George Wickes’s Gentleman’s Ledger records these candelabra as having been delivered to the Earl of Kildare on 27 May 1745: ‘fine chais’d candlesticks & branches & false nozils,’ 308oz. 12dwt. at a cost of the silver (£95 3s. 6d.) and fashioning (10s. per oz.), totalling £154.

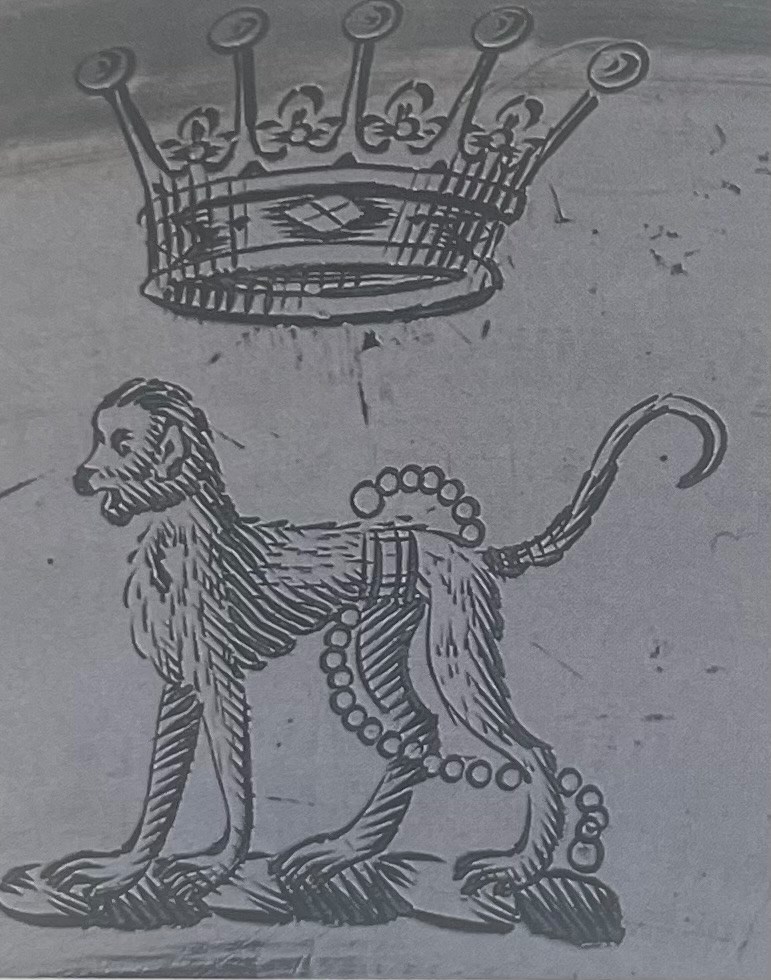

The crest is that of James (29 May 1722 – 19 November 1773), son of Robert FitzGerald, 19th Earl of Kildare and his wife, Mary, daughter of William O’Brien, 3rd Earl of Inchiquin. Styled Lord Offaly, he succeeded as 20th Earl of Kildare upon the death of his father on 20th February 1744 aged just twenty-three. He was created a peer of Great Britain as Viscount Leinster of Taplow in 1747, advanced to the Earldom Offlay and the Marquessate of Kildare in 1761, and the Dukedom of Leinster in 1766. He was married on 7 February 1747 to Emily (d.1814), daughter of Charles, 2nd Duke of Richmond and Lennox, by whom he had nine sons and ten daughters. The Earl was created Marquess of Kildare in 1761 and in 1766 Duke of Leinster. He died at Leinster House, Dublin.

The design for the current candelabra made its way to England from France with remarkable speed after its inception. Appreciation for French styles and tastes was well developed in London in the first half of the 18th century, and many of Wickes' clients would have been demanding versions of the strongly rococo pieces they had seen on their travels. It was in Meisonnier's 1734 publication that we see the origins of these candelabra; described as Chandeliers de Sculpture en Argent the stem spirals with such fluidity that it seems an impossibility for such a creation to be made in a rigid material like silver, and the branches spring from the stem with effortless vibrancy. The whole is nothing less than a masterpiece of daring and inventiveness. The design must have proved a popular one because it was adopted and adapted by the great master orfèvre Thomas Germain soon afterwards in his most famous creation of the candelabra.

How exactly Germain's model journeyed over the Channel is not known. One possible theory is that this pair were produced in Paris in the workshops of Germain and delivered in London to be hallmarked by George Wickes.

More likely, Wickes’ ledgers are explained by the skilled work required in casting – presumably from one of Germain’s originals and the finishing of the figures. This would account for the unusually high charge made for “making”, at 10s per ounce.

Wickes was one of the two silversmiths known to have left their marks on versions in 1744/45: This pair of by Wickes and a second pair with the mark of John Hugh Le Sage. With premises a stone's throw away from one another, it seems very likely that there would have been collaboration between Le Sage and Wickes. The designs, or perhaps even the casting moulds for the current lot must have been kept safe because Parker & Wakelin (Wickes' successors) made use of them for a pair in 1770, now in the Fairhaven Collection at Anglesey Abbey. A further pair was supplied by Paul Storr for Rundell, Bridge & Rundell in 1816 for the Duke of Leeds and a similar centrepiece 1825 with the maker’s mark of John Bridge.

