Alexander Hamilton, 10th Duke of Hamilton, 7th Duke of Brandon KG PC FRS FSA (3 October 1767 – 18 August 1852), styled as the Earl of Angus until 1799 and Marquess of Douglas and Clydesdale from 1799–1819, was a Scottish politician and art collector.

Born on 3 October 1767 at St. James's Square, London, the eldest son of Archibald Hamilton, 9th Duke of Hamilton, he was educated at Harrow School and at Christ Church, Oxford, where he matriculated on 4 March 1786. He received his MA on 18 February 1789.

Hamilton was a Whig, and his political career began in 1802, when he became MP for Lancaster. He remained in the House of Commons until 1806, when he was appointed to the Privy Council, and Ambassador to the court of St. Petersburg until 1807; additionally, he was Lord Lieutenant of Lanarkshire from 1802 to 1852. He received the numerous titles at his father's death in 1819. He was Lord High Steward at King William IV's coronation in 1831 and Queen Victoria's coronation in 1838 and remains the last person to have undertaken this duty twice. He became a Knight of the Garter in 1836. He held the office of Grand Master Mason of the Freemasons of Scotland between 1820 and 1822. He held the office of President of the Highland and Agricultural Society of Scotland between 1827 and 1831. He held the office of Trustee of the British Museum between 1834 and 1852.

Alexander Hamilton at age 15, in a painting by Joshua Reynolds.

He married Susan Euphemia Beckford, daughter of William Thomas Beckford[3] and Lady Margaret Gordon, daughter of Charles Gordon, 4th Earl of Aboyne, on 26 April 1810 in London, England.

Hamilton was a well-known dandy of his day. An obituary notice states that "timidity and variableness of temperament prevented his rendering much service to, or being much relied on by his party ... With a great predisposition to over-estimate the importance of ancient birth ... he well deserved to be considered the proudest man in England." He also supported Napoleon and commissioned the painting The Emperor Napoleon in His Study at the Tuileries by Jacques-Louis David.

Lord Lamington, in The Days of the Dandies, wrote of him that 'never was such a magnifico as the 10th Duke, the Ambassador to the Empress Catherine; when I knew him he was very old, but held himself straight as any grenadier. He was always dressed in a military laced undress coat, tights and Hessian boots, &c'. Lady Stafford in letters to her son mentioned 'his great Coat, long Queue, and Fingers cover'd with gold Rings', and his foreign appearance. According to another obituary, this time in Gentleman's Magazine, he had 'an intense family pride'.

