additional gemstones, were among the favoured gifts for exchanges between two princes or farewell gifts to departing diplomatic representatives.

The Russian Tsarina Catherine I (1729-1796), for example, was very fond of giving snuffboxes to envoys. With these miniature works of art, potentates were able to discreetly demonstrate their personal esteem without the recipient appearing to be bribed - even if the precious object was later resold or even sold back to the manufacturer. For example, the imperial electoral commissioners usually received a precious gold snuffbox as a private gift from the newly elected prince-bishop at the farewell audience. Such boxes were also used in cases where a seemingly profane gift of money was to be avoided if possible - for example as an expression of thanks and gratitude to courtiers or doctors, as well as fine artists or actors.

French princesses always had many elaborate snuffboxes in their "corbeilles de mariage" presented by the royal court, most of which the bride gave away to her entourage and wedding guests, while she only kept a few particularly precious examples herself.

The goldsmith Otto Christian Sahler

The double signature "Sahler" refers to Otto Christian Sahler (Augsburg 1722/27 - 1810/11 Berlin), who came from a famous Augsburg family of goldsmiths. He completed an apprenticeship with a silver worker and began modelling at an early age. He settled in Dresden in 1752 and modelled numerous portraits and other depictions in wax, but also continued to create important works in silver. Sahler also worked as an engraver, imitating chalk drawings and using the hammer technique in the manner of Jan Lutma (c. 1584-1669).

In 1770 he went to Berlin, where he taught as a drawing master at the Grey Monastery. He embossed members of the Prussian royal family and the Russian tsars in wax, and painted pastel portraits and landscapes in watercolour. From 1783 or 1784 until his retirement in 1800, he taught the third drawing class at the Berlin Academy of Art, where he regularly presented works at the academy exhibitions from 1786 onwards (2).

Templates and comparative pieces

Stylistically, Otto Christian Sahler orientated himself on the rich pool of hunting engravings by the Augsburg animal painter, engraver, and publisher Johann Elias Ridinger

(1698-1767). Two of Sahler's depictions on the snuffbox to be presented are direct quotations from the engraving "Die Schweins Hatz". An equestrian figure and the fleeing stag are also borrowed from Ridinger's oeuvre.

Only a few snuffboxes with Sahler's signature have survived, although one oval example, worked entirely in gold, dates from his Berlin period and depicts scenes from the Seven Years' War. Two further boxes combined with lapis lazuli and amethyst, the latter of which also belongs to the hunting genre, were auctioned at Sotheby's in 2005 and 2014. In addition, a no longer available "Fassung einer Steindose. London, Georg Bonnor. Ausgestellt 1877 im Victoria u. Albert-Museum, London"(3) is mentioned several times in the literature.

The present snuffbox can therefore be considered an outstanding work from Otto Christian Sahler's early creative period, which is unrivalled in terms of its outstanding craftsmanship, both in design and execution.

Ref 2 "Cf. Sahler, Otto Christian", in: G. K. Nagler, Neues allgemeines Künstler-Lexicon oder Nachrichten von dem Leben und den Werken der Maler [..), Munich, 1845, vol. 14, p. 195.

Ref 3 "Mount of a stone box. London, Georg Bonnor. Exhibited 1877 in the Victoria and Albert Museum, London" (Marc Rosenberg, Der Goldschmiede Merkzeichen, 2d edition, Frankfurt/Main, 1911, p. 210, no. 690 and Wolfgang Scheffler, Berliner Goldschmiede. Daten Werk Zeichen, Berlin, 1968, p. 221, no. 1119.

South German private collection (since c. 1900)

For comparison:

Christie's Geneva, 11th May 1989, published in: Abraham Kenneth Snowman, Eighteenth Century Gold Boxes of Europe, Woodbridge, 1990, p. 341, pl. 717, fig. 5

Formerly Prince Demidoff collection, Sotheby's London, 29th November 2005, lot 45, fig. 6

Formerly Simon Harcourt, 1st Earl Harcourt (1714-1777), Sotheby's London, 6th November 2014, lot 87, fig. 7

Lorenz Seelig, Golddosen des 18. Jahrhunderts aus dem Besitz der Fürsten von Thurn und Taxis. Die Sammlung des Bayerischen Nationalmuseums im Thurn und Taxis-Museum Regensburg, Munich, 2007

Heiner Borggrefe ed. al. (eds.), Hofjagd. Privileg und Spektakel, exh. cat. Weser-renaissance-Museum Schloss Brake Lemgo, Paderborn, 2021

For objects made of gold and imported from countries without a trade agreement with France since 1893.

You May Also Like