Robert Garrard’s firm used the base for several candelabra during the 1820’s but replaced the fauns with male and female figures closely based on figural candlesticks made in the Parisian court goldsmith Etienne de Launay for Louis XIV at Versailles.

James FitzGerald wasted little time in imposing his taste on his ancestral home: Carton House in County Kildare, Ireland. The dining room ceiling was said to be the finest in Ireland, and the Earl had brought in the services of two Italian stuccatori to apply the finishing touches. If the current candelabra had been ordered for this room at Carton, they could not have enjoyed a much finer or appropriate setting. Equally, the Earl might have had in mind Kildare House, on the outskirts of Dublin, as the home for his new candelabra. Weight is added to this theory by the fact that building work started in 1745, most likely the year Wickes delivered his commission. Of course, the idea of silver remaining in one property is a modern one, and it is quite probable that the Earl took his candelabra and his celebrated Leinster Service (also supplied by Wickes) with him to wherever he was staying and entertaining.

The Masterpiece of Thomas Germain

So famous was the workmanship of silversmith Thomas Germain in eighteenth-century France that the philosopher Voltaire immortalized his "divine hand" in a poem. Although Germain came from a family of silversmiths, he first studied painting. While still young he went to Rome, where he was apprenticed to a goldsmith. On his return to France, Germain was received into the guild as a master silversmith; three years later, in 1723, he was granted apartments in the Palais du Louvre and appointed as orfèvre du roi (silversmith to the king).

From then until the end of his life, Germain was employed in making silver and gold objects for Louis XV and the French royal family. Inventories show that Germain supplied the royal family with a few pieces every month: gold mustard pots, silver candlesticks, chamber pots, plates, and dishes. Every time a prince or princess was born, Germain made the child's rattle. He did not work exclusively for Louis XV but also produced toilette and dinner services for the king of Portugal, the princesses of Brazil, and the queen of Spain. On Germain's death in 1748, the king of France ordered a requiem mass to be sung for him.

These George Wickes candelabra are identical to examples made in the workshop of the French Royal Goldsmith Thomas Germain. The model was evidently a popular one for Germain and a source of pride for him. Following the revolutions and upheavals in France, only a handful of examples with Germain’s mark are known to have survived, all of them outside France. Two pairs were supplied by him to the Portuguese court and another pair, with Paris hallmarks for 1732-3, is now at the Detroit institute of Arts. The latter pair was commissioned by an English patron, Sir Lionel Tollemache, for his house in Richmond. Two pairs bearing the mark of Germain’s son François-Thomas are also known.

These candelabra with satyr figures are among the best creations of eighteenth-century French silver ever to be made. This seems to be the view shared by their author, the great Thomas Germain himself, for in the celebrated portrait of him and his wife painted in 1736 by Nicolas de Largillière, the goldsmith proudly acknowledges the model of one of these masterpieces.

The present candelabra have a movement together and lightness, which were to become the overriding themes of the rococo in the 1730s. They are typical of a tantalizing small group of work surviving silver from the workshop of the elder Germain, of whom Léonor d’Orey has commented, “He was able to marry fantasy and equilibrium, extravagance, and solidity, restraining the most unbridled excesses of rococo with a strict internal logic of a powerfully architectural nature.

It is fitting that the branches of these candelabra, formed as sunflowers emblematic of the sun god, Apollo, should support the candles. The sunflower was the symbol of Chlyte, who according to Ovid’s Metamorphoses, was loved by Apollo and transformed into a sunflower, forever turning her head to follow the path of her lover, represented here by the light shed by the candles. The male and female satyrs hold aloft garlands of oak leaves, emblematic of hospitality, but the true theme of these candelabra is Arcadian love. Thomas Germain, pointing to the model of one candelabrum in his portrait, is also pointing to his love for his wife, shown seated at his elbow.

Thomas Germain and his wife

By Nicolas de Largillière (1656-1746), 1736.

Museum Calouste Gulbenkian Lisbon

More than two and a half centuries have passed since Meissonnier's famous candlestick design - drawn from three angles and aptly described as "Chandeliers de Sculpture en Argent" - was published in Paris.(1) His contemporary, the great master orfèvre Thomas Germain, was quick to realize the appeal of spiralling, sensuous figures to a clientele with a growing taste for the rococo, or le genre pittoresque as it was it known in France, and his version, fashioned in 1734, in which satyrs replaced the putti of Meissonnier, was widely acclaimed. His pride in this particular piece is apparent from Nicolas de Largillière's portrait of 1736. (2) Germain's design soon found its way to England. Living as we do in an age of sophisticated transport; we forget that the educated classes in the eighteenth century were intrepid voyagers. It is clear from the journals of the period that they were very well informed on matters of aesthetics and their libraries were enriched with books of designs collected on their travels. The more avant-garde of the goldsmiths' clients visited continental ateliers and would have returned to England lauding the latest masterpieces, including, no doubt, Germain's candelabra based on the design of the incomparable Meissonnier. Dependent as ever on the French in matters of fashion, the English goldsmiths would have been avid to acquire information on the new style. The Huguenot goldsmiths working in England were instinctively attuned to all things French and their traditional casting techniques lent themselves to the exigencies of the new fashion. Surprisingly such innovators as de Lamerie and Crespin appear to have made no attempt to produce candelabra after the Germain model, possibly for lack of clients with avant-garde tastes. It fell instead to Charles Frederick Kandler who fashioned in 1738: candelabrum which, whilst clearly inspired by Germain's design, was not an exact copy. Kandler has replaced Germain's Arcadian serenity with human figures that are both visually exciting and intellectually stimulating. His version (3) has been imaginatively linked to the Greek myth in which Deianira gives Heracles a scarf dipped in the blood of the centaur Nessus. Lacking perhaps the elegant balance of Germain, Kandler's candelabrum is remarkable for its fluid modelling and superb workmanship.