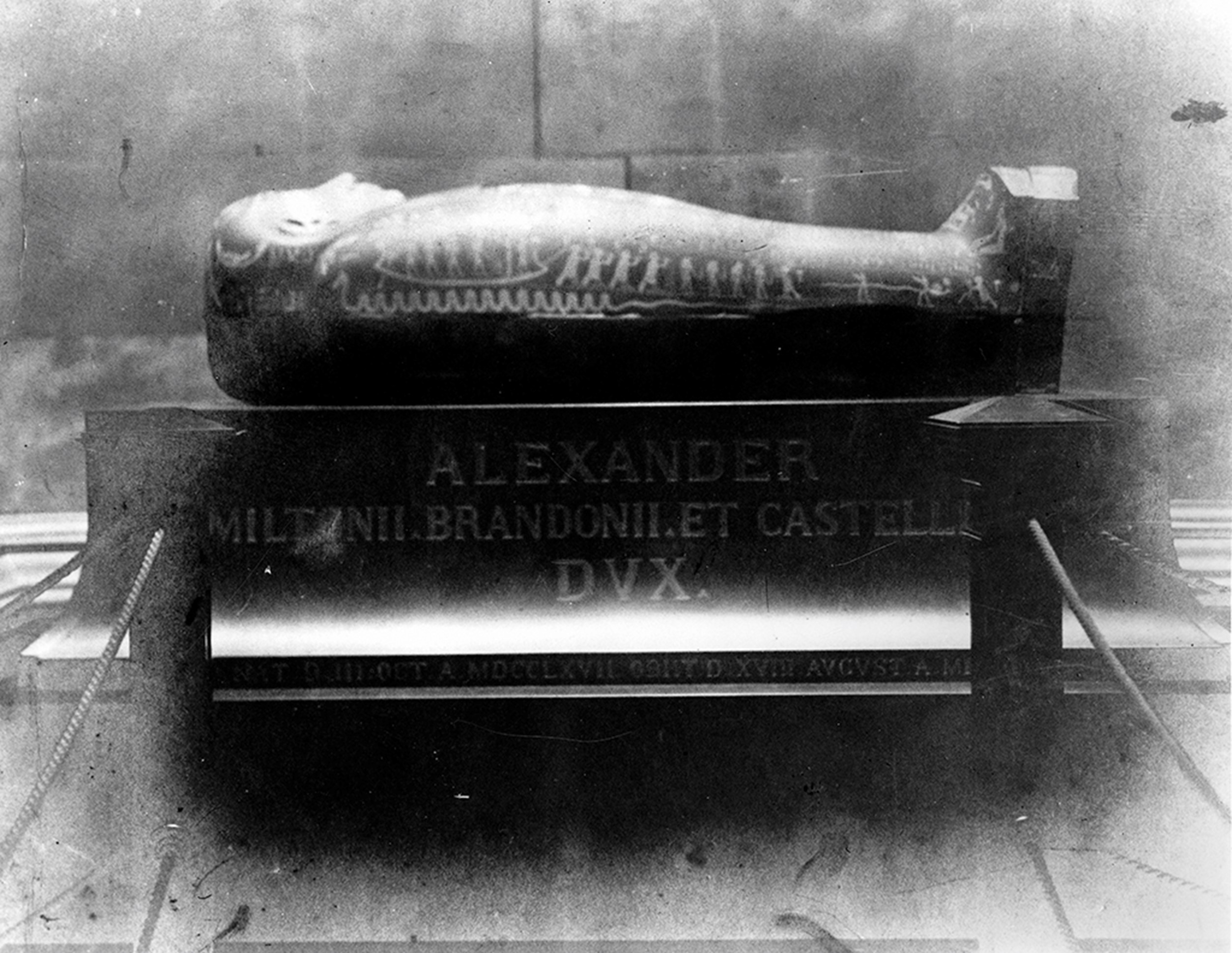

Hamilton had a strong interest in Ancient Egyptian mummies and was so impressed with the work of mummy expert Thomas Pettigrew that he arranged for Pettigrew to mummify him after his death. He died on 18 August 1852 at age 84 at 12 Portman Square, London, England and was buried on 4 September 1852 at Hamilton Palace, Hamilton, Scotland. In accordance with his wishes, Hamilton's body was mummified after his death and placed in a sarcophagus of the Ptolemaic period that he had originally acquired in Paris in 1836 ostensibly for the British Museum. At the same time, he had acquired the sarcophagus of Pabasa, an important nobleman which is now in the Kelvingrove Museum. In 1842 Hamilton had begun construction of the Hamilton Mausoleum as repository for the overcrowded family vault at the Palace. He was interred there with other Dukes of Hamilton, from the 1858 completion of the Mausoleum until 1921 when subsidence and the subsequent demolition of the Palace forced removal of the bodies to the Bent cemetery in Hamilton, where he still lies buried in his sarcophagus.

His collection of paintings, objects, books and manuscripts was sold for £397,562 in July 1882. The manuscripts were purchased by the German government for £80,000. Some were repurchased by the British government and are now in the British Museum.

Hamilton Palace

The demolition of Hamilton Palace at Hamilton in South Lanarkshire in the 1920s and the dispersal of its treasures in two sales in 1882 and 1919 was a national tragedy.

It was the grandest country house in Scotland and was filled with outstanding furniture and art, thanks to Alexander, 10th Duke of Hamilton (1767-1852). The sales attracted worldwide interest; the 1882 sale raised nearly £400,000, a colossal sum at the time, and saw the 10th Duke’s prized collection scattered across the globe.

Items from Hamilton Palace have been added to National Museums Scotland’s collection over the last 40 years, including part of a silver-gilt tea service owned by the Emperor Napoleon to a section of a drawing room wall from the palace, they illustrate the prolific collecting of an extraordinary man driven by an intense desire to demonstrate his wealth, status and power.

The Marble Hall on the first floor, showing three of the five bronze statues associated with King Francis I of France

Alexander, 10th Duke of Hamilton, was immensely proud of his family’s status. As a consequence of the marriage of the 1st Lord Hamilton to a daughter of King James II in the 15th century, the Duke’s ancestor, the 2nd Earl of Arran, was heir presumptive to the throne of Scotland and Regent of Scotland during the minority of Mary, Queen of Scots. King Charles I awarded the dukedom of Hamilton to his relatives in 1643, and both the 1st Duke and his brother, the 2nd Duke, went on to die for the Stuart cause during the Civil War. In 1711, Queen Anne granted a second dukedom, that of Brandon, to the 4th Duke of Hamilton.

Alexander was 10th Duke of Hamilton, 7th Duke of Brandon and the premier peer of Scotland. He also claimed the French dukedom of Châtelherault, which had been awarded to the 2nd Earl of Arran by King Henry II of France in 1548-49, and viewed himself as the legitimate heir to the throne of Scotland, following the death of Cardinal Henry, Duke of York, the last of the male Stuart line, in 1807.

Between 1824 and 1831, the 10th Duke built a huge, north-facing addition onto the back of the small, south-facing baroque palace, which had been constructed in the 1690s. The Duke filled the palace with furniture and art, and created the Scottish equivalent of the British Royal Collection.

Many of these items were chosen to emphasise the Duke’s own exalted status by associating him with emperors, kings and queens.

Thus, visitors to Hamilton Palace climbed a great ceremonial staircase watched by black basalt busts of emperors and ran the gauntlet past five life-size bronze copies of Classical statues, which were believed to have been made for King Francis I of France.

They then found themselves in a large room with a substantial marble bust of the Emperor Napoleon I and Italian Old Master paintings.

