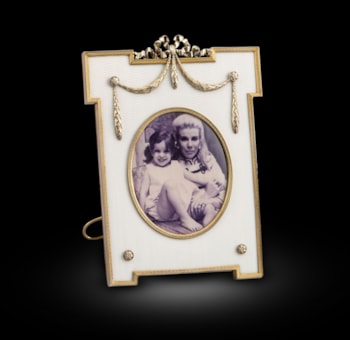

This pair of tureens on pedestal feet decorated with a chased band of bluebells mounted with a similarly decorated band of cast bluebells to the main body. The bodies with cast and applied swags, garlands, and roundels. The top rim with Vitruvian scrolls. The sweeping handles decorated with elegant bead. The covers with similar bead and acanthus décor. The finials formed as artichokes.

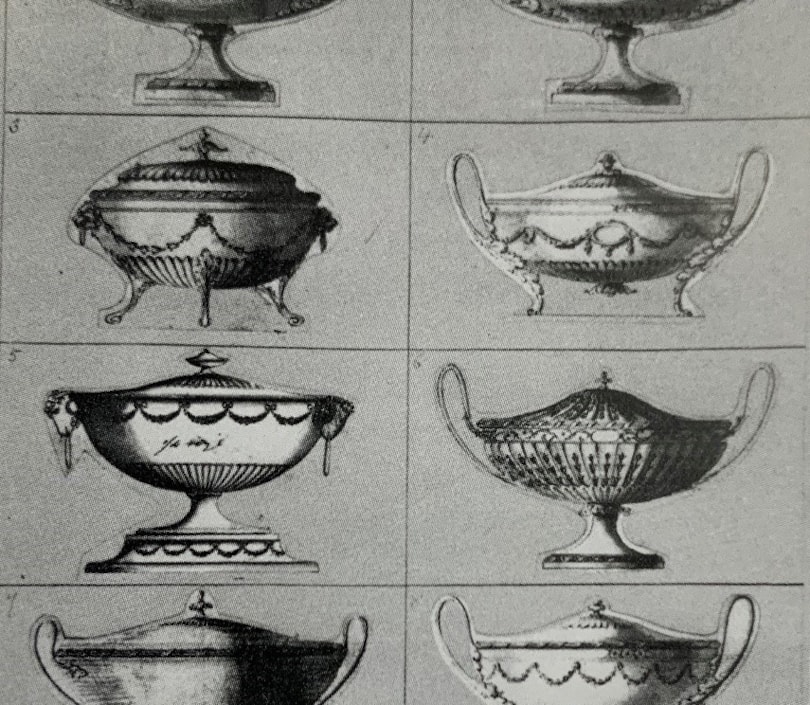

The designs directly attributable to Wyatt show how well he understood the classical repertory. His trademark slender jug form, with or without his characteristic splayed tripod stand, remains one of the icons of English neo-classicism. Even his weightier design for a jug was ultimately produced by the firm as an object of assured delicacy and makes it easy to understand Horace Walpole’s assertion about Wyatt, that he used the antique with more taste than Adam.

Unfortunately, as Wyatt's architectural practice grew and he turned more to ancient Greece for his inspiration, he seems to have had no more time, or patience, for designing silver. For Boulton & Fothergill, producing bespoke silverware of sophisticated neo-classical design was barely practical for a factory that was becoming increasingly mechanized. The whims of individual clients could not be catered for, and at the cutting edge of taste, styles often moved far too fast for mechanization to respond. Like any business, the Soho Manufactory, and its competitors in London such as the Bateman factory, had to grow, and to do so had to increase its consumer base. Inevitably, new custom was to come not from the aristocracy but from the burgeoning middle classes who wanted simple, practical design at reasonable cost, whether it was in silver or Sheffield Plate. Plain silver had never been out of fashion but Boulton's well-proportioned wares, with plain surfaces that were easy to keep clean and lent themselves well to mass production, were to be his most enduring legacy to the silver trade.

With this very much in mind, these sauce tureens fall into that rare group of hand-crafted unique commissions in those early days of Birmingham workshops 1773-1780. These tureens are an incredibly rare group of silver to have survived and the proportions, elegance and understanding of neo-classical repertoire can be clearly seen.

Drawings of soup tureens based on designs by James Wyatt (1746-1813), from Boulton & Fothegill Patter Book no.1 Birmingham Archives and Heritage, MS 3782/21/2.

The Silver and Decorative Arts Historian Kenneth Quickenden is currently working on a research project on the Boulton and Fothergill workshop. He believes the tureens to have been made for William Barrow, Manchester, who belonged to Thomas and William Barrow & Marriot & Co, fustian [a twilled cotton cloth, usually dyed dark] and smallware manufacturer.

The tureens were traced in the Day Book 1779-81, page 419, of the Matthew Boulton Papers in Birmingham Central Library as part of a large order placed by William Barrow. His order comprised 4 sauce tureens, 4 stands, 4 sauce ladles, 1 Cheese plate, 1 sugar basin. The total order came to £68 10s 6d. and was sent to him about 6 September. The 4 sauce tureens weighed 79 ozs 12 dwts 0grs and fashioning was charged at 5s 0d per oz. coming to £19 18s 0d.

William had a son, Thomas, also a businessman, who bought three pairs of candlesticks, and 2 snuffer pans also in silver, also in 1780.

At Soho House in Staffordshire, Boulton and Fothergill invested in the most advanced metalworking equipment, and the complex was admired as a modern industrial marvel. Although the cost of the principal building alone had been estimated at £2,000 (about £276,000 today); the final cost was five times that amount. The partnership spent over £20,000 in building and equipping the premises. After petitioning for a new assay office in Birmingham, parliament granted this in 1773. Using great designers of their day such as James Wyatt, Boulton & Fothergill produced wonderful silver in the neo-classical design and their hallmark is found on pieces assayed in those first few years after Birmingham started.

You May Also Like