At about the same time, strangely enough, his namesake, J.J. Kändler, chief modeler at the Meissen Porcelain Factory, was clearly influenced by Meissonnier when he produced the candelabra for his famous Swan Service.

Six years passed before Germain's design was emulated in London and then two goldsmiths were involved: John Hugh Le Sage and George Wickes. In 1744 Le Sage at the sign of The Golden Cup in Suffolk Street, Haymarket, produced a faithful copy' engraved with the arms of George II. The candelabra were presumably intended for ambassadorial use or as a present from the monarch since they are not listed in the inventories of royal silver. In the same assay year George Wickes, two streets away at the sign of The King's Arms & Feathers in Panton Street, Haymarket, made another pair for his client the Earl of Kildare. Given the small circle in which they lived and worked, it is inconceivable that Wickes and Le Sage were unaware that each had been entrusted with prestigious order involving a design by the important Thomas Germain. Meissonnier and Germain were sufficiently well known even after their deaths for their names to figure in a satirical print published in London in in 1759 entitled "The French King in a Sweat or the Paris Coiners" (5): to Wickes and his fellow goldsmiths they would have been household names in the 1730s.

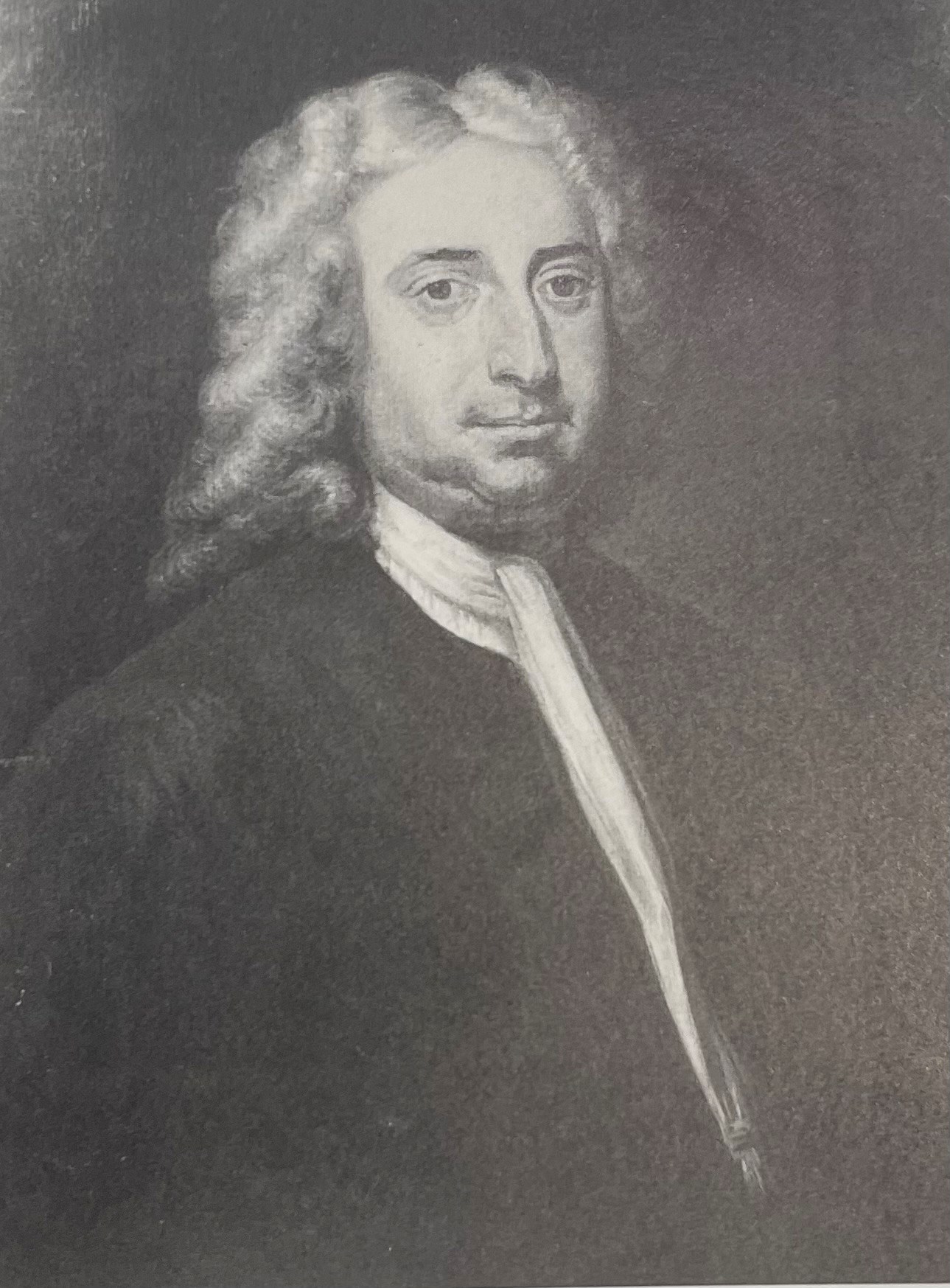

Wickes's client, the Earl of Kildare, would certainly have been acquainted with the oeuvre of Meissonnier and Germain. He had spent over two years between 1737 and in 1739 in making the grand tour and although he was only seventeen on his return he seems to have acquired: very real feeling for le genre pittoresque. Five years later, in 1744, he became, on the death of his father, 20th Earl of Kildare and he set about giving full rein to his rococo tastes. This accomplished young man soon made an impression at Court. At a Drawing Room described by the Reverend William Harris he appears to have outshone the Prince of Wales and the Duke of Cumberland. The cleric noted that "Lord Kildare was unquestionably