The Egyptian sarcophagus containing the 10th Duke of Hamilton

Later rooms contained dozens of examples of French 18th-century furniture, including some of British ambassador in St Petersburg, the Duke bought an exceptionally large Byzantine sardonyx bowl, in the belief that it was the holy water stoup of the Emperor Charlemagne, the founder of the Holy Roman Empire.

Back in London in 1812, he paid more than £240 for an enamelled gold stand from a gold monstrance that the Emperor Philip II of Spain had presented to the royal monastery of the Escorial, outside Madrid.

The 10th Duke united the two parts to form an astonishing imperial relic. It was the most highly valued object in his collection and an annotation in the 1852-53 palace inventory reveals that it was intended to serve as the baptismal font of the House of Hamilton.

The 10th Duke admired Napoleon as the saviour of the French Revolution and commissioned a portrait of him from his own official painter, Jacques-Louis David, in 1811. After the Emperor’s final defeat, the Duke went to live in Rome and became a close friend of Napoleon’s favourite sister, Princess Pauline Borghese.

The Hamilton Mausoleum, built by the 10th Duke of Hamilton, is all that visibly remains of the Hamilton Palace Estate

On her death in 1825, Princess Pauline bequeathed her travelling service – containing dozens of exquisite gold, silver-gilt, glass and ivory items – to the Duke. The gift inspired him to commission Napoleon’s architect Charles Percier to design interiors for Hamilton Palace and to purchase the silver-gilt ‘tea service’ which had been supplied in connection with the Emperor’s marriage to the Archduchess Marie-Louise of Austria in 1810 from King Charles X of France in 1830.

They reflect the character and interests of an extraordinary man, who, due to his belief in his own importance and his interest as a Freemason in ancient Egypt, would elect to be mummified and buried in an ancient Egyptian sarcophagus, inside a new mausoleum in the grounds of Hamilton Palace, in 1852 (now one of the town’s most famous buildings).

Son of Thomas Storr of Westminster, first silver-chaser later innkeeper, born 1771. Apprenticed c'1785. Before his first partnership with William Frisbee in 1792 he worked at Church Street, Soho, which was the address of Andrew Fogelberg. This is also the address at which Storr's first separate mark is also entered. First mark entered as plateworker, in partnership with William Frisbee, 2 May 1792. Address: 5 Cock Lane, Snow Hill. Second mark alone, 12 January 1793. Address: 30 Church Street, Soho. Third mark, 27 April 1793. Fourth 8 August 1794. Moved to 20 Air Street, 8 October 1796, (where Thomas Pitts had worked till 1793). Fifth mark, 29 November 1799. Sixth, 21 August 1807. Address 53 Dean Street, Soho. Seventh, 10 February 1808. Ninth, 21 October 1813. Tenth, 12 September 1817. Moved to Harrison Street, Gray's Inn Road, 4 March 1819, after severing his connection with Rundell, Bridge and Rundell. Eleventh mark, 2 September 1883. Address: 17 Harrison Street. Twelfth and last mark, 2 September 1833. Heal records him in partnership with Frisbee and alone at Cock Lane in 1792, and at the other addresses and dates above, except Harrison Street. Storr married in 1801, Elizabeth Susanna Beyer of the Saxon family of piano and organ builders of Compton Street, by whom he had ten children. He retired in 1838, to live in Hill House in Tooting. He died 18 March 1844 and is buried in Tooting Churchyard. His will, proved 3 April 1844, shows an estate of £3000. A memorial to him in Otely Church, Suffolk was put up by his son Francis the then incumbent of the parish. For full details of Storr's relationship with Rundell, Bridge and Rundell please see N.M. Penzer, 1954 or Royal Goldsmiths, The Art of Rundell and Bridge, 2005.

Storr's reputation rests on his mastery of the grandoise neo-Classical style developed in the Regency period. His early pieces up to about 1800 show restrained taste, although by 1797 he had produced the remarkable gold font for the Duke of Portland. Here, however the modelling of the classical figures must presumably have been the work of a professional sculptor, as yet unidentified, and many of the pieces produced by him for Rundell and Bridge in the Royal Collection must have sprung from designs commissioned by that firm rather than from his own invention. On the other hand, they still existed in his Harrison Street workshop, until destroyed in World War II, a group of Piranesi engravings of classical vases and monuments bearing his signature, presumably used as source material for designs. The massiveness of the best of his compositions is well shown in the fine urn of 1800 at Woborn Abbey, but the Theocritus Cup in the Royal Collection must be essentially ascribed to the restraint of its designer John Flaxman, while not denying to Storr its superb execution. Lord Spencer's ice pails of 1817 show similar quality. Not all Storr's work however was of classical inspiration. The candelabra of 1807 at Woburn derive from candlesticks by Paul Crespin of the George II period, formerly part of the Bedford Collection, and he attempted essays in floral rococo design from time to time, which tend to over-floridity. On occasions the excellence of his technical qualities was marred by a lack of good proportions, as in the chalices of the church plate of St Pancras, 1821. In spite of these small lapses there is no doubt that Storr rose to the demands made upon him as the author of more fine display plate than any other English goldsmith, including Paul De Lamerie, was ever called upon to produce.

You May Also Like