the finest of any gentleman there," attired in light blue silk coat embroidered all over with gold and silver "in very curious manner," (6) A portrait of him in more sober garb by Sir Joshua Reynolds suggests that he was pleasant looking rather than handsome: there is not a hint of the languid aesthete. Ireland was his natural habitat, and he devoted much time, zeal and money on the refurbishing of Carton, his ancestral home. Richard Castle was the architect responsible for the many alterations and additions. The dining-room ceiling, finished by the Italian stuccatori Paulo and Filippo Francini, alone cost £501 and was said to be the finest in Ireland. The total cost of the work at Carton exceeded £21,000.

Apart from Carton, the Kildare owned a large timber-framed old-fashioned edifice in Dublin which was not at all to the taste of the new earl. He decided to replace it and called once more on the services of Richard Castle. The new Kildare House (renamed, after the dukedom, Leinster House), was built in Molesworth Fields on the outskirts of Dublin. It is best described in the words of Brian Fitzgerald, great grandson of the 3rd Duke of Leinster: "The upper windows commanded fine views of Dublin Bay. The grandeur of the exterior was equalled only by the magnificence of the interior." It was possibly with this great mansion in mind building began in 1745 - that Kildare ordered from George Wickes the pair of candelabra after Thomas Germain's design that form part of this sale.

It is perhaps pertinent at this point to speculate on the respective delivery dates of the candelabra by Le Sage and Wickes. There is unfortunately no documentary evidence for those of Le Sage, but in Wickes's Gentlemen's [Clients'] Ledgers there is incontrovertible proof that Kildare's candelabra were delivered on May 27, 1745. The date letter was changed at the Assay Office in Goldsmiths' Hall on May 29. Whilst the pieces bear the letter for the year 1744, some months would have gone into the manufacture of the order, and it is reasonable to suppose that the work would have started early in 1745

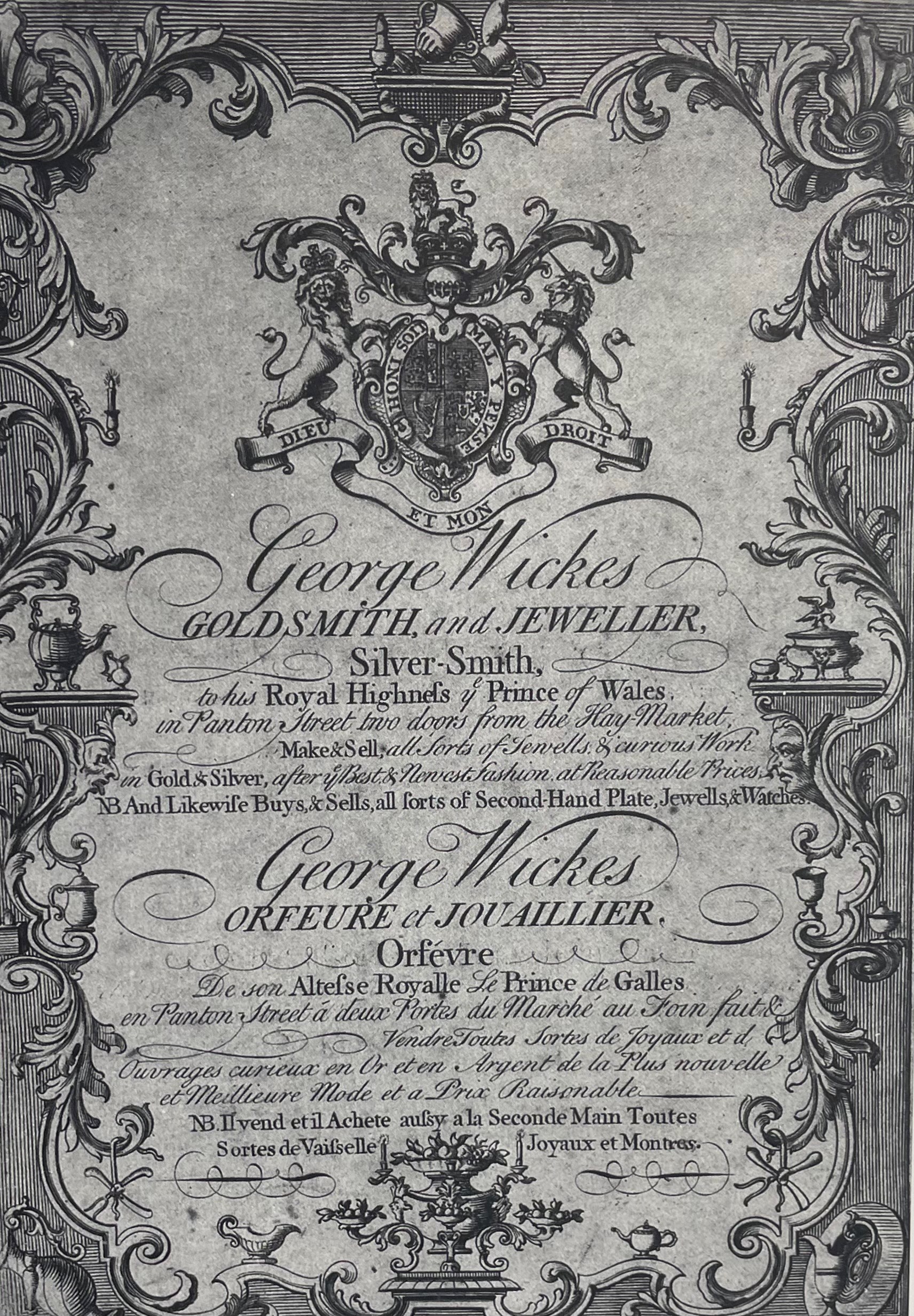

On Lady Day (March 25) 1744 Wickes made a significant move. He acquired a second house next door but one in Panton Street and moved his workshop there from the first house which he then used purely as a shop and dwelling place. The Kildare candelabra would have been made in the new premises. In June 1735 in an advertisement in the London Evening Post he had emphasized his role "as the maker" and he no doubt continued to play a major part in the actual manufacture until Edward Wakelin, formerly Le Sage's senior journeyman, joined him in November 1747.

Trade-card of George Wickes in Panton Street circa 1735.

(Courtesy: Garrard & Co. Ltd., London)

It is obvious from his output as recorded in his ledgers that he would have been physically incapable of making all the objects himself and it is an established fact that from time to time he sub-contracted specialist work and even important orders to fellow goldsmiths. This practice could well in have worked in reverse and he in his turn in may have undertaken work for others though no to records survive to prove this possibility. The obsession with makers' marks dates from comparatively recent times and would no doubt have surprised and possibly amused the likes of Wickes and Le Sage.

"A book of drawing"

There is no way of knowing why Lord Kildare chose Germain's design in 1744. If Le Sage's version preceded that of Wickes the Earl may well have seen it and, with his predilection for the rococo, gone post-haste to Wickes to order a copy. He may, on the other hand, have felt the need of a pair of fashionable candelabra at Carton and given a great deal of thought to the form it should take, or had long harboured a desire to own silver wrought to the design of Thomas Germain and needed only his succession to the earldom to provide the impetus. It says much for his upbringing and education that this young man of twenty-three should have been so well versed in French culture and possessed of such an assured taste. There is a hint of a clue in the Kildare account. Wickes's ledgers seldom shed light on design sources and his syntax on occasion is infuriatingly and tantalizingly vague. For what it is worth the entry reads as follows: "To cash pd. for a book of drawing [sic] & binding... 18s. 6d." This could refer to a book of silver designs or the binding into book form of loose plates of designs, but that can only be conjecture. The "book of drawing" might have had no connection with wrought silver and Wickes might merely have obligingly undertaken to get some old views of Dublin Bay rebound for his client: but at some not-too-distant date a book with Kildare bookplate may surface and Germain's designs again see the light of day.

Wickes's familiarity with full-blown rococo designs was long established. Already in 1735, barely year after their publication in Paris, he was happily borrowing motifs from Jacques de la Joue for the Bristol Ewer and Basin.(7) The body of the ewer - a graceful pear shape unknown even in the oeuvre of Paul de Lamerie at this time - is decorated with a male mask which appears to have been taken from a print after Gaetano Brunetti which must predate the edition of his suite issued in 1736. Wickes's use of the motifs of de la Joue and Brunetti is the earliest evidence of the importation of genre pittoresque prints. Whilst delighting no doubt in the obtaining of such a prestigious order as the Kildare candelabra, Wickes is unlikely to have been overawed by the technical challenge of Germain's rococo fantasy. None of Wickes's working drawings has survived, nor is there any trace of the eighteenth century equivalent of the modern worksheet. It is hardly likely that he would have made the candelabra from scratch - his workshop not withstanding if John Le Sage's work was already well advanced and all the necessary models and moulds in his atelier available either to borrow or hire. Le Sage if indeed he was the precursor - would himself have employed specialist modelers and chasers for such important work. These skilled craftsmen were the true artists of orfevrerie: they go unsung for lack of signed work and documentation.

The modellers were close at hand. A short walk from the Haymarket brings one still to St. Martin's Lane. It was here that the St. Martin's Academy was founded by William Hogarth. Its principal purpose was the teaching of life drawing, but the instruction provided would seem to have been far more broadly based judging by the varied skills of its teachers, who included Gravelot, Moser, Roubiliac and Yeo, all of whom would have had professional links with metalworkers. The tutors and their pupils frequented Slaughter's Coffee House in St. Martin's Lane, cosmopolitan and convivial group with a lively interest in art and design. (8) On these skilled artist/craftsmen the goldsmiths depended when their work involved modelling of a high order. If Wickes's early Workmen's Ledgers had survived to supplement his other account books in the Victoria & Albert Museum modeler and chaser (who may have been one and the same man) the names of the employed on the Kildare candelabra would be revealed, together with those of the goldsmiths to whom he sub-contracted work from time to time.

The ledger entry for the Kildare candelabra is brief and business-like. Two "fine chais'd candlesticks & branches & false nozils" appear against the date May 27, 1745. The Troy weight is given as 308 ozs. 13 dwts. The prime cost was £95 3s. 6d. which works out at approximately 6s. 5½d. per oz. To this figure was added a making or fashioning charge of 10s. per oz. Some idea of the expense involved in the interpretation of Germain's design can be gained by comparing these figures with Wickes's charges for the magnificent William Kent horse-head tureens made for Lord Montfort in 1744 (9): here the basic cost was 6s. 2d. per oz. and the making charge 7s. 6d. per oz. There is no mention of the designer in either account, nor is there any clue to the identity of the craftsmen responsible for the models and "fine chaising."

A possible candidate for the modelling is the sculptor Michael Rysbrack whose wax figures were used by Charles Frederick Kandler for his great cistern of 1734. (10) George Michael Moser is, however, a far more serious contender on the strength of his authorship of a swirling rococo design for a female caryatid candlestick: circa 1740, the drawing, signed "G.M. Moser iv. & delt," is in the Victoria & Albert Museum. (11) The Museum has also acquired two pairs of candlesticks based on this design. (12) They are, unfortunately, unmarked and they lack the spiralling fluidity of Moser's design: informed opinion doubts his involvement in either the modelling or the chasing. Moser's versatility is illustrated by an anecdote recounted in Nollekens & his Times by W.T. Smith (whose father was Roubiliac's assistant). He relates a conversation between one Panny Betew (alias Pantin Buteux), (13) a minor Huguenot silversmith and something of a character, and Nollekens in which the latter speaks of "Mr. Moser, who was keeper of our [Royal] Academy... a chaser originally" as being one of "some clever men who modelled [sic] for the Bow concern."

Nicholas Sprimont and Chelsea

This mention of Bow is a timely reminder of the link between silver and porcelain. The year 1745 marked the start of serious porcelain production in Chelsea. Soon after, the Liègois goldsmith Nicholas Sprimont, following a brilliant debut in London with his Marine service for Frederick Louis, Prince of Wales, in the early 1740s, became involved with the Chelsea Manufactory, forsaking silver for porcelain. Sprimont was brought up with the Liègois fountain sculptures of Faydherbe, van Bossuit and Grupello and their influence can be seen in the rocaille detail and incomparable modelling of the male and female figures (14) poised momentarily on the prows of the boat-cum-shell sauceboats in the Prince's Marine Service (in the Collection of H.M. the Queen). Each sinuous body is supported by one hand which rests on the brim of the sauceboat, a pose very reminiscent of the figures on the Kildare candelabra. The man who modelled the triton and nereid on the Marine Service would have had no difficulty with Germain's satyrs. Although George Wickes was by appointment goldsmith to the Prince of Wales, there is no mention of Sprimont's jeux d'esprit in the royal account in Wickes's ledgers. Frederick may have delegated the transaction to the Earl of Baltimore, his Gentleman of the Bedchamber and also one of Henry and Robert Janssen's brothers-in-law, whose receipt book (15) in the Maryland Historical Society's archives reveals a payment of £149 to Nicholas Sprimont in January 1744.

Sir Joshua Reynolds, P.R.R (1723-1792)

James, 1st Duke of Leinster and 20th Earl of Kildare

Private Collection, photograph Courtauld Institute of Art

Crest of James FitzGerald,

20th Earl of Kildare, engraved on the candelabra bases

The entry unfortunately lacks the details Wickes might have provided in his ledger had the pieces passed through his hands. Research on Sprimont's early years in London has always been bedevilled by lack of documentary evidence. There is proof of his marriage at the age of twenty-six to Ann Protin at Knightsbridge Chapel, London, in November 1742, and of his entering a mark at Goldsmiths' Hall the following January, giving as his address Compton Street, Soho (close to de Lamerie and Wickes). The rate books show him in residence there until 1748, though he must by then have moved to Chelsea in whose rate books he appears in 1747. He is known to have stood godfather to Roubiliac's daughter Sophie in 1744 which suggests an intimacy with the sculptor which no doubt extended to his circle of artists, designers, modelers and chasers. Roubiliac himself produced models in his time, including the bronze figures decorating a musical clock later acquired by Augusta, Princess of Wales (16) Artists in the 1740s were not nearly as hidebound as they are today in our highly specialized times. The artists turned their hands to designing and the sculptors to modelling and it mattered little whether the object was of marble or metal. While Sprimont may have made a name for himself in Liège, no such reputation seems to have preceded his arrival in London. Until he could find his feet and register a maker's mark, he needed to make a living and his modelling gifts may well have stood him in good stead.

Lord Kildare's Commission

The models and moulds for the Germain candelabra must have been carefully stored. Wickes's successors, John Parker and Edward Wakelin, used them again in 1770 to make a further pair which is now in the Fairhaven Collection at Anglesey Abbey. The next known copy, fashioned under Paul Storr's direction at Rundell, Bridge & Rundell in 1816 for the Duke of Leeds and differing slightly from Wickes's version.

George Wickes was also the creator of the great dinner service made for Kildare between 1745 and 1747. It is very rare that such a service survives virtually intact. Known as the Leinster Service, (17) it takes its name from the dukedom created for Kildare by George III in November 1766.

Kildare's commissions would have been placed with a view to the grand scale entertaining expected of him as the first peer in Ireland. At the same time, he was giving serious thought to matrimony. That inveterate gossip Horace Walpole commented on his interest in Lady Emily Lennox, daughter of the Duke of Richmond, in a letter to Sir Horace Mann in Florence in April 1746, (18) but the sharp-eyed Mrs. Delaney had already mentioned it to a correspondent in July 1745 when Emily Lennox was still two months short of her fourteenth birthday. Emily Lennox and James Fitzgerald were married on February 7, 1747, when the bride was fifteen years and four months old. She was beautiful, loving and high-spirited and the marriage was a very happy one: in the course of its twenty-seven years, she bore Kildare nineteen children.

Her many pregnancies must have complicated Lady Kildare's life as a great hostess. Her butlers at Carton and Leinster House would have been responsible for the plate, but it would be interesting to know if the candelabra and the Leinster Service were trundled between the two great houses as occasion demanded. Seated at the long table under the lovely ceiling at Carton, the Kildare’s' guests could hardly be unimpressed by the fine silver. Was the Germain design talking point and did any of them privately think that the four pairs of candlesticks in the Leinster Service were somewhat pedestrian in comparison? There may have been among them connoisseurs who had actually seen the candelabra made by Germain himself, either in Paris or Lisbon, who could look detachedly at Wickes's work and evaluate it. One wonders how the cognoscenti would have reacted had they had the opportunity afforded us today of seeing the work of both masters side by side. Some would perhaps prefer Germain’s plainer socket and more naturalistic fruit clusters whilst appreciating the elegance of Wickes's basket-work bases uncluttered by heavy armorials. Could they in all truth look at these magnificent works of art without laughing to scorn the Abbé Le Blanc with his infamous strictures against the rococo in his Lettres d'un Français(19) in 1745 and his chauvinistic averment that London goldsmiths were mere craftsmen, whereas in Paris Meissonnier and Germain were designers and sculptors?

Edward FitzGerald, 7th Duke of Leinster, and by descent

Christie’s, London, 12 May 1926, lot 162 (Property of His Grace the Duke of Leinster)

Lionel Crichton of Crichton Brothers, London

Thomas Lumley, London

S.J. Phillips, London

Mrs. Ortiz Linares (1900-1980) (purchased 5 June 1951)

Thence by descent to her son George Ortiz (1927-2013)

Sotheby's, New York, 13 November 1996, lot 8

Koopman Rare Art, London

Elaine Barr, George Wickes, Royal Goldsmith, 1698-1761, London, 1980, pp. 84-86

Christopher Hartop, The Huguenot Legacy from the Alan & Simone Hartman Collection, pp126-131

Son of James Wickes late of St.Edmondsbury in the county of Suffolk upholsterer deceased, apprenticed to Samuel Wastell 2 December 1712 on payment of £30 (he signs Wicks). Free, 16 June 1720. Two marks (Sterling and New Standard) entered as largeworker, 3 February 1722. Address: Threadneedle Street. Third mark, 30 June 1735. Address: Panton Street, Haymarket. Livery, March 1739/40. Fourth Mark, 6 July 1739. Address: ‘at the King’s Arms, Panton Street near the Haymarket.’ More, however, is known of his working life than revealed in his mark entries. Heal records him as a plateworker, Leadenhall Street, before 1721, when he was presumable still working with Wastell, who was there at least 1705-8 (Heal). By c. 1730 he was in partnership with John Craig (see Ann Craig) at the corner of Norris Street, Haymarket, almost opposite his final situation. There is no recorded mark for this partnership, but a supporting fact to its existence is the apprenticeship to Wickes in 1731 of David Craig. Heal records the death of John Craig in 1735 or 1736, the former year that in which Wickes entered his Panton Street marks and it is clear from the surviving ledger (Messrs Garrard’s) that this is when Wickes began a really independent existence. The Panton Street mark was entered on 30 June and the ledger’s first entry is dated the 23rd of the same month. One folio (31) of the ledger is headed ‘My House’ and under 24 June appears the entry ‘To the King’s Arms and Feathers £14.3.6’, providing a terminus a quo for the Wickes appointment to Frederick, Prince of Wales, who was later to cause him considerable trouble. Heal records him as King’s Arms, Panton Street, two doors from Haymarket, 1735-61; and in partnership with Samuel Netherton as goldsmiths and jewellers, at the same address, 1751, left off business 1759. There is no mark for this partnership, and as will be seen below, it would seem as though Wickes renounced the silversmith’s side of the business to Edward Wakelin (q.v.) in 1747 and remained a sleeping partner with Netherton attending to the jewellery side. With the growth of the business by this time, as witnessed by the list of distinguished clients in the ledgers, there must have been of necessity a division of responsibility. The first ledger, which runs from 1735 to 1741, contains, among others, accounts for the Dukes of Devonshire and Chandos, Dowager Duchess of Norfolk, Marquess of Caernarvon, Earl Inchiquin and many ‘Lords’. In the next volume he added the Dukes of Kingston, Roxburgh, Montrose and Bridgwater, the Earls of Scarborough, Kildare and others, Admiral Vernon and Arthur Onslow, the Speaker. Bishops appear from time to time to add dignity to the list.

The account of Frederick, Prince of Wales commences on 24 March 1735/6 with a tactful gesture, ‘To a Black Eboney Handle for a tea kettle and a Button for a teapot os.od.’ The next entries set a more realistic standard ‘May 1. To a fine cup & cover 124 oz 17 d. £80. To a fine Bread Baskett 87 oz 9 d. £50’. There are several entries for the hire of plate for parties in November, December, January and August, the last ‘To the use of Plate for ye Oxford & Cambridge entertainment £6.6.0’. Frederick had been living at an extravagant rate and in September 1737 he was banished by George II to cool his heels at Kew and made attempts to retrench. ‘The Prince reduced the number of his inferior servants which made many enemies among the lower sort of people and did not save him money. He put off all his horses too that were not absolutely necessary and farmed all his tables, even that of the Princess and himself.’ (i.e. contracted his catering) (Hervey’s Memoirs). The blow fell, too, on Wickes who entered in his ledger: ‘ September 20 To the Damadge and Loss to me in a Large Parcell of Plate Bespoke and ordered by the Prince which was in such forwardness when counterdemand(ed) as amounts to more than £500.’ Later Wickes allows in credit ‘Sold Six Dozen of Plates and twelve Dishes at 6d per oz 2000 oz. £50’, obviously the charge for the plate tax, which he seems already to have charged his royal client. Then he cooled off and added ‘The Damadge on the other side (i.e. debit account) being Reduced by executing part of the work intended and I have now taken of token of the whole Damadge altho’ I have not Recd it any other wise than by the profit of the work made…£450’, thus writing off the matter. However, by February 1738 he had a new order from the Prince for ’18 chased Sconces weighing 426 oz at 5/11 per oz. £126.1.6 plus £5.5. for making each’, and from here the royal account returned to a satisfactory conduct. The most important piece recognizable in the account is the silver-gilt epergne designed by William Kent, and still, though added to by Rundell and Bridge, in the Royal Collection: ‘Nov.11.1745 To a silver gilt Epergne, a Table, 4 Saucers, 4 Casters, 8 Branch lights and Pegs 845 oz.9d. at 15/8 per oz £662.5.4 To Graving the Table 4 Saucers and Casters £23.16.0. To 6 Glass Saucers £3.3.0 To 2 Wainscot Cases £6.10.0.’ After the Prince’s death Wickes continued to work for his widow and in 1759 a modest account starts for ‘Their Royal Highnesses Prince William and Henry’, the third and fourth sons of Frederick, then only sixteen and fourteen years old.

The largest of Wicke’s productions for one client to have survived intact would seem to be the service of 1745-47 made for James Fitzgerald, Viscount Leinster, subsequently Duke of Leinster, on his marriage to Emilia, daughter of the 2nd Duke of Richmond. This numbers some one hundred and seventy pieces, including an arbour epergne (Collection Walter Chrysler Jr., Parke-Benet, New York, 1960).

Other outstanding pieces are the ewer and dish of 1735 formerly in the collection (Jackson, History of English Plate), a group of gilt dishes made for Frederick, Prince of Wales, 1739 now dispersed (Sterling Clark Institute, Williamstown, Mass., the late Sir Philip Sassoon and others), and a pair of candelabra with nymph and faun figures of 1744 made for the Earl of Kildare (Christie’s 1926).

There is little doubt that from 1735 onwards Wickes’ clientele was as large and important as (if not possibly more so than) Lamerie’s and the quality of his productions, whoever the executants, in no way inferior to the latter’s.

You May Also Like